Backpropagation Demystified - It’s Just the Chain Rule (But Applied Ruthlessly)

Backprop stopped feeling like magic when I treated it like engineering - track shapes, follow the chain rule, and test gradients like you’d test any critical system.

Axel Domingues

In January, the perceptron gave me a comforting discovery: neural networks begin in familiar territory. A neuron is basically a weighted sum + an activation. Nothing supernatural.

Then February arrived and immediately removed that comfort.

Because the thing that makes neural networks actually learn is backpropagation.

And backpropagation has a reputation.

People talk about it like it’s a ritual:

- apply some mysterious equations

- wish your shapes line up

- hope the gradients are correct

That’s not how I wanted to learn it.

So I set myself a rule:

This post is the result of trying to make backprop boring.

What you’ll walk away with

A non-mystical mental model of backprop: forward caches, backward signals, per-layer gradients.

What to pay attention to

Backprop fails less from “math” and more from bookkeeping: shapes, element-wise vs matrix ops, bias placement.

How this post is structured

- The claim

- why it feels hard

- graphs

- contracts

- gradient checking

- bugs I hit

The Core Claim

Backpropagation is not a separate algorithm.

It’s the same gradient descent loop I already understood in 2016, but with one difference:

the model is a composition of functions.

So instead of one derivative, I’m computing a chain of derivatives.

That’s it.

The Real Reason Backprop Feels Hard

Backprop isn’t hard because the math is advanced.

It’s hard because you’re doing the same simple operation many times, and one tiny mistake breaks everything.

The pain comes from:

- bookkeeping

- shape mismatches

- mixing element-wise vs matrix operations

- forgetting where the bias term is added

- silently wrong gradients that still “look reasonable”

So I approached it like a software problem:

- break it into interfaces

- validate small pieces

- add checks before trusting the whole

- Loss is NaN/Inf → suspect exploding values, bad initialization, divide-by-zero, or log of 0.

- Loss never changes → suspect a dead activation, wrong learning rate, or gradients not flowing.

- Loss sometimes drops, then stalls → suspect shape mistakes or wrong element-wise vs matrix ops.

- Loss drops but accuracy is nonsense → suspect label encoding / output interpretation mismatch.

A Practical Mental Model: “Credit Assignment”

The cleanest way I found to think about backprop is credit assignment:

“The output was wrong. Who is responsible?”

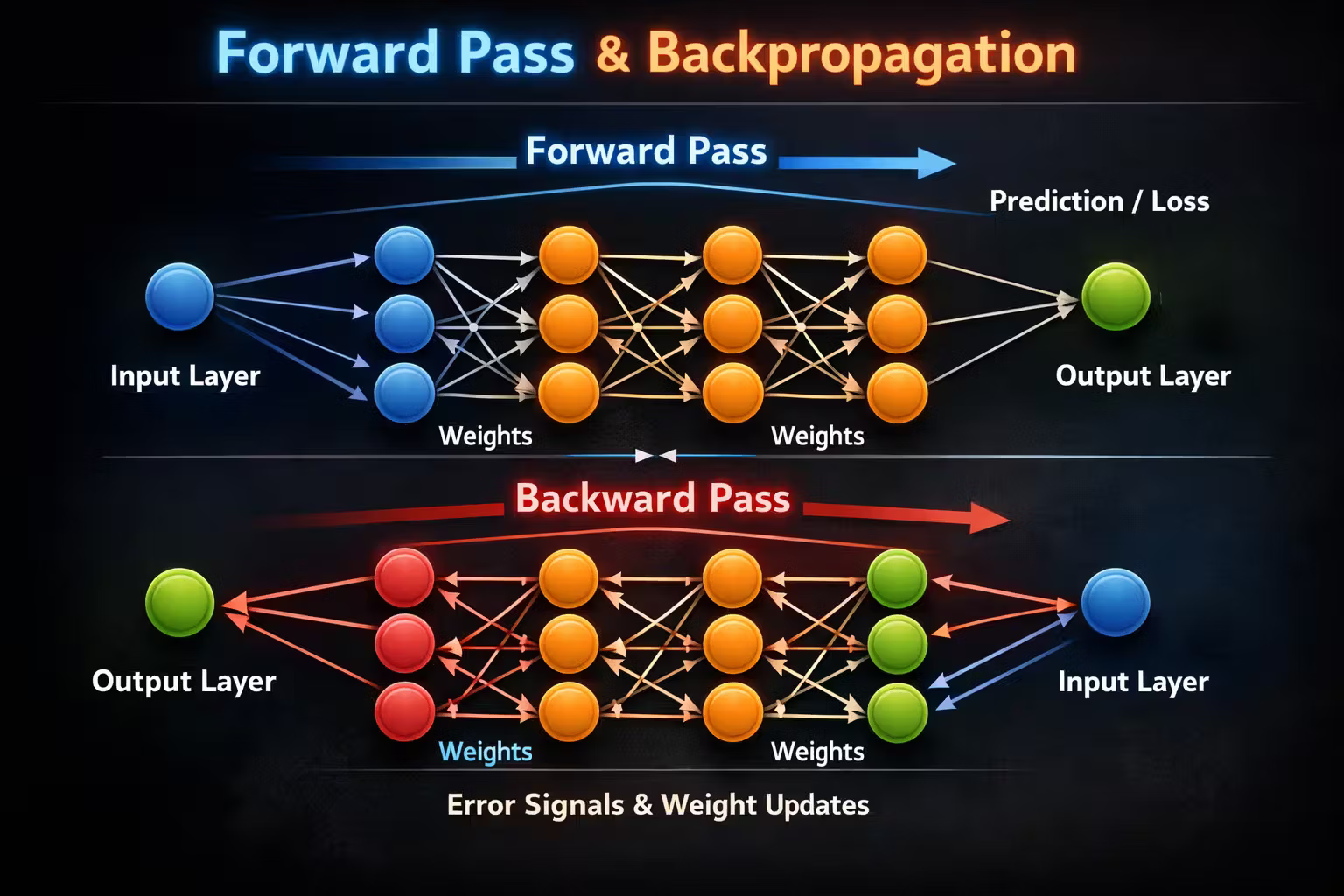

Forward pass:

- compute predictions

Backward pass:

- propagate responsibility backward through the network

Gradients:

- tell each parameter how it should move to reduce error

That framing made it intuitive enough to survive implementation.

Computational Graphs Made This Click

The biggest shift for me this month was seeing neural networks as graphs of computations, not equations.

When you draw it as a graph:

- each node is an operation

- each edge passes values forward

- backprop just sends gradients backward through the same graph

That means you can reason locally:

- each operation knows how to compute its output

- and also how to compute how that output changes with respect to its inputs

Backprop is just repeating that, node by node.

Where the Chain Rule Shows Up (Without Getting Formal)

Here’s the non-mathy version that helped me:

Start from the loss

The loss depends on the final prediction.

Walk one hop backward at a time

Predictions depend on the last layer activations.

Those depend on earlier activations.

Those depend on weights.

Translate the walk into a question

For each weight, ask: “If I nudge this weight slightly, how does the loss react after everything downstream updates?”

So every weight influences the loss indirectly, through everything that happens after it.

Backprop is just computing:

- “how much the loss changes if I change this weight slightly”

but doing it efficiently by reusing intermediate results instead of recomputing everything from scratch.

The Two “Contracts” That Kept Me Sane

When implementing backprop, I kept two contracts in mind.

Contract 1: Every layer produces activations

Forward pass gives me:

- inputs

- intermediate activations

- final predictions

Contract 2: Every layer produces gradients

Backward pass gives me:

- gradients for weights in that layer

- and the “error signal” that must be passed backward

If a layer couldn’t produce those two things, it wasn’t implemented correctly.

The Engineering Habit That Changed Everything: Gradient Checking

Backprop errors are dangerous because they can be subtle.

A wrong gradient can still:

- decrease loss sometimes

- look stable

- appear to “sort of work”

So I leaned heavily on numerical gradient checking — not as a theory trick, but as a debugging tool.

The mindset:

- compute gradients analytically via backprop

- compute gradients numerically by nudging parameters slightly

- compare the two

If they match closely, you can trust your implementation.

This felt like unit tests for ML math.

The Two Bugs I Hit Immediately

1) The bias term mess

Bias units appear in different places depending on your representation. Forgetting to add a bias column at the right time leads to:

- shape mismatches

- or worse: incorrect computations that still run

2) Element-wise vs matrix operations

This is the Octave version of a classic production bug:

- the code runs

- the output is numeric

- everything is wrong

If I accidentally used matrix multiplication where I meant element-wise multiplication (or vice versa), the gradients went off the rails.

I started printing sizes constantly, not as noise, but as a normal practice.

Why My 2016 ML Foundation Helped

In 2016, I spent a lot of time making gradient descent feel intuitive:

- cost bowl intuition

- learning rate sensitivity

- regularization effects

- debugging with learning curves

That foundation mattered because it made one thing obvious:

backprop is not the learning algorithm. Gradient descent is.

Backprop is just the machinery that produces gradients for gradient descent.

Once I understood that separation, it stopped feeling like a dark art.

What Changed in My Thinking (February Takeaway)

Before this month, “backprop” sounded like something you either memorized or avoided.

After this month, it became something much simpler:

Backprop is the chain rule turned into an efficient engineering procedure.

Not glamorous. Not mystical. Just extremely sensitive to implementation details.

And that realization gave me confidence — because now I can debug it like software.

What’s Next

Next month I want to understand why deep networks are hard to train even when backprop is correct.

I keep hearing the same phrase:

vanishing gradients

I now know what gradients are and how they flow.

March is about understanding what happens when they don’t.

Why Deeper Networks Are Harder to Train Than I Expected

I assumed “more layers” would just mean “more power.” Instead I discovered that depth introduces a new failure mode - gradients can disappear (or explode) long before the model learns anything useful.

From Logistic Regression to Neurons - Rebuilding Intuition from the Perceptron

After finishing Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning course, I start my deep learning journey by revisiting the perceptron and realizing neural networks begin with ideas I already understand.