Why NLP Was Hard: RNN Pain, Vanishing Gradients, and the Limits of “Memory”

Before transformers, language models tried to compress entire histories into a single hidden state. This post explains why that was brittle: depth-in-time, vanishing/exploding gradients, and the engineering limits of “memory” — and why attention was inevitable.

Axel Domingues

January was the “architect’s reset”:

LLMs are not deterministic functions.

They’re probabilistic components — and reliability has to be designed.

But if you want good instincts for modern LLM behavior, you need one piece of history:

Why language modeling was hard before transformers.

Not in a “fun trivia” way — in a failure-modes way.

Because a lot of what still goes wrong in LLM products (context loss, hallucination under missing evidence, sensitivity to phrasing) makes more sense when you understand what earlier NLP systems were fighting.

This month is the prequel:

- what RNNs promised (“learn memory!”)

- what they actually delivered (“mostly short-term”)

- and why attention was an engineering inevitability, not a math flex.

The core problem

NLP needed long-range dependencies. RNNs tried to carry them through a single hidden state.

The core failure

Unrolling makes RNNs deep in time → vanishing/exploding gradients → brittle training.

The deeper limitation

“Memory” is a bottleneck: compressing a long history into one vector loses information and induces interference.

The setup for March

Attention breaks the bottleneck: direct access to past tokens + parallelism + better gradient paths.

The pre-transformer dream: “just model sequences”

Language is a sequence problem:

- meaning depends on earlier words

- syntax creates long-distance constraints

- ambiguity resolves with context

- and the useful signal is often not local

So when RNNs became practical, the pitch was incredibly appealing:

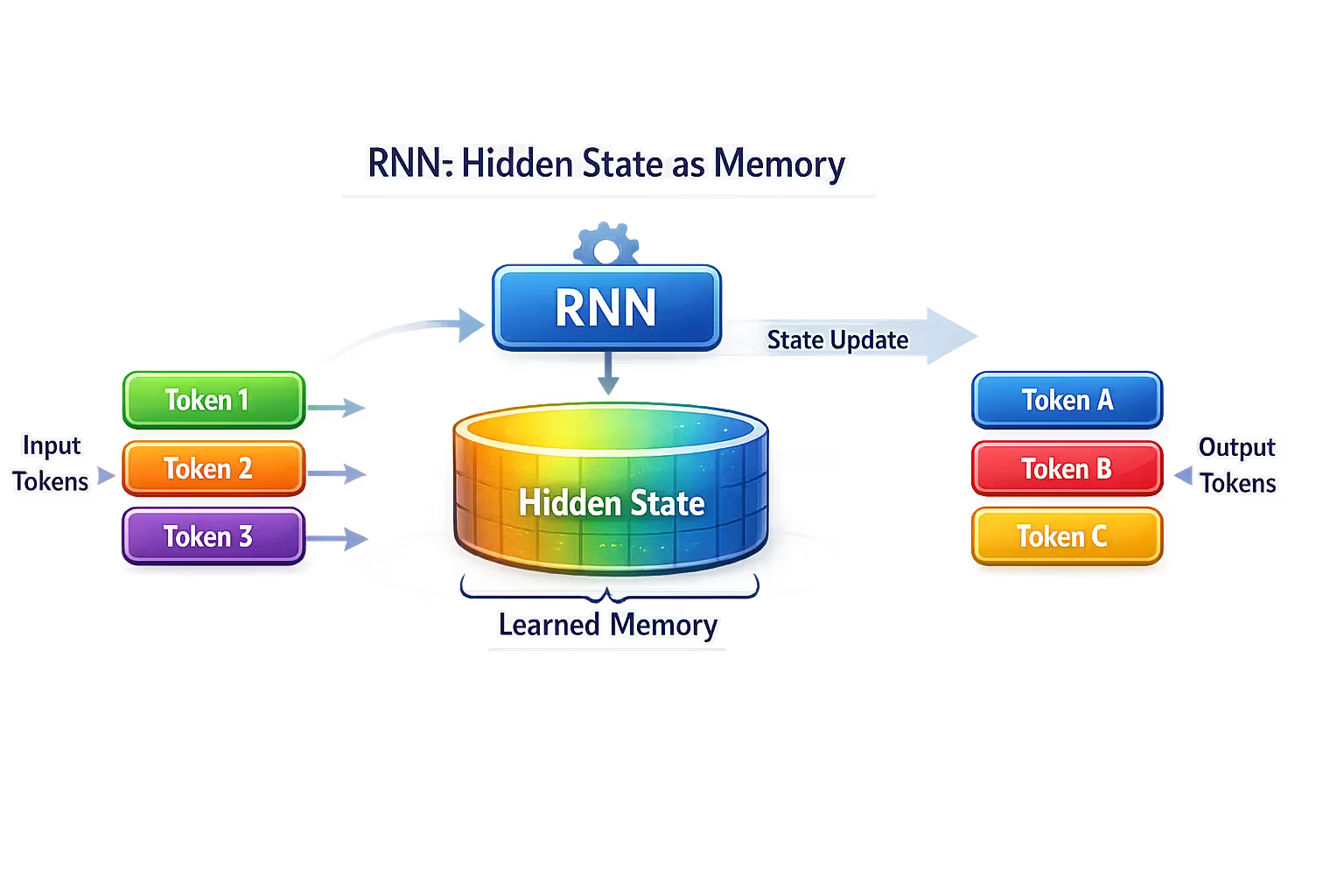

Feed tokens one by one, keep a hidden state, and learn “memory.”

That framing is not wrong.

But the engineering reality was:

- the hidden state becomes a compression bottleneck

- training becomes a fight with gradients

- and scaling hits a sequential computation wall

To understand why, we need the two ideas that shaped everything:

- Depth in time

- The memory bottleneck

Mini-glossary: the only terms we need

- Token: a discrete unit the model consumes/produces (word, subword, character).

- Hidden state: the running vector summary an RNN carries forward through time.

- Unrolling: rewriting the recurrence as a long computation graph with repeated steps.

- Depth in time: unrolling for T steps behaves like a T-layer deep network (shared weights).

- Long-range dependency: when correct prediction depends on information many steps back.

- Interference: new information overwrites or distorts older information in a fixed-size state.

- Bottleneck: a narrow representation that must carry too much information.

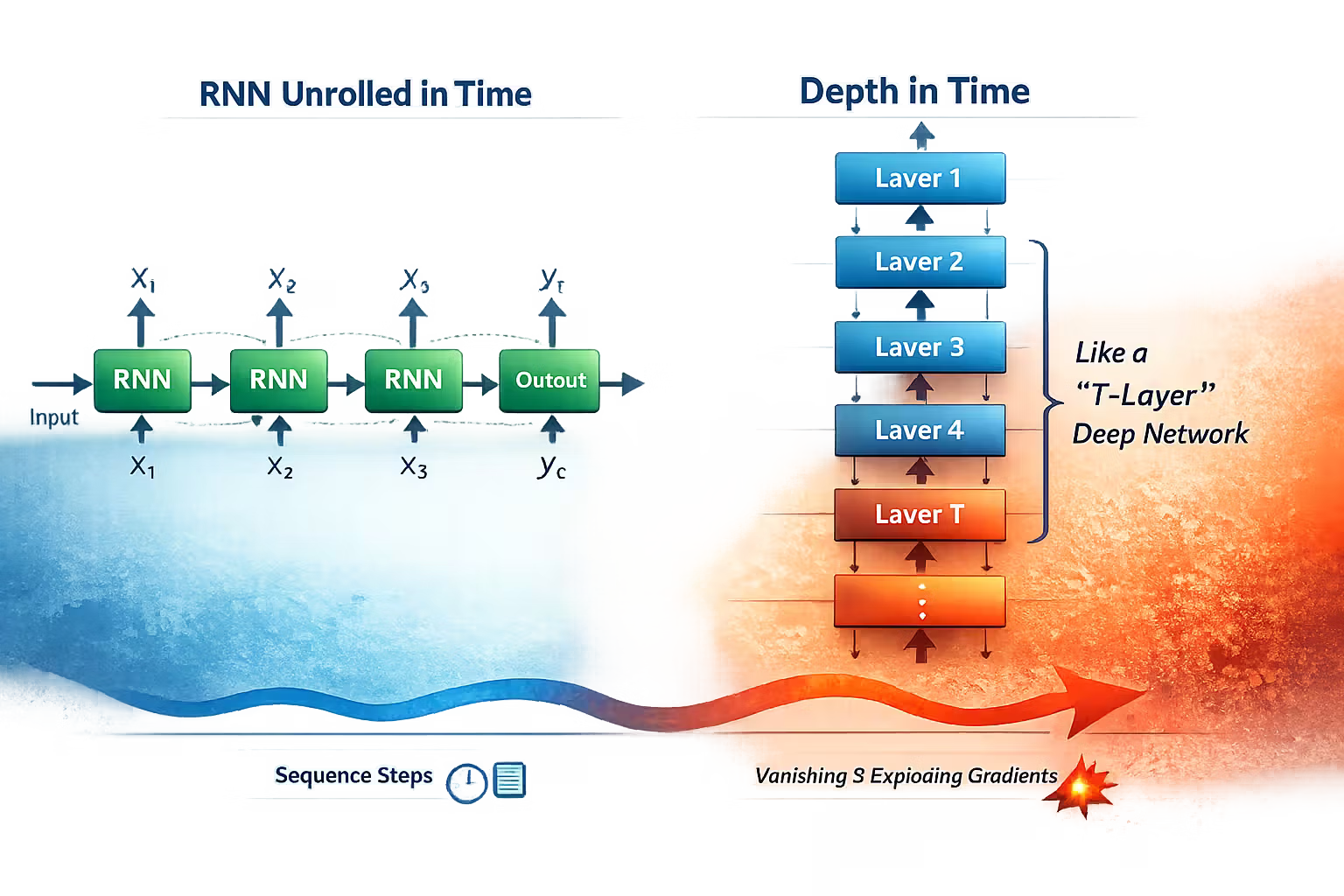

1) Depth in time: why RNNs reintroduced vanishing gradients

Here’s the subtle trap:

An RNN can be “one layer”… but when you unroll it for 200 steps, it behaves like a 200-layer deep computation graph.

Same weights, repeated many times.

And the backprop story is brutal:

- gradients must travel backward through the entire unrolled chain

- small multiplicative effects compound

- so gradients either shrink to nothing or blow up

That’s the familiar deep learning lesson — just relocated into time.

Depth in time is still depth.

What this looked like in practice

The failure patterns were so consistent they became muscle memory:

Learns short-term only

Local patterns improve, but long-range dependencies never get reliably better.

Sudden instability

Training looks fine… then spikes, diverges, or produces NaNs.

Hyperparameter cliff edges

Tiny changes in LR, init, or sequence length produce totally different outcomes.

“Seems to work” but is brittle

One run looks good; the next seed collapses. Results don’t survive repetition.

If this sounds like reinforcement learning instability… that’s not a coincidence.

It’s the same underlying theme:

learning signal is fragile when it has to pass through long chains.

2) The “memory” bottleneck: one vector can’t be your whole history

Even if you solved gradients perfectly, RNNs still have a structural limit:

They compress the entire past into a single fixed-size hidden state.

That’s a bottleneck.

It forces a constant tradeoff:

- keep old information

- incorporate new information

- but you only have so many dimensions to do both

So the model tends to learn a recency bias:

- keep what helps next-token prediction now

- let distant info fade, unless it’s extremely frequent and useful

Not because they are stupid — because they are forced to compress.

The two memory failure modes

As the sequence progresses, new content overwrites older content in the hidden state.

The model can’t keep “everything,” so it learns what to forget.

That often means it forgets what humans consider “important,” because the objective is next-token likelihood.

Even if a piece of information is still “in” the hidden state, it can be encoded in a tangled way.

The model might not be able to access it cleanly when needed, because retrieval becomes a learned decoding problem, not an explicit read.

This matters for product intuition:

Many modern “LLM weirdness” behaviors are still about what context is accessible versus merely “present somewhere in the prompt.”

We’ll come back to that.

What LSTMs fixed (and what they didn’t)

LSTMs were an engineering response to the exact pain above:

- gates regulate what to write, keep, and forget

- the memory cell creates a more stable pathway for gradient flow

- training becomes less catastrophic

They made sequence learning practical.

But they didn’t remove the core constraints:

- still sequential (you can’t parallelize time steps well)

- still bottlenecked (memory is fixed-size)

- still hard for very long dependencies

That approach hits a ceiling.

Why NLP was hard in production, not just in papers

This is the part that matters for senior engineers:

RNN-based NLP systems weren’t just “less accurate.” They were operationally fragile.

Latency and throughput: the sequential wall

RNN inference is fundamentally sequential:

- step t depends on step t-1

- so you can’t process the whole sequence in parallel

That means:

- lower throughput for long sequences

- higher tail latency under load

- harder batching

- more expensive serving for the same product experience

If you’ve ever tried to scale a system that can’t parallelize its hottest loop, you know how that ends: you buy hardware and still lose on p99.

Evaluation: the long-dependency lie

Many datasets reward local heuristics. So models can “look good” while failing the real problem:

- coreference (“it”, “they”, “that”)

- long-distance agreement

- late disambiguation

- multi-sentence reasoning

This is the same theme as 2019–2020 trading work:

If your evaluation distribution is biased toward easy shortcuts, you won’t notice brittleness until production.

The architect’s translation: RNN limitations map to LLM failure modes

You might be thinking:

“Cool history lesson. But we use transformers now.”

Yes — but the software lesson persists:

- models behave according to what context is usable

- and they fail when forced to guess

So here’s the translation table I keep in my head when designing LLM features:

| Old problem (RNN era) | Modern manifestation (LLM products) | What you do about it |

|---|---|---|

| Memory bottleneck | Context window limits, recency effects | Retrieval + context budgeting + summarization discipline |

| Weak long-range credit | Model ignores earlier constraints | Strong system prompts + structure + tool constraints + verification |

| Training instability | Unstable behavior across versions | Evals + canary rollouts + regression suites |

| “Looks good on dataset” | “Worked in a demo” but fails live | Realistic eval sets + adversarial prompts + telemetry |

| Sequential cost wall | Token cost + latency budgets | Streaming, caching, smaller models, routing policies |

You don’t ship “model intelligence.” You ship a behavior under constraints.

Practical: how to debug “memory failure” in an LLM feature

Even though we’re not building RNNs anymore, the debug mindset is identical.

When your LLM “forgets” something, don’t argue with it.

Instrument the system.

Inspect the assembled context

- What did we actually send?

- Did we truncate earlier content?

- Did retrieval return the relevant facts?

- Did we include conflicting sources?

Check instruction hierarchy

- System message vs developer message vs user content

- Did user content contain injection-like directives?

- Did we place constraints early and clearly?

Reduce degrees of freedom

- Force a structured format

- Require citations to provided sources

- Disallow unsupported claims (“If not in sources, say you don’t know”)

Add a minimal eval case

Take the failing conversation and turn it into:

- a repeatable prompt

- with a stable context snapshot

- and a pass/fail expectation

Decide the fallback behavior

If the model can’t answer reliably:

- ask a clarifying question

- route to search/retrieval

- or escalate to human review

That last bullet is the key architectural move:

abstention is a feature.

The real “NLP was hard” takeaway

RNNs failed in ways that made engineers cynical:

- “It works until it doesn’t.”

- “It’s sensitive to everything.”

- “It forgets the one thing you care about.”

- “Scaling it is expensive.”

Transformers didn’t succeed because someone invented a prettier equation.

They succeeded because they attacked the two structural walls:

- bottlenecked memory

- sequential computation

And the tool they used was conceptually simple:

Let the model look back directly.

That’s attention.

Which is why March is inevitable.

FAQ

Because they made sequence learning concrete.

They gave us a workable mental model for:

- recurrence

- unrolling

- depth in time

- and why gradients fail across long chains

That intuition is still valuable when reasoning about modern LLM behavior (especially context and failure modes).

They made long-term dependencies more learnable and training more stable.

But they didn’t remove:

- the fixed-size memory bottleneck

- or the sequential compute wall

So they improved the ceiling, but they didn’t remove the ceiling.

That “the model saw the input” is not the same as “the model can reliably use the input.”

Architecturally, this forces:

- context budgeting

- grounding and retrieval

- structured outputs

- verification

- and abstention UX when you care about correctness.

What’s Next

Now we’ve earned the intuition:

- sequences create depth in time

- gradients don’t like long chains

- “memory” as a single vector is a bottleneck

- and operationally, sequential models hit latency/cost walls

Next month we look at the breakthrough that changed everything:

Transformers: Attention as an Engineering Breakthrough (Not a Math Flex)

Because attention isn’t just a trick.

It’s a new system contract for memory, scale, and reliability.

Transformers: Attention as an Engineering Breakthrough (Not a Math Flex)

RNNs made sequence learning feel like fighting gradients. Transformers made it feel like building systems: parallelism, short gradient paths, and a memory mechanism you can scale. This post explains attention as an engineering unlock—and what it implies for real software.

Software in the Age of Probabilistic Components

LLMs aren’t “features” — they’re probabilistic runtime dependencies. This post gives the mental model, contracts, failure modes, and ship-ready checklists for building real products on top of them.