Why Deeper Networks Are Harder to Train Than I Expected

I assumed “more layers” would just mean “more power.” Instead I discovered that depth introduces a new failure mode - gradients can disappear (or explode) long before the model learns anything useful.

Axel Domingues

January taught me that neurons are familiar. February taught me that backprop is the chain rule, implemented like engineering.

So in March I expected things to scale smoothly:

If a small network can learn, a bigger network should learn even better… right?

That assumption lasted about five minutes.

Because the first practical lesson of deep learning is not about accuracy.

It’s about trainability.

And deeper networks are harder to train in a way that my 2016 machine learning intuition didn’t fully prepare me for.

What this post explains

Why “more layers” introduces a new failure mode: the learning signal can vanish or explode before it reaches early layers.

What to watch while training

Not just loss/accuracy. Also: gradient size per layer and signs of saturation.

The big mental shift

Deep learning is often about keeping training dynamics healthy, not just “adding capacity.”

The Mistake I Carried From Classical ML

In 2016, most of my models were shallow:

- linear regression

- logistic regression

- “single hidden layer” neural nets

- SVMs (which are powerful but don’t go deep)

- even PCA and clustering are “one-step” algorithms conceptually

In that world, if a model wasn’t performing well, the usual suspects were:

- high bias → model too simple

- high variance → model too flexible

- bad features → improve representation

- bad lambda → tune regularization

And most importantly:

If I make the model more expressive, it should be able to fit better.

With deep networks, I learned a painful truth:

A deep model can contain the right solution and still fail to learn it because the learning signal never reaches the early layers.

- Gradient (learning signal): the “how to change” message backprop sends from the loss to earlier layers.

- Vanishing gradients: the signal becomes so small early layers barely update.

- Exploding gradients: the signal becomes so large training becomes unstable.

- Saturation: an activation “flattens out,” reducing useful learning signal.

- Trainability: whether optimization can actually reach the solution the model could represent.

The Learning Signal Has to Travel

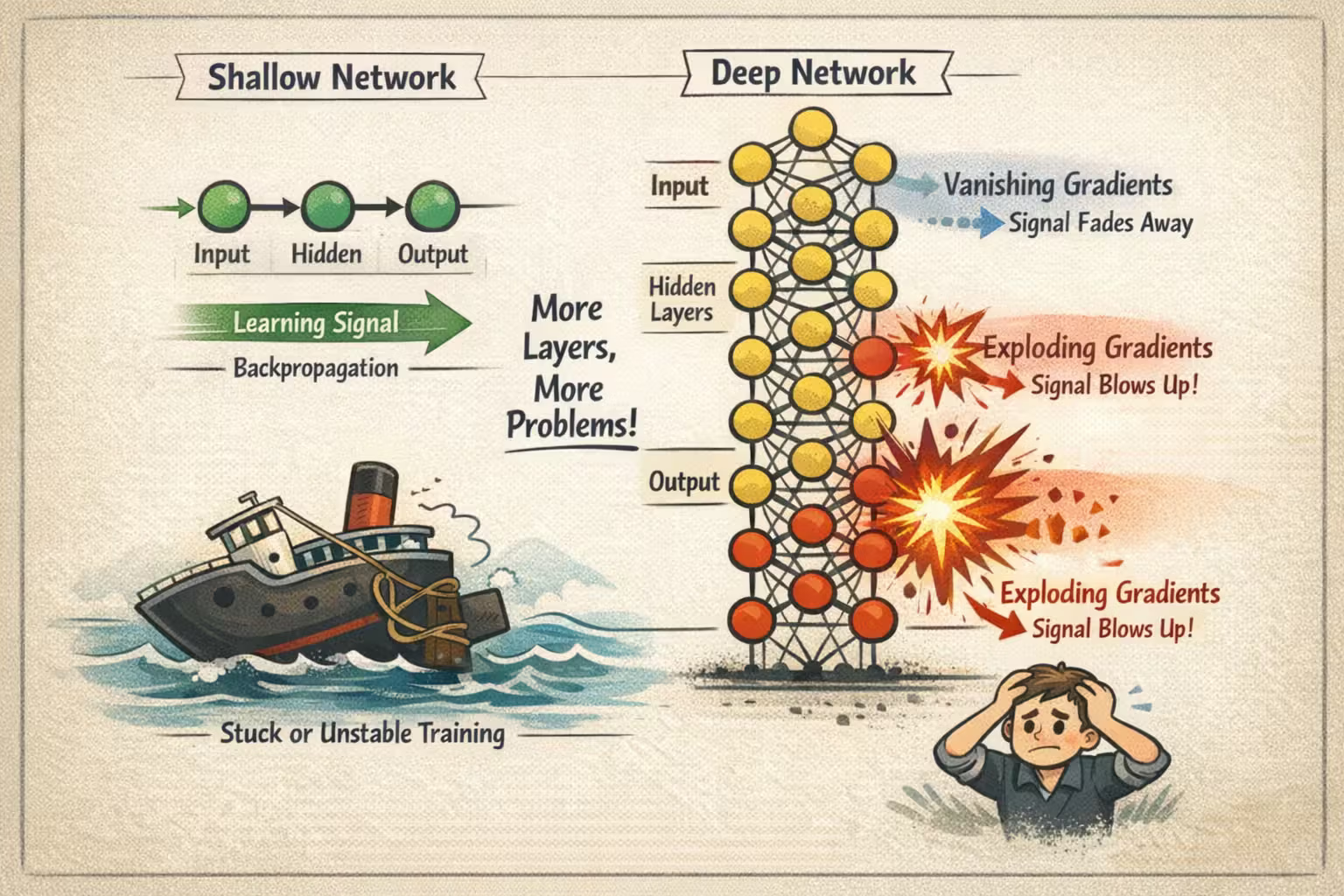

Backpropagation sends gradients from the output layer back toward the input.

In a shallow model, that path is short.

In a deep model, the gradient has to pass through many layers, and each layer transforms it.

That’s where everything goes wrong.

I kept imagining it like a pipeline:

- the loss produces a gradient “signal”

- that signal travels backward

- each layer either preserves it, shrinks it, or amplifies it

By the time it reaches the early layers, it might be:

- so tiny it’s effectively zero (vanishing gradients)

- or so large it blows up (exploding gradients)

Either way, the model doesn’t learn correctly.

Vanishing Gradients (What It Felt Like)

The frustrating part is how “normal” vanishing gradients look.

Nothing crashes. Loss might decrease slightly. The model might appear to be training.

But the early layers barely change.

The network acts like it’s stuck.

It’s like trying to steer a ship where the wheel is connected to the rudder with a rubber band.

You turn. You wait. Nothing happens.

This was the first month where I realized: deep learning is not just about having a model — it’s about keeping gradients alive.

Why This Happens (Without Turning It Into Math)

Here’s the intuition I wrote down for myself:

Backprop is multiplication. Not in the “matrix multiply everything” sense, but in the “each layer scales the gradient” sense.

Each layer contributes a factor to the gradient.

If those factors are mostly:

- less than 1 → the gradient shrinks repeatedly → it vanishes

- greater than 1 → the gradient grows repeatedly → it explodes

And activations like sigmoid and tanh can make this worse because:

- they saturate

- their slope becomes very small

- the gradient gets dampened even more

So “deeper” doesn’t just mean “more expressive”.

It also means:

more opportunities to dampen the signal.

- after ~10 layers, it’s around one third of its original size

- after ~50 layers, it’s almost gone

- after ~10 layers, it’s a few times bigger

- after ~50 layers, it can become huge and unstable

Exploding Gradients (The Other Failure Mode)

Exploding gradients are the opposite feeling:

- training becomes unstable

- loss can jump around

- weights blow up

- values become huge

- everything becomes sensitive to tiny changes

It’s chaos instead of stagnation.

- Vanishing: looks “calm” but stuck — early layers don’t move.

- Exploding: looks “panicked” — loss jumps, values blow up, training destabilizes.

- Shared root: the learning signal is being repeatedly distorted as it travels through depth.

Why My 2016 Diagnostics Didn’t Catch This

In 2016, I debugged ML models with:

- learning curves

- validation curves

- training vs validation error

Those tools diagnose bias vs variance and help you choose what to do next.

But this month taught me a new category of problem:

And when a deep model isn’t learning, the fixes are different.

Not “add data.” Not “tune lambda.” Not “add polynomial features.”

Instead:

- change activations

- change initialization

- change optimization dynamics

- change architecture assumptions

This was a new mental bucket for me: optimization pathologies.

The “Deep Learning Pattern” I Started Seeing

This month I noticed a repeating pattern in deep learning papers and discussions:

- Someone has a strong model idea

- It doesn’t train

- They discover an engineering fix that makes gradients flow

- Suddenly the model becomes viable and performance jumps

That pattern made breakthroughs like AlexNet feel less like magic and more like:

“We finally found ways to train deep networks reliably.”

It reframed the story.

My Engineering Notes (What I Started Doing Differently)

I didn’t solve vanishing gradients this month. But I changed how I approach deep learning work.

I stopped assuming “more layers” is always better

Depth became a tradeoff:

- expressiveness vs trainability

- more “power” vs more ways to break the learning signal

I started watching gradients like a system metric

Not just loss and accuracy. The learning signal itself.

- if early layers barely change, the model may be “learning” only at the top

I became suspicious of saturation

If an activation flattens out, it’s not just a modeling choice. It’s a training stability risk.

- saturation can make gradients fade even when everything else is correct

In deep learning, many problems are about keeping training dynamics healthy.

What Changed in My Thinking (March Takeaway)

Before March, I thought depth was primarily about representational power.

After March, I realized depth is also a signal propagation problem.

A deep network is not just a bigger model. It’s a deeper chain of transformations that can destroy the gradient.

Understanding that made deep learning feel real.

Not as hype. As engineering.

If gradients don’t make it to the early layers, capacity doesn’t matter.

What’s Next

Next month, I want to learn the first major practical fix that made deep networks viable:

activation functions that don’t kill gradients.

People keep mentioning one name like it’s a turning point:

ReLU.

April is about why that one small change mattered so much.

Activation Functions Are Not a Detail - ReLU Changed Everything

April 2017 — I used to treat activation functions like a minor math choice. Then I saw how one change (ReLU) could decide whether a deep network learns at all.

Backpropagation Demystified - It’s Just the Chain Rule (But Applied Ruthlessly)

Backprop stopped feeling like magic when I treated it like engineering - track shapes, follow the chain rule, and test gradients like you’d test any critical system.