Distributed Data: Transactions, Outbox, Sagas, and “Eventually Correct”

Once your system crosses a process boundary, “a transaction” stops being a feature and becomes a strategy. This post is a practical mental model for distributed data: what to keep strongly consistent, what to make eventually consistent, and how to do it safely with outbox + sagas.

Axel Domingues

“Just wrap it in a transaction.”

That sentence works… right up until your system crosses a boundary you can’t BEGIN and COMMIT around:

- a second database

- a queue

- a third-party API

- a service owned by a different team

- a network that will partition at the worst moment

At that point, the problem isn’t distributed systems theory.

It’s product correctness under failure.

This month is about building the mental model and the practical toolkit for that reality:

- what “eventual consistency” actually means

- how to keep the important invariants strong

- how to make the rest eventually correct

- and how to implement it without creating ghosts, duplicates, or money-loss bugs

Not just patterns — a decision about what must never be wrong.Distributed data needs a truth design.

The one question that matters: “What must never be wrong?”

Distributed data is not a technology problem.

It’s an invariants problem.

An invariant is a statement your business can’t afford to violate, even briefly.

Examples:

- Payments: “Charge a customer at most once for an order.”

- Inventory: “Never sell more items than you actually have.”

- Security: “A revoked token can’t access protected resources.”

- Money movement: “Balances never go negative unless you explicitly allow it.”

Everything else is negotiable.

And that’s the core reframing:

The goal isn’t “strong consistency everywhere.”

The goal is “strong consistency where it matters, eventual consistency everywhere else.”

The trap

Modeling every update as “must be immediate + correct everywhere” pushes you into brittle distributed transactions.

The unlock

Define invariants, then design a flow where those invariants are protected by one authoritative writer.

Why distributed transactions feel “obvious”… and then hurt you

When teams first hit multi-service updates, they reach for the database instinct:

- “Can we do a transaction across services?”

- “Can we just use 2PC?”

- “Can the DB handle it?”

Sometimes, with very controlled infrastructure, you can.

But in most modern systems, distributed transactions are a poor default because they:

- couple availability across multiple systems

- amplify latency (the slowest participant is now your transaction time)

- create complex failure modes (timeouts, coordinator failover, partial locks)

- make operational incidents harder to reason about

It doesn’t fail every day. It fails on the day your business cares the most.

So what do we do instead?

We stop trying to make the whole world transactional.

We split the problem into:

- local atomic state change

- reliable intent publication

- durable workflow progression

- safe retries everywhere

That’s outbox + saga thinking.

The core decomposition: State, intent, and side effects

A useful mental model is to separate three things:

1) State

What your database stores.

This is where you can be atomic.

2) Intent

What you want to happen next.

This must be durable, even if the system crashes immediately after writing it.

3) Side effects

Things outside your DB:

- charging cards

- sending emails

- calling external APIs

- publishing messages

These must be retryable and idempotent.

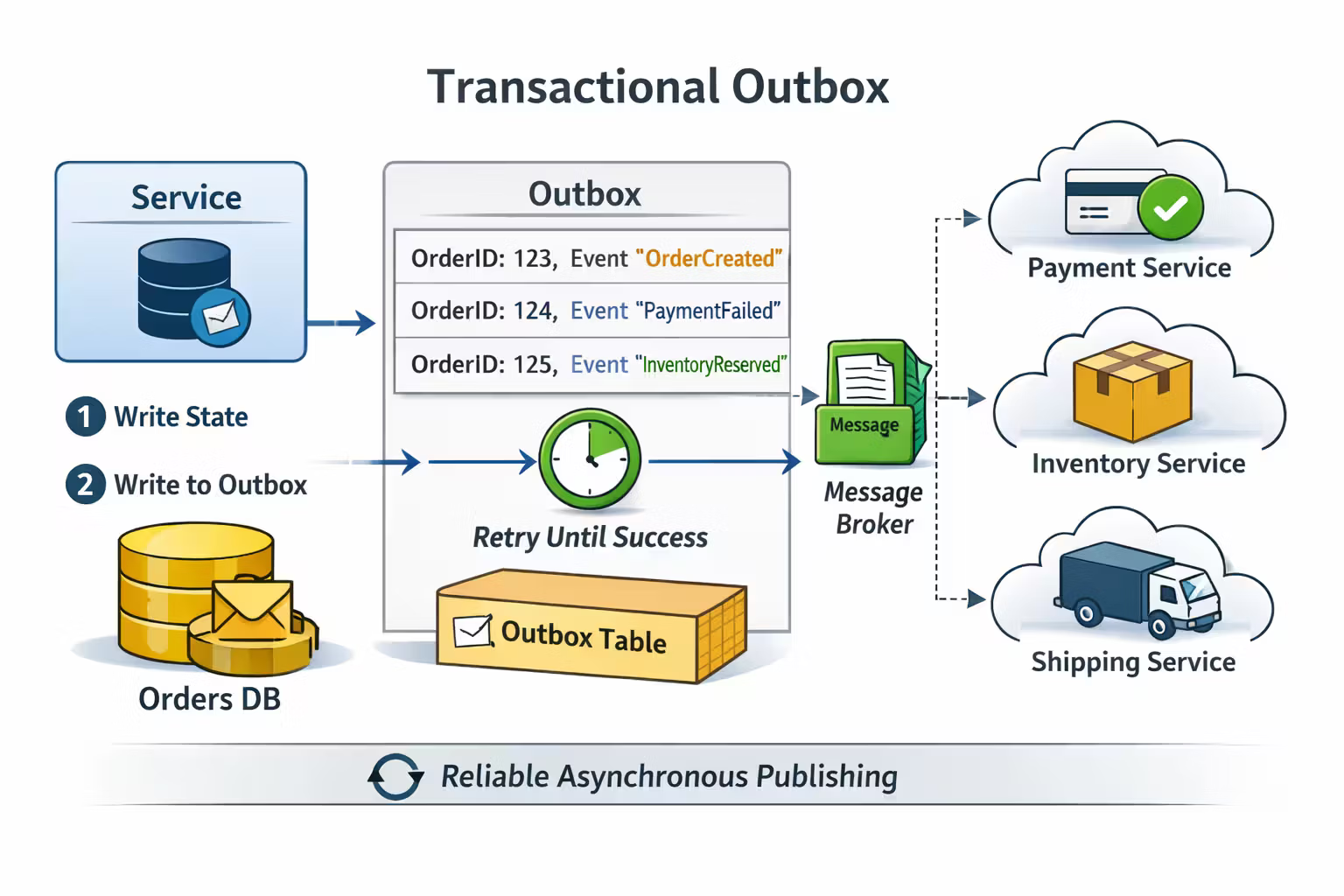

Pattern 1: The Transactional Outbox (make “DB write + publish” reliable)

The outbox pattern is simple:

- In the same DB transaction where you update state, you also write an outbox row describing the event/command to publish.

- A separate dispatcher reads the outbox table and publishes messages (to a queue, topic, webhook, etc.).

- Publication is retried until successful.

- Consumers process at-least-once — meaning duplicates are normal, and your handlers must be safe.

Why it works

Because your atomic unit becomes:

“State update and durable intent recording happen together.”

If the service crashes after the transaction commits, the outbox record still exists.

No ghost events. No lost events.

Where teams mess it up

Publishing to a queue inside the DB transaction seems reasonable until the queue call succeeds and the DB commit fails (or times out).

Now you published an event for state that never committed.

That’s how you get ghost jobs and phantom emails.

Most messaging systems are at-least-once in real operation.

Exactly-once is a special kind of expensive, fragile promise.

Design for duplicates:

- add idempotency keys

- use unique constraints

- store processed message IDs (inbox)

Outbox needs lifecycle management:

- retention window

- archiving

- deletion only after confirmed publish

- metrics on backlog size and publish latency

Pattern 2: Sagas (make long workflows correct under failure)

An outbox reliably publishes intent.

But many business flows are multi-step and multi-owner:

- create order

- authorize payment

- reserve inventory

- schedule shipping

- notify customer

You need a durable way to progress through steps and handle failure.

That’s a saga.

A saga is a workflow with:

- steps

- state

- timeouts

- retries

- compensation (if you need to undo)

There are two main styles:

Orchestration

A coordinator service owns the state machine and tells participants what to do next.

Choreography

Services react to events and emit events. The “flow” emerges from subscriptions.

Which one should you choose?

My rule of thumb:

- Choreography for simple, mostly-linear flows with low stakes.

- Orchestration for anything with:

- money

- customer-facing guarantees

- multi-step timeouts

- complex branching

- operational need for “where is this stuck?”

Until the flow changes. Then you discover you built a distributed state machine with no single place to debug it.

“Eventually correct” is not “eventually consistent”

Teams often treat these as synonyms.

They’re not.

Eventual consistency (the weak promise)

“Things will probably converge later.”

Eventually correct (the strong promise)

“Under retries and failures, the system converges to a correct business outcome, and we can prove it.”

That proof comes from engineering discipline:

- idempotency

- deterministic state machines

- explicit timeouts

- compensations when needed

- observability of stuck flows

A concrete example: Order → Payment → Inventory → Shipping

Let’s design a flow with realistic failure behavior.

The invariant

Charge at most once.

(Everything else we can repair.)

The architecture decision

- Orders DB is the authoritative writer for order state.

- Payment service owns payment state (and idempotency).

- Inventory service owns stock reservations.

- Shipping service is eventually consistent.

The flow (orchestrated saga)

- Order service creates

Order(PENDING_PAYMENT)and writes an outbox messageAuthorizePayment(orderId, amount, idempotencyKey). - Payment service processes the command:

- uses the idempotency key to ensure at-most-once charge

- emits

PaymentAuthorizedorPaymentFailed

- Orchestrator transitions order:

- on authorized → request inventory reservation

- on failed → mark order

FAILED_PAYMENT

- Inventory responds:

- on reserved → request shipping

- on failed → trigger compensation (refund/cancel auth) if needed

- Shipping schedules and emits

ShipmentScheduled - Order becomes

COMPLETED

The key is not the happy path.

It’s how every step behaves under retries, duplicates, and timeouts.

The non-negotiables of distributed correctness

You can copy patterns forever and still ship brittle systems if you miss the fundamentals.

Here are the four constraints I treat as mandatory.

Idempotency everywhere

Every handler must be safe to run twice. Duplicates are normal.

Durable state machines

Workflow state must survive crashes. If the process dies, the truth must remain.

Explicit timeouts

If you don’t define time, the network defines it for you (and you won’t like the result).

Poison pill containment

Failures that can’t be auto-retried must go somewhere (DLQ / dead-letter table) with visibility.

Implementation blueprint: Outbox + Dispatcher + Consumers

This isn’t a framework.

It’s a set of boring, repeatable mechanics.

Define a stable message envelope

Include:

- message ID

- event type / command type

- aggregate ID (e.g., orderId)

- idempotency key

- createdAt

- payload

Write state + outbox in one DB transaction

If the transaction commits, you are guaranteed the intent exists.

Build a small dispatcher

The dispatcher:

- polls or streams new outbox rows

- publishes to your broker (or HTTP endpoint)

- marks rows as published (or stores publish attempts)

- uses backoff + jitter on failure

- emits metrics (lag, backlog, failures)

Make consumers idempotent

Use one of:

- unique constraint on

(idempotency_key)in your write model - inbox table of processed message IDs

- upsert semantics / compare-and-swap updates

Add a dead-letter path

If a message fails N times:

- move it to DLQ

- alert

- provide a safe replay mechanism

at-least-once delivery + idempotent handlers + dead-lettering = sanity.

Choosing your consistency boundaries

The best architectural move is often not “saga everything.”

It’s choosing boundaries intentionally:

- Single-writer aggregates for strong invariants

- Async projections for read models

- Event-driven integration for loose coupling

- Manual repair paths for rare edge cases (yes, really)

Here’s the decision heuristic I use:

Pick a single system of record for the invariant.

Everything else can become:

- a projection

- an async downstream update

- a reconciled view

Users tolerate eventual updates if the product is honest:

- show “processing…”

- provide status visibility

- don’t promise immediate finality when you don’t have it

Not everything needs real-time coupling.

For rare inconsistencies:

- detect with periodic reconciliation

- repair with compensations or operator tooling

- learn from incident patterns

The architect’s checklist

If you’re reviewing a “distributed data” design, ask these questions:

- What are the explicit invariants?

- Who is the single writer for each invariant?

- Where are idempotency keys generated and enforced?

- What’s the delivery semantics (at-most-once, at-least-once)?

- Where is workflow state stored durably?

- How do timeouts work at every boundary?

- How do we observe backlog, retries, and stuck workflows?

- Where do poison messages go?

- How do we replay safely?

- What’s the reconciliation story?

If the design can’t answer those, it’s not an architecture yet.

It’s hope.

Resources

Transactional Outbox (pattern)

A practical approach to “DB write + publish” without ghost events or lost messages.

FAQ

Outbox solves one specific problem: reliable publication of intent.

Sagas solve a different problem: durable progression of multi-step workflows.

If your flow is one-and-done, outbox + idempotent consumers might be enough.

If your flow has multiple steps, branching, or compensations, you want saga thinking.

No.

Eventual consistency is a tradeoff.

It’s acceptable where:

- the invariant is not critical

- user experience can tolerate delay

- you can reconcile/repair when reality diverges

For money, security, and irreversible actions, design stronger invariants.

Start with:

- a modular monolith (single DB transaction for invariants)

- outbox for integration events

- idempotency keys for external calls

- a small dispatcher

- explicit DLQ handling

You can evolve into deeper workflows as the system earns it.

What’s Next

This month was about making state changes safe across boundaries.

Next month is about making APIs safe across time.

Because even if your data is eventually correct…

your clients will still break if your contracts aren’t.

API Evolution at Scale: Compatibility, Contracts, and Consumer-Driven Testing

APIs don’t fail because they’re slow — they fail because they change. This month is about designing contracts you can evolve, enforcing compatibility automatically, and scaling teams without “everyone upgrade on Tuesday.”

Security for Builders: Threat Modeling and Secure-by-Default Systems

Security isn’t a checklist you add at the end — it’s a set of architectural constraints. This month is about threat modeling that fits real teams, and defaults that prevent whole classes of incidents.