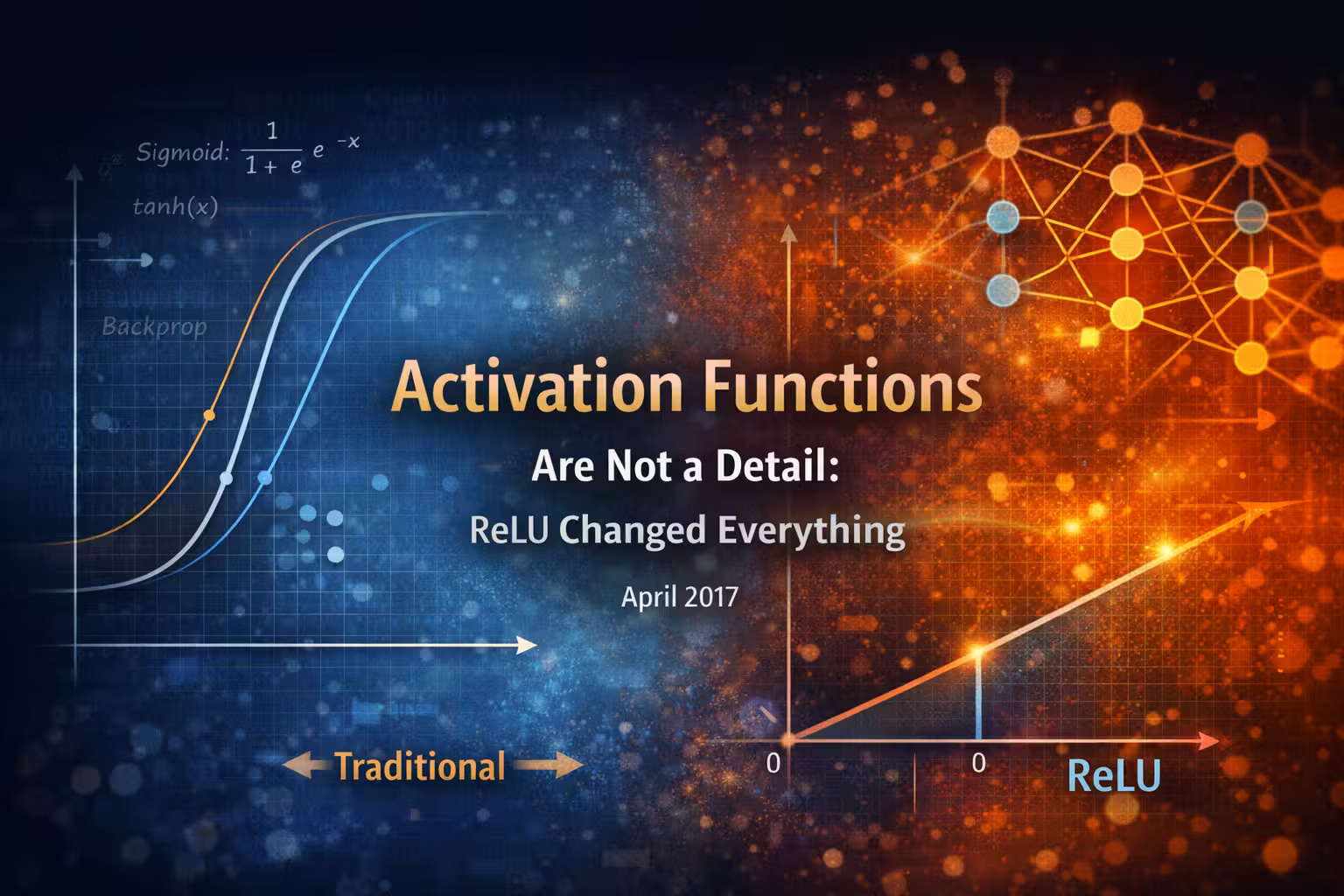

Activation Functions Are Not a Detail - ReLU Changed Everything

April 2017 — I used to treat activation functions like a minor math choice. Then I saw how one change (ReLU) could decide whether a deep network learns at all.

Axel Domingues

March was the first month where deep learning stopped feeling like “a bigger version of ML” and started feeling like its own discipline.

I learned a hard truth:

A deep model can be correct, expressive, and theoretically powerful — and still fail to learn anything useful.

Most of that pain showed up as gradients that either vanished quietly or exploded noisily.

So April was about looking for the first practical fix.

And I kept seeing the same thing mentioned everywhere:

ReLU.

At first I was skeptical. An activation function? Really?

In 2016, activation functions felt like a detail. Logistic regression had a sigmoid. Neural nets had sigmoid or tanh. End of story.

April taught me that activation functions are not a detail.

They’re infrastructure.

What you’ll learn

Why activation functions are not “just a curve”, and how one choice can decide whether a deep model trains at all.

The key mental model

Activations don’t only shape outputs — they shape the learning signal (gradients) flowing backward from the loss.

Practical takeaway

You’ll leave with a simple debug lens: “Is my activation helping gradients survive depth?”

Why Activations Felt Like a Detail (My 2016 Bias)

Coming from classical ML, I had a very stable mental model:

- you choose an objective (loss)

- you choose a model family

- you optimize

- you regularize

- you diagnose bias vs variance

- Activation: a function applied inside each neuron after the weighted sum.

- Gradient / learning signal: the “how to change” message that flows backward from the loss during backprop.

- Saturation: when an activation becomes flat in a region, reducing useful gradient flow.

- Trainability: whether optimization can reliably update early layers enough to learn.

- Dead ReLU: a ReLU unit that outputs 0 almost always and effectively stops updating.

Activations looked like “just a curve” inside the model.

But deep networks exposed a new dependency:

It shapes the learning signal that must travel through the network.

Forward pass is the “prediction pipeline”

Activations shape what the network can represent.

Backward pass is the “learning pipeline”

Gradients flow from the loss back toward earlier layers.

Activations sit in both pipelines

So an activation can be “expressive enough” and still make training fail by weakening the learning signal.

If the activation crushes gradients, training collapses.

So the activation function is not only about expressiveness.

It’s also about trainability.

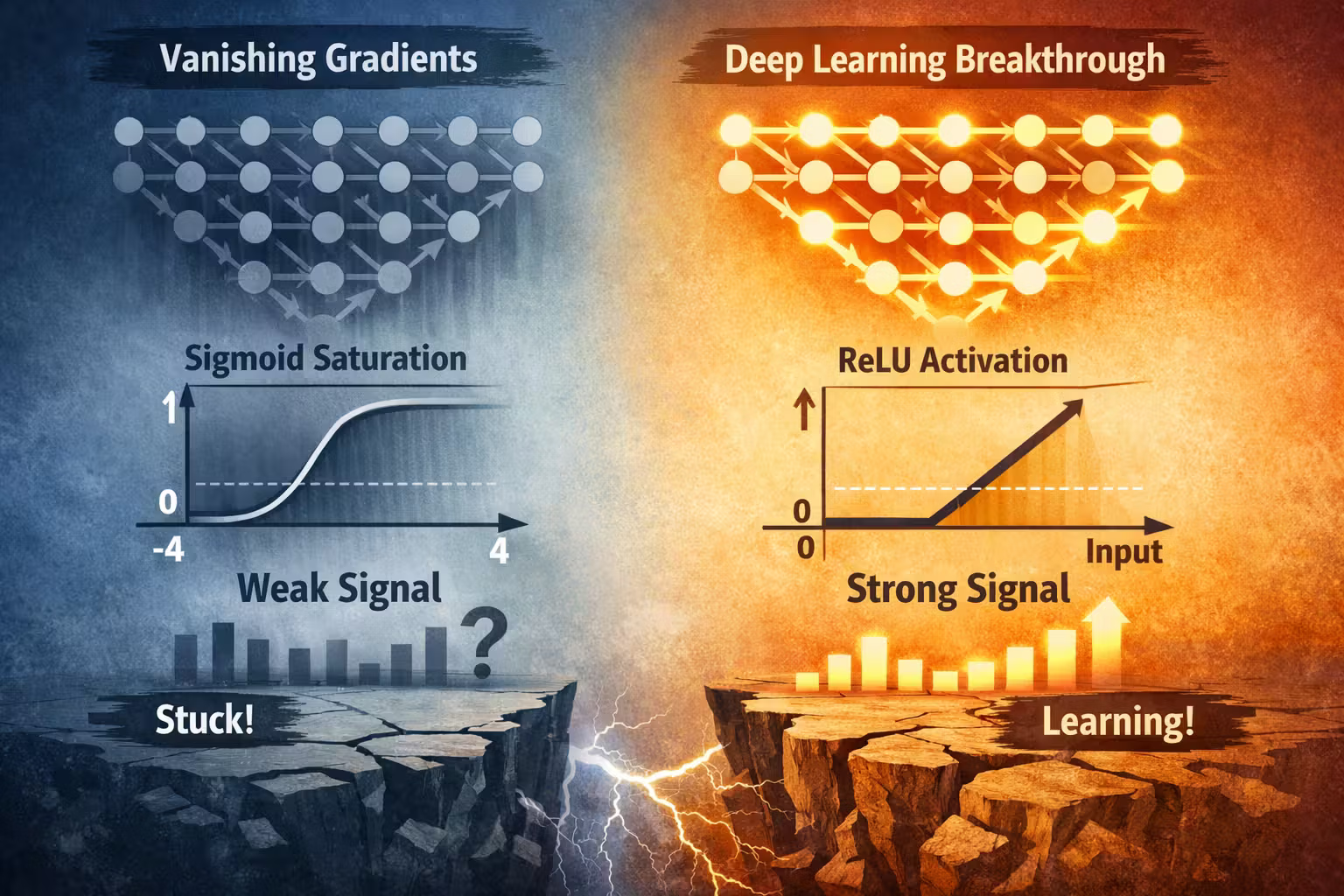

The Problem with Sigmoid (In Practice)

Sigmoid is intuitive:

- it outputs values between 0 and 1

- it feels like probability

- it’s smooth and stable

But when I tried to imagine a deep stack of sigmoid activations, I kept running into the same behavior:

- for large positive or negative inputs, sigmoid saturates

- when it saturates, its slope becomes tiny

- tiny slope means tiny gradients

- tiny gradients multiplied across many layers become basically zero

So even if backprop is correct, the early layers get almost no learning signal.

- training runs but barely improves

- early layers change very slowly

- you keep tweaking learning rate and nothing really “wakes up”

One slightly-shrunk learning signal isn’t a disaster.

But deep nets repeat that shrinkage many times, until early layers effectively hear silence.

- Are early-layer weights changing at all?

- Do activations spend lots of time in “flat” regions?

- Do gradients look tiny near the input side?

March explained the problem. April made me understand why ReLU was a turning point.

ReLU: The Smallest Change With the Biggest Impact

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) is almost embarrassingly simple:

- if the input is negative → output 0

- if the input is positive → output the input

That’s it.

Why it helped

For positive inputs, ReLU avoids constant squashing — the learning signal can stay usable through depth.

Why it surprised me

It’s not “fancier math.” It’s a training-dynamics fix.

What changed in my framing

I stopped asking “is it expressive?” first — and started asking “does it train reliably?”

No curve fitting. No probability interpretation. No smooth “S-shape”.

At first it felt too simple to be meaningful.

Then I realized the key property:

This matters enormously in deep networks.

Because the biggest problem I had in March wasn’t expressiveness.

It was signal preservation.

ReLU is a signal-preserving activation for the region where the neuron is “active”.

The “Deep Learning” Reframe That Happened Here

This month I started seeing deep learning differently:

- classical ML feels like: “choose the right model + objective”

- deep learning feels like: “keep training dynamics healthy long enough for learning to happen”

Classical ML mindset

Choose the right objective + model family, then optimize and regularize.

Deep learning mindset

Keep training dynamics healthy long enough for learning to happen (signal flow, stability, initialization).

That shift explains why deep learning breakthroughs often look like:

- architecture changes

- activation changes

- initialization changes

- optimization changes

Not because the objective is new.

But because training deep networks is fragile.

The Catch: “Dead ReLUs”

ReLU isn’t free.

There’s a failure mode I ran into quickly in my reading and experiments:

If a neuron’s input stays negative, its output becomes 0. If its output becomes 0 consistently, the gradient through it can effectively disappear. Then it stops updating.

People call this a “dead ReLU”.

- a large fraction of activations are exactly 0 most of the time

- some neurons never “turn on” across many batches

- parts of the network stop contributing and stop improving

- weights/biases push inputs negative too often

- learning rate too aggressive early on

- unlucky initialization combined with certain data scaling

- verify input scaling

- reduce learning rate if training is unstable

- consider ReLU variants that reduce “dying” risk (if you introduce them later)

So ReLU trades one kind of problem (saturation everywhere) for another (units can die).

But the trade is worth it, because:

- many neurons remain active

- gradients remain healthy through active paths

- deep networks become trainable

Why ReLU Fits the “Engineering Lens”

I started appreciating ReLU not as a mathematical choice, but as an engineering choice:

- cheap to compute

- gradient-friendly

- avoids the constant saturation problem of sigmoid/tanh

- scales better with depth

It’s a practical fix to a real system constraint: gradients must remain usable.

That mindset felt similar to things I learned in 2016:

- feature scaling

- choosing learning rates

- regularization tradeoffs

But this was deeper — literally.

How This Connects Back to 2016 ML Concepts

This month made me revisit a familiar idea from 2016:

the optimization landscape matters.

In the ML course, I learned:

- gradient descent depends on cost surface shape

- scaling changes convergence

- regularization changes the objective

In deep learning, activation functions also shape the landscape — not only the function you can represent, but how gradients behave across layers.

So the continuity was there:

- it’s still optimization

- it’s still gradients

- it’s still stability

But now the model’s internal design choices actively affect whether optimization works at all.

What I Changed in My Workflow (April Edition)

Even without a full deep learning framework, my thinking shifted:

- I stopped treating activations as defaults

- I started asking: “What does this do to gradient flow?”

- I started viewing deep learning as a system with failure modes, not a formula to apply

That is a huge mental shift.

What Changed in My Thinking (April Takeaway)

Before April, I thought activation functions were mostly about shaping outputs.

After April, I understood the deeper truth:

Activation functions are about whether learning is possible at all.

ReLU didn’t just improve performance.

It made depth practical.

What’s Next

ReLU helped gradients survive, but it doesn’t solve everything.

Next month I’m focusing on another silent factor that decides whether deep training behaves:

initialization.

In classical ML, starting weights rarely mattered much.

In deep networks, the starting point can decide whether the whole system learns or collapses.

May is about that fragility — and how people started engineering around it.

Initialization, Scale, and the Fragility of Deep Networks

After learning why gradients vanish, I discovered something even more unsettling - deep networks can fail before training even begins, simply because the starting scale is wrong.

Why Deeper Networks Are Harder to Train Than I Expected

I assumed “more layers” would just mean “more power.” Instead I discovered that depth introduces a new failure mode - gradients can disappear (or explode) long before the model learns anything useful.