Transformers: Attention as an Engineering Breakthrough (Not a Math Flex)

RNNs made sequence learning feel like fighting gradients. Transformers made it feel like building systems: parallelism, short gradient paths, and a memory mechanism you can scale. This post explains attention as an engineering unlock—and what it implies for real software.

Axel Domingues

February was the “why NLP was hard” month.

RNNs could represent sequence behavior… but training them was a constant negotiation with physics:

- long chains

- fragile gradients

- sequential compute

- and the feeling that “memory” was a promise you couldn’t reliably cash

March is where that story flips.

Transformers didn’t win because of a clever equation.

They won because they turned sequence modeling into something hardware can chew and optimizers can survive.

The breakthrough is attention — not as “math,” but as a new kind of system component:

A learnable, content-addressable routing layer that can connect any token to any other token in one step.

That one-step connectivity changes everything:

- gradient flow

- parallelism

- capacity scaling

- and eventually… product reliability (because you can train bigger, better models predictably)

The goal this month

Build a mental model of transformers that helps you ship LLM features without mysticism.

The engineering unlock

Transformers replace sequential “memory updates” with parallel attention + short paths.

The real payoff

Trainability + throughput → scale → capability. “Better models” is an operational outcome.

The production lens

Attention implies a new cost model: tokens, context windows, KV caches, latency, and failure modes.

Mini-glossary (as used in this post)

- Token: a chunk of text the model processes (not always a word).

- Embedding: the vector representation of a token (the model’s internal “meaning space”).

- Attention: a learned mechanism that decides which other tokens matter for the current token.

- Self-attention: attention where queries/keys/values all come from the same sequence.

- Causal (masked) attention: token t can’t look at tokens after t (used for generation).

- Encoder/decoder: classic transformer split (translation-style). LLMs are typically decoder-only.

- Residual path: a skip connection that keeps optimization sane (also: a stability feature).

- KV cache: cached attention keys/values from previous tokens to speed up generation.

The transformer elevator pitch (without the math)

Here’s the simplest operational definition I’ve found useful:

A transformer layer is “compute features locally” (MLP) + “route information globally” (attention), repeated many times, with stability scaffolding (residuals + normalization).

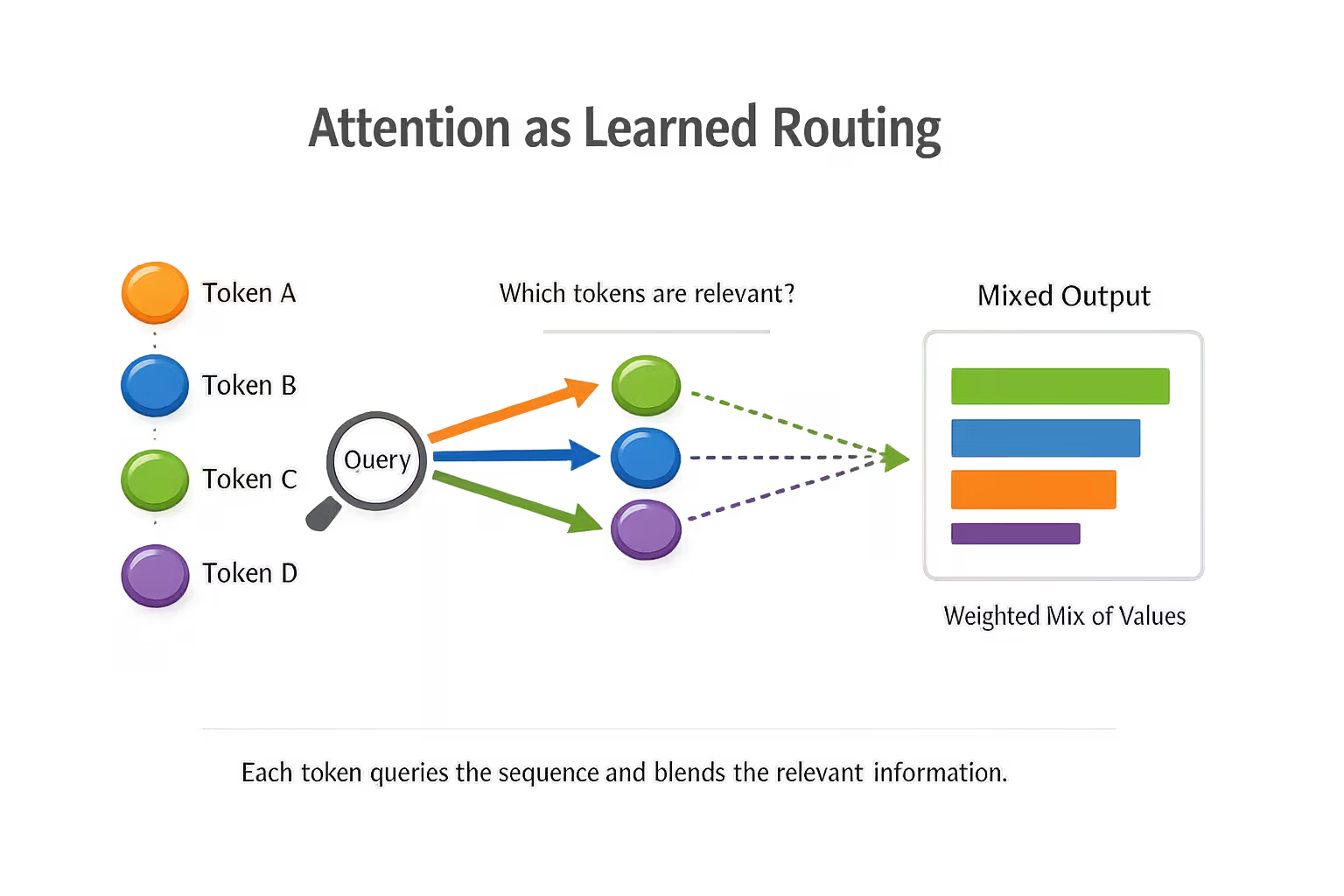

The attention part is the star:

- each token produces a query

- every token produces a key and value

- the query “asks” which keys are relevant

- the output is a weighted mix of values

That’s it.

It’s not a memory cell. It’s not a loop.

It’s a routing decision that happens in parallel.

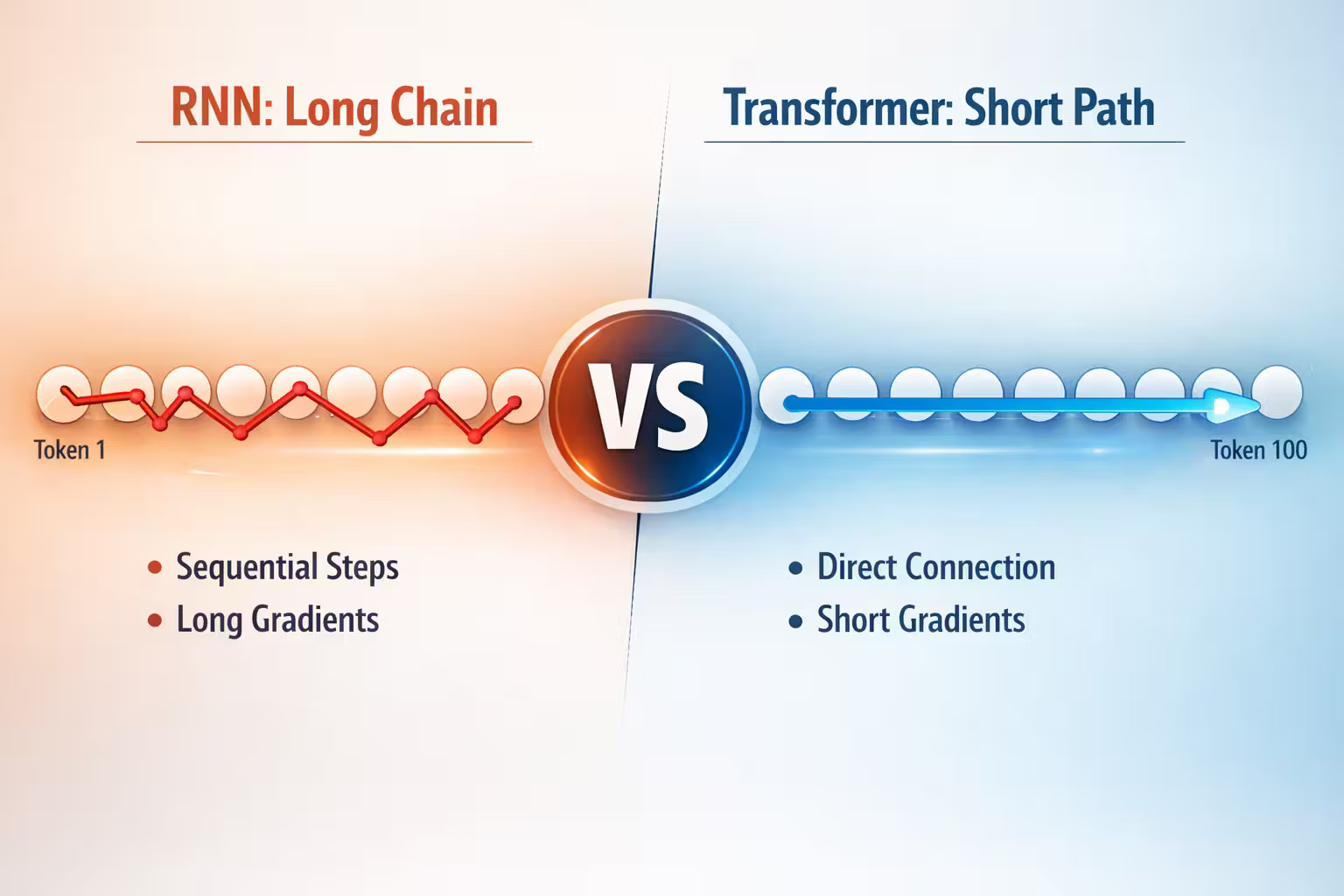

Why RNNs struggled (the constraint that mattered)

RNNs have two brutal constraints that show up as engineering pain:

1) Sequential compute

You can’t compute step t+1 until step t is done.

That kills throughput and makes scaling expensive.

2) Long gradient paths

Even if you “unroll” for training, the learning signal has to travel through a long chain.

In practice that means:

- vanishing gradients (nothing learns far back)

- exploding gradients (everything breaks)

- fragile hyperparameters

- and a constant battle for stability

I wrote about that pain explicitly in 2017 (The Pain of Training RNNs).

The transformer’s real innovation is that it makes those constraints optional.

Attention is a shortcut through time

The transformer changes the connectivity of the computation graph.

With an RNN:

- the only path from token 1 to token 100 is the chain of hidden states

With attention:

- token 100 can directly “look at” token 1 in a single step

That means:

- shorter gradient paths

- faster credit assignment

- and less “memory degradation” through repeated transforms

They’re better because they create shorter paths for information and learning signals.Transformers aren’t “better at memory” because they store more.

The parallelism story (why this was an engineering breakthrough)

RNNs force a time loop.

Transformers let you compute token representations in parallel (during training):

- all tokens → embeddings

- attention/MLP layers operate on the whole sequence as a matrix

- GPUs/TPUs do what they’re built for: big dense operations

That parallelism is not a convenience.

It is what made “scale” economically viable.

And scale is what turns a model from:

- “cute demo” to

- “general tool you can productize”

It turned sequence learning into batchable compute.

The transformer block (what’s inside, conceptually)

A production mental model that holds up:

- Self-attention (global routing)

- MLP / feed-forward (local feature compute)

- Residual connections + normalization (stability scaffolding)

Repeat that N times.

Most LLMs today are “decoder-only transformers,” meaning:

- they use causal attention

- they predict the next token

- and generation is “keep predicting the next token”

Attention

“Which previous tokens matter right now?” (routing)

MLP

“Given that info, compute a better representation.” (feature transformation)

Residual + norm

“Don’t let depth destroy trainability.” (stability)

Stack depth

“Repeat until the model can express complex behaviors.” (capacity)

Transformers don’t store memory.No “explicit memory cell.”

They reconstruct what they need by routing across the context.

The two transformer modes that matter for engineers

When you build on transformers, two modes matter more than the paper diagrams.

Training mode: parallel, expensive, stable-ish

- you process sequences in batches

- you compute attention across the sequence

- you update weights

This is where transformers win versus RNNs: parallelism + stable optimization at depth.

Inference mode: sequential generation, optimized by caching

At inference, you generate one token at a time.

So you might ask:

“If generation is sequential anyway, why is the transformer an improvement?”

Because:

- the model is already trained (thanks to parallelism)

- and inference is accelerated by KV caching

KV cache (why it exists)

When generating token t, attention needs keys/values from tokens 1..t-1.

Naively, you’d recompute everything each step.

Instead, you cache keys/values per layer for previous tokens.

So each new token mostly computes:

- the new token’s query/key/value

- attention against cached keys/values

- the MLP stack

This is why LLM inference has a distinct cost profile:

- prefill (processing the prompt / context) vs

- decode (token-by-token generation)

- prefill cost scales with context length

- decode cost scales with output length

Attention’s cost model (the part product teams learn late)

Attention is powerful, but not free.

The naive cost grows quickly with context length because every token can attend to many others.

What that means operationally:

- longer prompts increase latency and cost

- longer contexts amplify the chance of “prompt collisions” (irrelevant details stealing attention)

- retrieval strategies matter (we’ll get to RAG later this year)

- your product’s reliability will depend on context assembly discipline

If you stuff the context with noise, the model will confidently route to noise.

“Attention is all you need” as a systems statement

The famous title is easy to misread.

It doesn’t mean:

- attention replaces the rest of deep learning

- or that the math is the point

It means something more practical:

If you can route information flexibly with short paths, the rest of the network can be boring and scalable.

Which is a very 2020s engineering story:

- make the core primitive strong

- then scale it with infrastructure

This is also why the “transformer era” became a platform era:

- better accelerators

- better kernels

- better distributed training

- better data pipelines

- better inference serving

The architecture and the infrastructure co-evolved.

What this changes for software architects

If you build with transformers, you’re building with a new kind of component:

- it is probabilistic

- it is context-sensitive

- it is expensive per token

- it produces outputs that sound authoritative even when wrong

- it can be steered—but not controlled like deterministic code

So the “transformer understanding” that matters is not academic.

It’s architectural.

Here are the real design consequences that start now:

Context is an input surface

Your system must assemble context intentionally (not “just dump everything”).

Cost is a product constraint

Tokens are your new currency: budget, cache, and throttle like an adult.

Reliability needs boundaries

Decide what must never be wrong, and keep that in deterministic code paths.

Evaluation becomes a discipline

You can’t reason about correctness without a harness (goldens, regressions, telemetry).

A practical checklist: “Do I actually understand transformers enough to ship?”

This is my “architect’s minimum bar.”

Know the two-phase inference cost model

Can you explain prefill vs decode and why long prompts are expensive?

Know what KV cache is and why it matters

Can you explain why multi-turn chat can be fast or slow depending on caching and prompt growth?

Know what causal attention implies

Can you explain why decoder-only models generate left-to-right and why that affects controllability?

Know why scale matters (and why it’s not “just bigger”)

Can you explain why a modest architecture improvement can unlock large capability jumps when combined with data + compute?

Know where transformers fail as system components

Can you articulate hallucinations as “token-likelihood optimization,” not “the model lying”?

If you can’t answer those, you’ll still ship something… but you’ll be debugging with superstition.

Resources

FAQ

They’re not “better memory” in the sense of a stronger memory cell.

They’re better at using context because attention gives short paths:

- information can connect directly across the sequence

- gradients can assign credit without crossing a long chain

That makes long-range dependencies learnable at scale.

Parallelism matters primarily for training (where most compute happens).

At inference, you still generate token-by-token, but:

- KV caching avoids recomputing past tokens

- the model you’re serving exists because training was parallelizable and scalable

No.

Attention is a routing mechanism, not a truth mechanism.

If your context is noisy or adversarial, the model can route confidently to the wrong signals. That’s why context assembly and evaluation become product disciplines.

Encoder-decoder models are great for “transform input → output” tasks (translation-style).

Decoder-only models are trained to predict the next token and are the backbone of most LLM chat systems. They’re simpler to scale and align well with “generate text” as a universal interface.

What’s Next

Now we have the architecture primitive.

Next month is the other half of the story:

Pretraining Is Compression: Tokens, Datasets, and Emergent Skill

Because transformers didn’t become powerful just because of attention.

They became powerful because pretraining turned the internet into:

- a compression problem

- a representation learning machine

- and eventually… a general-purpose interface for software.

Pretraining Is Compression: Tokens, Datasets, and Emergent Skill

Pretraining isn’t “learning facts.” It’s learning to compress a giant slice of the internet into a predictive machine. This post gives senior engineers the mental model: tokens, data mixtures, scaling, and why capabilities seem to ‘emerge’—plus the practical implications for cost, reliability, and product design.

Why NLP Was Hard: RNN Pain, Vanishing Gradients, and the Limits of “Memory”

Before transformers, language models tried to compress entire histories into a single hidden state. This post explains why that was brittle: depth-in-time, vanishing/exploding gradients, and the engineering limits of “memory” — and why attention was inevitable.