Multi-Agent Systems Without Chaos: supervisors, specialists, and coordination contracts

Multi-agent setups don’t fail because “agents are dumb.” They fail because we forgot distributed-systems basics: authority, contracts, budgets, and observability. This month is a practical architecture for scaling agents without scaling chaos.

Axel Domingues

In June, I argued that agents are distributed systems in disguise.

If your agent triggers retries, fan-outs, tool calls, and side effects, you’re already living in the world of:

- idempotency

- ordering

- timeouts

- and “eventually correct” state machines

Now July makes it sharper:

Multiple agents is not “more intelligence.”

It’s more concurrency, more handoffs, and more failure modes.

And if you don’t design for that, the system doesn’t become smarter.

It becomes louder.

It’s how to build a multi-agent system you can:

- operate

- debug

- and defend in a design review

The real goal

Scale capability by adding specialists without scaling chaos.

The big mistake

Treating multi-agent like a vibe, not like a coordination problem.

The core pattern

A supervisor owns decisions. Specialists execute bounded work.

The missing piece

Coordination contracts: schemas, budgets, authority, and stop conditions.

Why Multi-Agent Systems Fail in Practice

Most multi-agent failures look like “the model is unreliable.”

But the real causes are architectural:

- Role soup: every agent can do everything, so nobody is accountable for outcomes.

- No authority: agents argue, loop, or overwrite each other’s decisions.

- No contracts: handoffs are prose; downstream assumptions are implicit.

- Unbounded work: agents keep trying (or keep calling tools) because nothing tells them to stop.

- Invisible state: you can’t answer “why did it do that?” without reading 4000 tokens of logs.

They generate a lot of text, a lot of tool calls, and a lot of activity.

That’s not progress.

That’s heat.

So we need a discipline that looks boring on purpose:

control plane + contracts + observability.

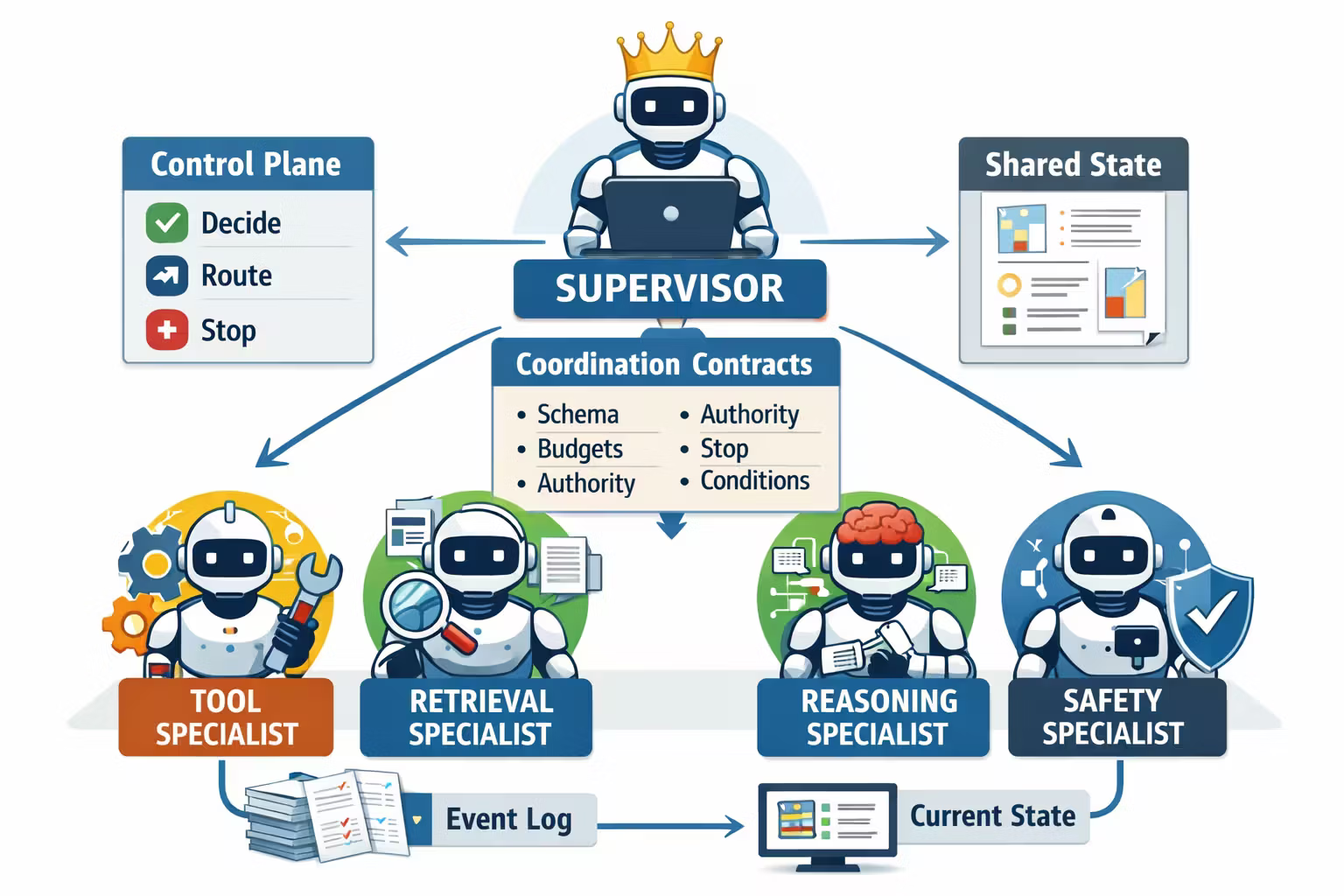

The Architecture: One Control Plane, Many Workers

The simplest mental model is:

- Supervisor = control plane (decides, routes, stops)

- Specialists = workers (execute bounded tasks)

- Contracts = the protocol (what gets passed, what’s allowed, what “done” means)

This is not about “hierarchy” as a philosophy.

It’s about having an authority you can point to when something goes wrong.

The Supervisor Pattern

A good supervisor does four jobs and refuses the rest.

1) Decompose

Turn a user goal into bounded tasks with explicit success criteria.

2) Route

Pick the right specialist based on the task type and constraints.

3) Budget + stop

Enforce time/token/tool budgets, detect loops, and stop cleanly.

4) Commit

Decide what becomes system state vs what is discarded.

Supervisor does not mean “one agent to rule them all”

The supervisor is not the smartest model in the room.

It’s the most responsible component in the room.

If you want a clean principle:

- what happens next

- what tools are allowed

- when we stop

- and what becomes truth

That’s enough to make debugging possible.

Specialists: Make Them Narrow on Purpose

Specialists should be boring.

Not because capability is bad, but because:

In multi-agent systems, generality multiplies ambiguity.

A specialist should have:

- a narrow purpose

- a constrained toolset

- a stable I/O schema

- and an evaluation suite you can run in CI

Here’s a practical specialist taxonomy.

Tool specialist

One toolchain, one domain. Example: “calendar ops”, “CRM update”, “invoice creation”.

Retrieval specialist

Owns the knowledge boundary: query planning, citations, and grounding decisions.

Reasoning specialist

Planning, constraint solving, tradeoff analysis. No side effects.

Safety specialist

Policy checks, PII handling, risky-action gating, and audit logging.

An agent runtime isn’t just an SDK.

It’s an execution substrate where you can actually enforce tool scopes, budgets, and tracing.

Coordination Contracts: The Thing That Makes Multi-Agent Work

Coordination contracts are the missing layer.

They turn “agents talking” into “components cooperating.”

A contract should answer six questions.

Input schema

What fields are required? What is optional? What are valid ranges?

Output schema

What does “done” look like? What is the result shape?

Authority

Can this specialist commit state, or only propose?

Allowed tools

Which connectors are permitted, with what scopes?

Budgets

Token cap, tool-call cap, wall-clock timeout, and retry policy.

Stop conditions

When must the specialist halt, escalate, or ask for confirmation?

“Contract” does not mean “legal document”

It means a protocol.

In practice, contracts become:

- JSON schema / Zod / Pydantic models

- enum-based action spaces

- structured tool outputs

- typed error codes (

NEEDS_INPUT,POLICY_BLOCKED,TOOL_DOWN,LOW_CONFIDENCE)

If you only take one idea from this post:

You have improv.

Shared State Without Shared Confusion

Multi-agent systems need shared context.

But “everyone reads and writes a giant blob” is how you get chaos.

Use shared truth, not shared memory.

A practical approach is a blackboard with strict rules:

- specialists can append observations

- only the supervisor can commit facts into canonical state

- canonical state changes are versioned and auditable

Think of it as:

- event log (everything that happened)

- current state (the latest “truth” the system operates on)

This mirrors what we already do in distributed systems:

- write intent durably

- apply idempotent transitions

- reconcile when the world disagrees

Coordination Topologies That Actually Ship

Not every multi-agent system should be a swarm.

Here are the topologies that show up in production-like setups.

Use when: you want clarity and operability.

- supervisor decomposes and routes

- specialists execute bounded work

- supervisor commits results or requests more info

Use when: tasks are independent and can run concurrently.

- split into subtasks with identical output schema

- run specialists in parallel

- reduce into a single decision or merged artifact

Use when: you need robustness against a single model’s blind spots.

- one agent proposes

- one or more critique

- supervisor decides whether to revise or ship

Use when: you have many well-bounded skills.

- fast routing step selects a specialist

- specialist handles end-to-end within strict budgets

- supervisor is mainly for escalation paths

Add topologies only when you have evidence:

- latency constraints

- accuracy/robustness needs

- or a large catalogue of skills

The Failure Modes (And Their Fixes)

Multi-agent breakage is repetitive. Which is good news.

It means you can design guardrails.

Cause: no stop conditions, no budget enforcement

Fix: per-task budgets + explicit terminal states + loop detector (repeated actions / repeated tool errors)

Cause: shared state without authority

Fix: append-only observations + supervisor-only commits + versioned state

Cause: tools not constrained; authority unclear

Fix: tool allowlists per specialist + write scopes + human confirmation gates for high-impact actions

Cause: no evals across scenarios; no tail-latency planning

Fix: scenario harness + CI gating + SLOs (p95 latency, tool error rate, retry rate)

Cause: missing trace correlation and structured logs

Fix: trace IDs across agents/tools + structured events + replayable runs

Observability: Trace the Conversation Like a Workflow

If you can’t answer “why did it do that?” you don’t have observability.

You have log storage.

For multi-agent systems, you want:

- a trace per user request

- spans per agent step

- attached tool calls and tool responses

- token/time/cost metrics per span

- state transitions as structured events

The debugging unit

A single request should be replayable as a deterministic trace (inputs + tool outputs + decisions).

- offline replay

- what-if prompts

- regression triage (“this started failing after commit X”)

A Practical Build Recipe

Here’s how to go from “multi-agent demo” to “multi-agent system.”

Define specialist boundaries

Create 3–5 specialists with narrow scopes:

- one tool specialist

- one retrieval specialist

- one reasoning specialist

- one safety specialist (or policy gate)

Write down their I/O schemas first.

Implement coordination contracts

For each specialist:

- input schema

- output schema

- tool allowlist + scopes

- token/tool/time budgets

- stop conditions + escalation codes

Build the supervisor as a state machine

Supervisor logic should be explicit:

DECOMPOSE → DISPATCH → COLLECT → DECIDE → COMMIT → DONE- handle terminal states (

NEEDS_INPUT,POLICY_BLOCKED,FAILED_RETRYABLE)

Establish shared truth

Create:

- append-only event log

- canonical state snapshot (versioned)

- supervisor-only commit path

Add tracing from day one

Every agent step emits:

- trace ID

- span ID

- contract version

- budget consumption

- tool calls + outcomes

Create scenario evals before you scale

Write scenario tests that assert:

- correct routing to specialists

- no prohibited tool calls

- budgets respected

- stable outcomes across seeds

You’re scaling incident volume.

Resources

Erlang/OTP — Supervision Principles (supervisors & workers)

The original “supervisor owns restarts” pattern: clear authority, bounded responsibilities, and failure containment — exactly what your supervisor/specialist split is borrowing.

Temporal — Workflow Execution (durable orchestration)

A production-grade reference for coordination under retries/timeouts: durable state machines, idempotency, and replay — the practical substrate behind “agents are distributed systems.”

FAQ

No.

Single-agent systems are easier to operate and often “good enough.”

Go multi-agent when you need:

- distinct toolchains with different permissions

- parallel work with bounded subtasks

- or robustness via critique/verification loops

You can — and you should start there.

Multi-agent becomes valuable when you need:

- separate scopes (least privilege)

- separate eval suites

- and separate failure domains

Accountability.

When something goes wrong, you can answer:

- which decision was made

- by which component

- under which contract version

- with which budget constraints

Not if you design it as an execution component.

A supervisor is:

- a state machine

- a router

- a budget enforcer

- and a commit authority

The prompt is just one of its mechanisms.

What’s Next

Multi-agent systems multiply power — and risk.

The next month is the part most teams only learn after a breach:

Security for Agent Connectors: least privilege, injection resistance, and safe toolchains

Because once your agents can act…

security stops being a checklist.

It becomes architecture.

Security for Agent Connectors: least privilege, injection resistance, and safe toolchains

In 2025, the riskiest part of “agentic” systems isn’t the model — it’s the connectors. This month is a practical playbook for securing tools: least privilege, prompt-injection resistance, safe side effects, and auditability that holds up under incident response.

Agents as Distributed Systems: outbox, sagas, and “eventually correct” workflows

Agents don’t “run in a loop” — they run across networks, vendors, and failures. This month is about the three patterns that make agent workflows survivable: durable intent (outbox), long-running transactions (sagas), and reconciliation (“eventually correct”).