Agents as Distributed Systems: outbox, sagas, and “eventually correct” workflows

Agents don’t “run in a loop” — they run across networks, vendors, and failures. This month is about the three patterns that make agent workflows survivable: durable intent (outbox), long-running transactions (sagas), and reconciliation (“eventually correct”).

Axel Domingues

Agents are finally useful in production… and immediately annoying.

Not because the model is “wrong”.

Because the agent is a distributed system the moment it touches anything real:

- a payments API

- a CRM

- a Git repo

- a browser UI

- an internal microservice

- an email provider

- a human approval step

- a rate limit

- a timeout

- a retry

So in June, I’m reframing the mental model:

If your agent performs actions, you are operating a distributed workflow engine — whether you intended to or not.

And distributed workflows have one job:

make reality converge.

Not instantly. Not perfectly.

But eventually — and provably.

This is where “eventual consistency” becomes too vague to be useful.

I prefer a more demanding phrase:

eventually correct.

Meaning:

- you know what “correct” means (invariants)

- you know how to get back to “correct” (retries + reconciliation)

- you can prove (with logs + state) why you’re correct

It’s about the part that hurts after planning: durable execution across failures.

Treat every action as a transaction

Define invariants first, then build workflows that can’t violate them.

Durable intent (Transactional Outbox)

Write “what must happen” to your DB before you try to make it happen.

Long-running workflows (Sagas)

Split work into retryable steps with timeouts, compensation, and checkpoints.

Reality convergence (Reconciliation)

Assume some steps fail silently and build repair loops that detect + fix drift.

Why agents become distributed systems instantly

In a normal request/response app, failure is annoying but bounded:

- client retries

- server logs

- database rollbacks

In an agentic app, failure is the baseline state.

Because agent workflows:

- are long running

- cross trust boundaries

- call multiple vendors

- may have human approval gaps

- may include “computer use” actions (UI automation)

- are retried automatically by queues/schedulers

- can be restarted after deploys or crashes

That combination forces you into a small set of patterns that survive the real world.

They all start with the same question:

What must never be wrong?

Step 0: define invariants (what must never be wrong)

“Invariant” sounds academic. In practice it’s simple:

identify the things you can’t undo cheaply.

Some examples from agent systems:

- no double charge (payments)

- no duplicate external side effects (tickets, emails, purchases)

- no privilege escalation (permissions, approvals)

- no irreversible action without explicit intent (delete data, publish, deploy)

- no cross-tenant data leak (multi-tenant products)

- no silent drift (the agent thinks it published, but it didn’t)

dashboards that look great while the system violates the only thing that matters.

A useful rule:

- keep invariants strongly consistent (single writer, transactional state)

- allow everything else to become eventually correct via workflows + reconciliation

The three building blocks

You can ship a surprising amount of agent capability with three patterns:

- Transactional Outbox — durable intent + reliable publishing

- Sagas — long-running state machines with compensation

- Reconciliation loops — periodic repair that enforces invariants

Let’s make each one concrete.

1) Transactional Outbox: “write intent before you do work”

The most common agent failure mode in production is painfully mundane:

The agent changes local state… then fails to trigger the next step.

Or worse:

The agent triggers the next step… then fails before persisting local state.

Both lead to ghosts:

- missing work

- duplicated work

- “we don’t know what happened” incidents

The Transactional Outbox fixes this by making a strict deal:

In a single DB transaction, write:

- the state change, and

- a durable “intent event” describing the side effect to perform.

Then a separate worker publishes/drives those intents.

The minimal outbox schema

You can start with a tiny table:

-- Outbox is not an “event stream”. It’s a durable todo list.

create table outbox (

id uuid primary key,

type text not null, -- e.g. "GenerateImageRequested"

key text not null, -- idempotency key / correlation id

payload jsonb not null,

status text not null, -- "pending" | "sent" | "failed"

attempts int not null default 0,

next_attempt_at timestamptz not null default now(),

created_at timestamptz not null default now(),

updated_at timestamptz not null default now()

);

create unique index outbox_unique_key on outbox(type, key);

A few notes that matter in real life:

keyis not optional. It’s how you dedupe at-least-once delivery.next_attempt_atmakes backoff explicit (and queryable).- unique constraint forces idempotency at the DB boundary.

The outbox write: one DB transaction

Example: “create job + emit event”

begin;

insert into jobs (id, state, ...) values (:job_id, 'queued', ...);

insert into outbox (id, type, key, payload, status)

values (:outbox_id, 'JobQueued', :job_id, :payload_json, 'pending');

commit;

Now you’ve made the system robust against:

- process crashes

- queue outages

- transient vendor failures

Because the intent is durable.

2) The dispatcher: turning durable intent into execution

An outbox is only useful if something drains it.

That “something” is usually boring — and that’s a compliment.

Dispatcher responsibilities

Scan + lock

Select a small batch of pending outbox rows and lock them to avoid double dispatch.

Enqueue work

Create queue messages / cloud tasks that trigger workers (at-least-once).

Advance state

Mark “sent” only after enqueue succeeds. Track attempts + next retry time.

Observe everything

Emit metrics for lag, attempts, failure rate, and oldest pending item.

The two delivery truths you must accept

Truth #1: delivery will be at-least-once.

Your queue will retry. Your dispatcher will retry. Your worker will retry.

So you must build idempotency.

Truth #2: ordering is not guaranteed.

If ordering matters, encode it in your workflow state machine — not in the queue.

3) Sagas: long-running workflows that can fail safely

Agents don’t do “one call”. They do sequences:

- plan → retrieve → decide → act → verify → report

- generate → review → publish → distribute → monitor

- validate → propose → get approval → execute → confirm

That’s a workflow.

And workflows are distributed transactions with time gaps.

A saga is just the honest framing:

a durable state machine where each step is retryable and some steps have compensation.

Orchestration vs choreography

A central workflow record advances through states:

- easy to reason about

- easy to time out and alert

- easy to pause for humans

- easy to audit

Agent platforms almost always want orchestration because it’s debuggable.

Services react to events and emit new events.

- scales nicely when boundaries are stable

- becomes confusing when workflows change often

- makes “what happened?” investigations harder

Choreography can work, but agent product iteration usually benefits from a central ledger.

A concrete saga: “publish an AI-generated blog post”

Let’s map a realistic workflow (that crosses vendors):

- Generate draft (LLM)

- Generate cover image (image model)

- Run policy checks + brand checks

- Publish to CMS

- Announce on social / email

- Verify publication + links resolve

Every step can fail.

So your saga record might look like:

Workflow: PublishArticle

State: DRAFT_GENERATED -> IMAGE_GENERATED -> CHECKED -> PUBLISHED -> ANNOUNCED -> VERIFIED

And each transition is driven by a job/worker, not by a single process “waiting”.

- you will know what state you are in

- you will know what to do next

- and you can resume after failure without guessing

The “eventually correct” contract (and why it matters)

“Eventually consistent” is too vague to operate.

Eventually correct means you can answer these questions at 3am:

- What is the current state of the workflow?

- Which side effects have happened?

- Which ones have not?

- What is safe to retry?

- What must be compensated?

- How do we prove we didn’t violate invariants?

To get there, you need a small set of non-negotiables.

Idempotency keys everywhere

Every external side effect must be repeatable without duplication.

Durable state machine

Workflow state lives in the DB, not in memory.

Explicit timeouts + DLQs

Don’t “retry forever” silently. Escalate stuck work.

Safe replay + backfills

You should be able to re-run steps without fear.

Compensation: when “undo” is possible (and when it isn’t)

Compensation is the scary part of sagas because it forces honesty.

Some actions are reversible:

- delete a draft

- cancel a pending ticket

- revoke an access token

- refund a payment (sometimes)

Some actions are not:

- sending an email (you can send a follow-up, but you can’t unsend)

- publishing to a social feed

- deleting user data (you should not “compensate” by restoring)

So compensation is less about “undo” and more about:

if we can’t undo, we must prevent the action until intent is explicit and audited.

This is where governance controls actually become architecture.

Make it:

- explicit (human approval, or strong policy gate)

- logged (who/what/why)

- reversible where possible (soft deletes, staging)

Human-in-the-loop is a first-class workflow state

Most agent systems ship a fantasy first:

“fully autonomous agent”

Then reality arrives:

- compliance asks for audit trails

- customers ask for approvals

- security asks for least privilege

- operations asks for kill switches

The good news: sagas make humans easy.

Add states like:

AWAITING_APPROVALNEEDS_INPUTREJECTEDESCALATED

And treat “human decisions” as another event that advances the state machine.

Reconciliation: the repair loop that makes “eventually correct” true

Even with outbox + sagas, drift still happens:

- vendor returns 200 but didn’t do the thing

- webhooks drop

- UI automation “clicked” the wrong element

- a worker deployed mid-step

- rate limits cause partial completion

- external state changes out of band

Reconciliation is the system admitting that:

success signals are fallible, so we periodically verify reality and repair it.

What reconciliation does

- detects workflows stuck too long in a state

- cross-checks external systems (CMS status, payment status, email send logs)

- re-enqueues safe retries

- escalates unsafe cases to humans

- records a repair action (audit trail)

The core principle

Reconciliation must be safe:

- never violate invariants

- never apply irreversible actions

- never “guess” — verify first

You’ll just do it manually, under pressure, at the worst possible time.

A practical implementation blueprint

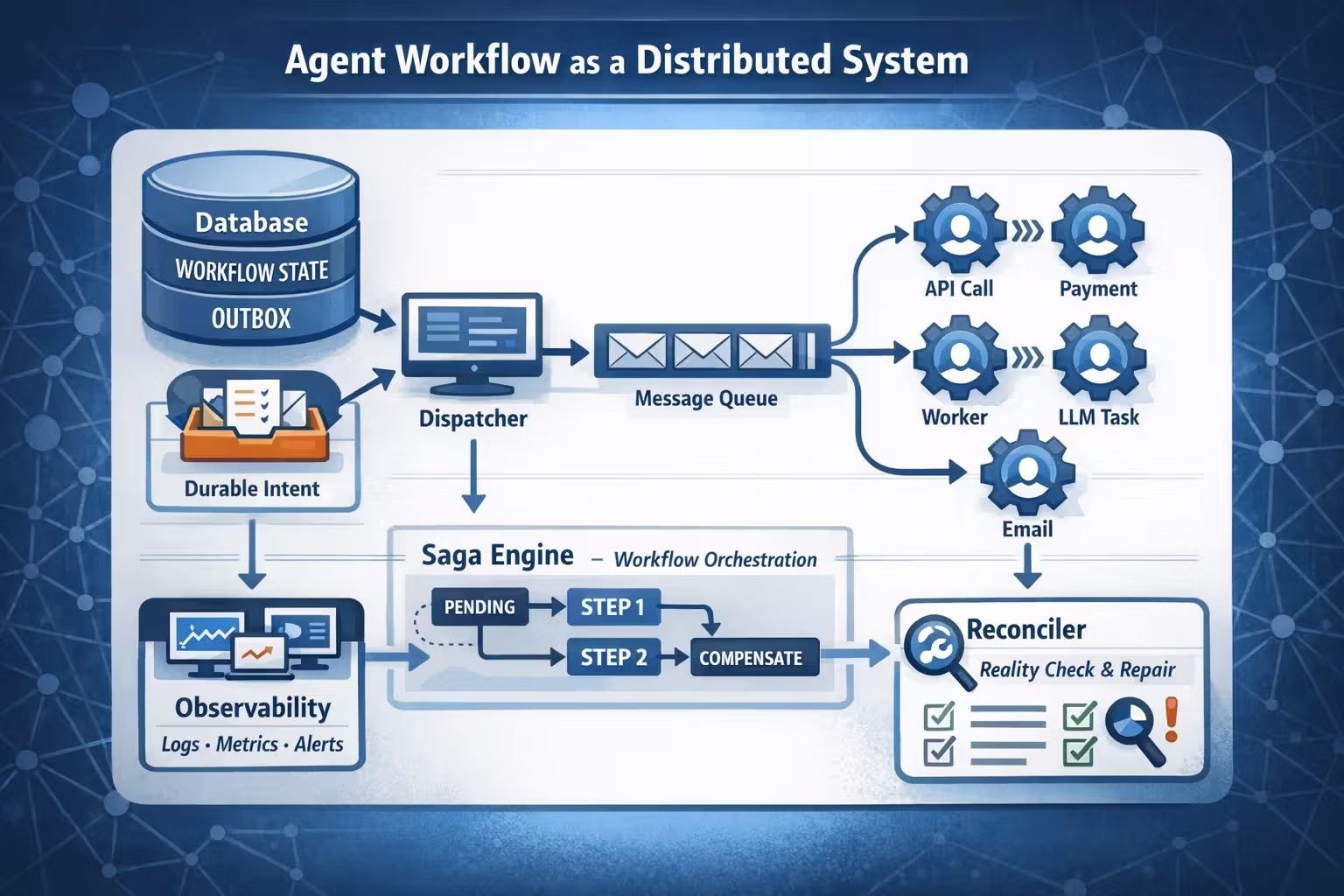

This is the architecture I keep seeing converge across “agent platforms”:

- DB holds workflow state + outbox (source of truth)

- Dispatcher drains outbox into a queue

- Workers execute single steps (retryable, idempotent)

- Saga engine advances the workflow state machine

- Reconciler periodically checks and repairs drift

- Observability ties it together with traces + logs + metrics

If you squint, this is “classic distributed systems”… with a model in the loop.

Build it in 7 steps

Choose a workflow record as your source of truth

Create a workflows table with:

type,id,statecontext(json)updated_at,deadline_atowner(agent, system, human)correlation_id

Make every step a job (single responsibility)

A job does one thing:

- call one external system (or one tool family)

- update state

- emit outbox events for the next step

Add an outbox table with unique keys

Enforce idempotency at the database boundary:

- unique

(type, key) - explicit

attemptsandnext_attempt_at

Write state + outbox in one transaction

Never publish “intent” without persisting the state change that justifies it.

Drain outbox into a queue (at-least-once)

Keep the dispatcher boring:

- small batches

- locks

- retries with backoff

- metrics for lag

Implement reconciliation as a scheduled workflow

Reconciliation should:

- find stuck workflows

- verify external reality

- re-enqueue safe work

- escalate unsafe cases

Add kill switches and safe modes early

You will need:

- pause all workflows

- pause a specific workflow type

- disable a risky step (e.g. publish)

- switch to “approval required” mode

Failure modes you should expect (and design for)

Cause: missing idempotency keys, or dedupe not enforced at DB boundary.

Fix: unique keys + idempotent external requests + “already done” handling in workers.

Cause: retries without deadlines, missing reconciliation, no DLQ/alerting.

Fix: explicit deadlines, DLQs, and a reconciler that escalates.

Cause: state lives in logs, not in a durable state machine.

Fix: workflow record as source of truth + trace correlation ids.

Cause: assuming success responses are truth.

Fix: reconciliation that verifies external reality and repairs.

Cause: no safe replay, no backfills, no invariant-first thinking.

Fix: design replayability and add a “repair job” toolkit.

The mental model I want you to keep

Agents are not “a loop with tool calls”.

Agents are workflows across boundaries.

So ship them like workflows:

- durable intent (outbox)

- durable progress (saga state machine)

- durable truth (reconciliation + invariants)

- durable control (kill switches + approvals)

That’s how you stop building demos and start building platforms.

June takeaway

Eventual consistency is a property you hope for.

Eventually correct is a property you design, audit, and repair toward.

Resources

Distributed Data: Transactions, Outbox, Sagas, and ‘Eventually Correct’

My 2022 deep dive on the exact reliability patterns this month builds on.

“Designing Data-Intensive Applications” (Kleppmann)

The clearest mental model for distributed systems tradeoffs and correctness.

What’s next

Next month: Multi-Agent Systems Without Chaos: supervisors, specialists, and coordination contracts.

Because once you can run a single agent workflow reliably… you’ll want to run many.

And that’s where coordination becomes architecture.

Multi-Agent Systems Without Chaos: supervisors, specialists, and coordination contracts

Multi-agent setups don’t fail because “agents are dumb.” They fail because we forgot distributed-systems basics: authority, contracts, budgets, and observability. This month is a practical architecture for scaling agents without scaling chaos.

The 1M-Token Era: how long context changes retrieval economics and system design

Long context doesn’t kill RAG — it changes what’s cheap, what’s risky, and what needs architecture. This month is a practical guide to building “context-first” systems without shipping a cost bomb (or a data leak).