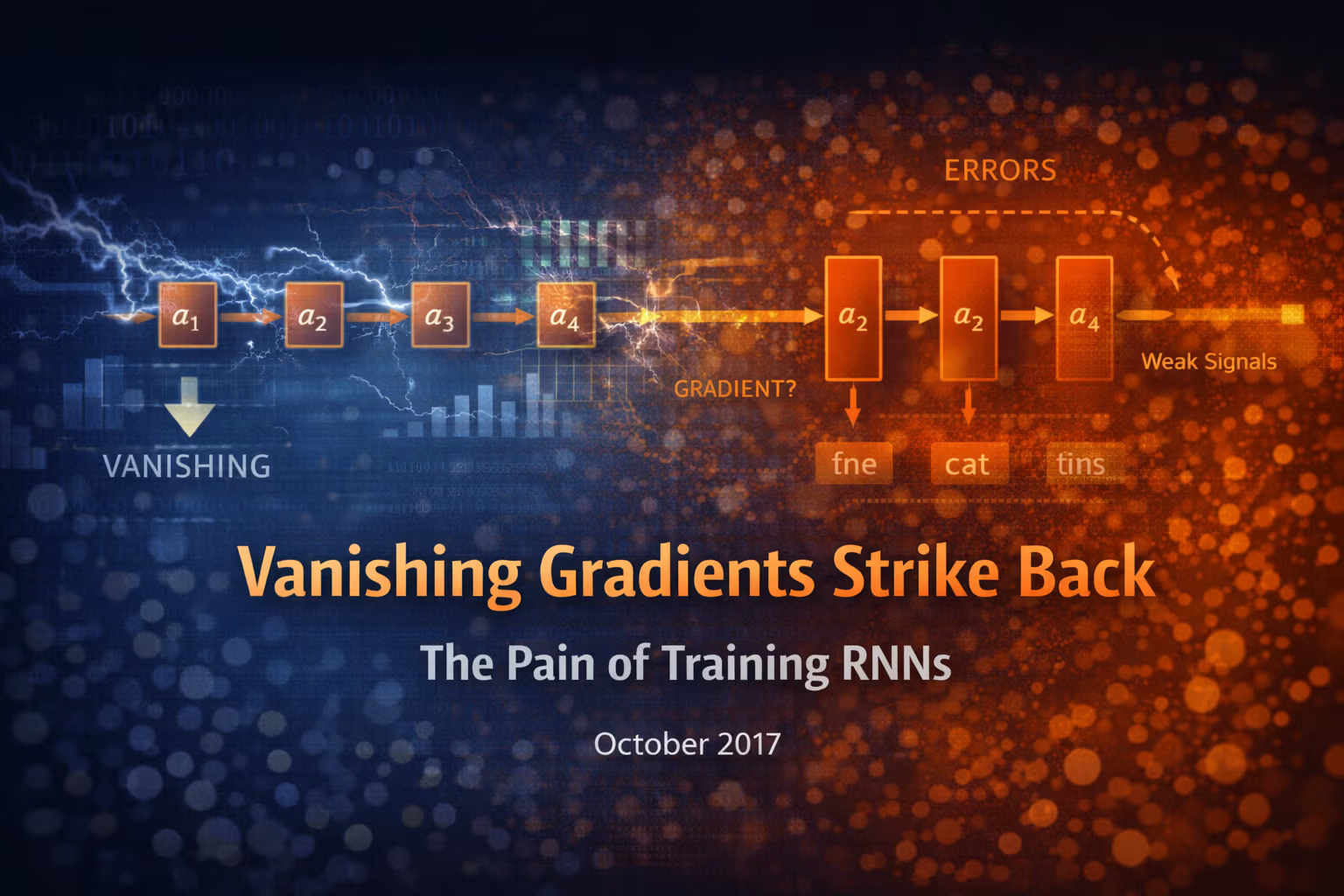

Vanishing Gradients Strike Back - The Pain of Training RNNs

RNNs looked elegant on paper. Training them exposed the same old enemy—vanishing/exploding gradients—just with “depth in time”.

Axel Domingues

Last month, I finally understood what an RNN is:

- a shared-weight cell

- unrolled across time

- producing a hidden state that acts like learned memory

This month, I learned what an RNN does to you:

It turns training into a fight with gradients.

And not in a theoretical way. In a “my loss is NaN” way.

What this post explains

Why vanilla RNNs reintroduce vanishing/exploding gradients via depth in time.

The 3 failure patterns

- learns short-term only

- sudden instability / NaNs

- tiny hyperparameter changes feel dramatic

The practical toolkit

Instrumentation + gradient clipping + sequence-length curriculum + cautious learning rate.

The Problem: Depth in Time Is Still Depth

In March I wrote about why deeper networks were harder to train than I expected.

October felt like that lesson returning… with a twist.

Because with RNNs, you can have a network that is shallow in layers, but extremely deep in time:

- 1 recurrent layer

- unrolled for 100 steps

- behaves like a 100-layer deep computation graph (with shared weights)

So all the trouble we saw in deep feedforward nets shows up again:

- gradients shrink until nothing learns

- gradients explode until everything breaks

Just… now it’s happening through time.

Once I accepted that, RNN training stopped feeling “mysterious” and started feeling like a predictable failure mode with a checklist.

- Unrolling: rewriting the RNN loop as repeated steps (t1..tT).

- Depth in time: the unrolled chain behaves like a deep computation graph.

- Hidden state: the running summary passed forward through time steps.

- Gradient flow: learning signal flowing backward from loss → earlier time steps.

- Norm: a simple “magnitude” number (useful for spotting blow-ups or collapse).

What I Observed First (Before I Understood Why)

I ran a simple character-level RNN again, but pushed it slightly harder:

- longer sequences

- slightly larger hidden state

- more training steps

And I saw three recurring behaviors:

- The model learns short-term patterns but ignores long-term ones

- Training becomes unstable: loss spikes suddenly

- Changing tiny hyperparameters feels like switching realities

Symptom

Learns local structure, but long context doesn’t improve.

Symptom

Training looks fine… then suddenly spikes and collapses.

Symptom

Small changes in hyperparameters produce totally different outcomes.

At first this looked like randomness.

Then I realized it was the same underlying issue:

Gradient flow across long chains is fragile.

First checks:

- increase sequence length and see if learning degrades sharply

- log gradient magnitude vs time step (earlier steps often get almost nothing) First move:

- shorten sequences for sanity runs, then increase gradually

First checks:

- gradient norm spikes just before failure

- hidden state norm grows within a sequence First move:

- enable gradient clipping

- reduce learning rate if spikes persist

First checks:

- are you right on the edge of instability?

- do norms vary dramatically run-to-run? First move:

- lower learning rate and add clipping to make behavior more predictable

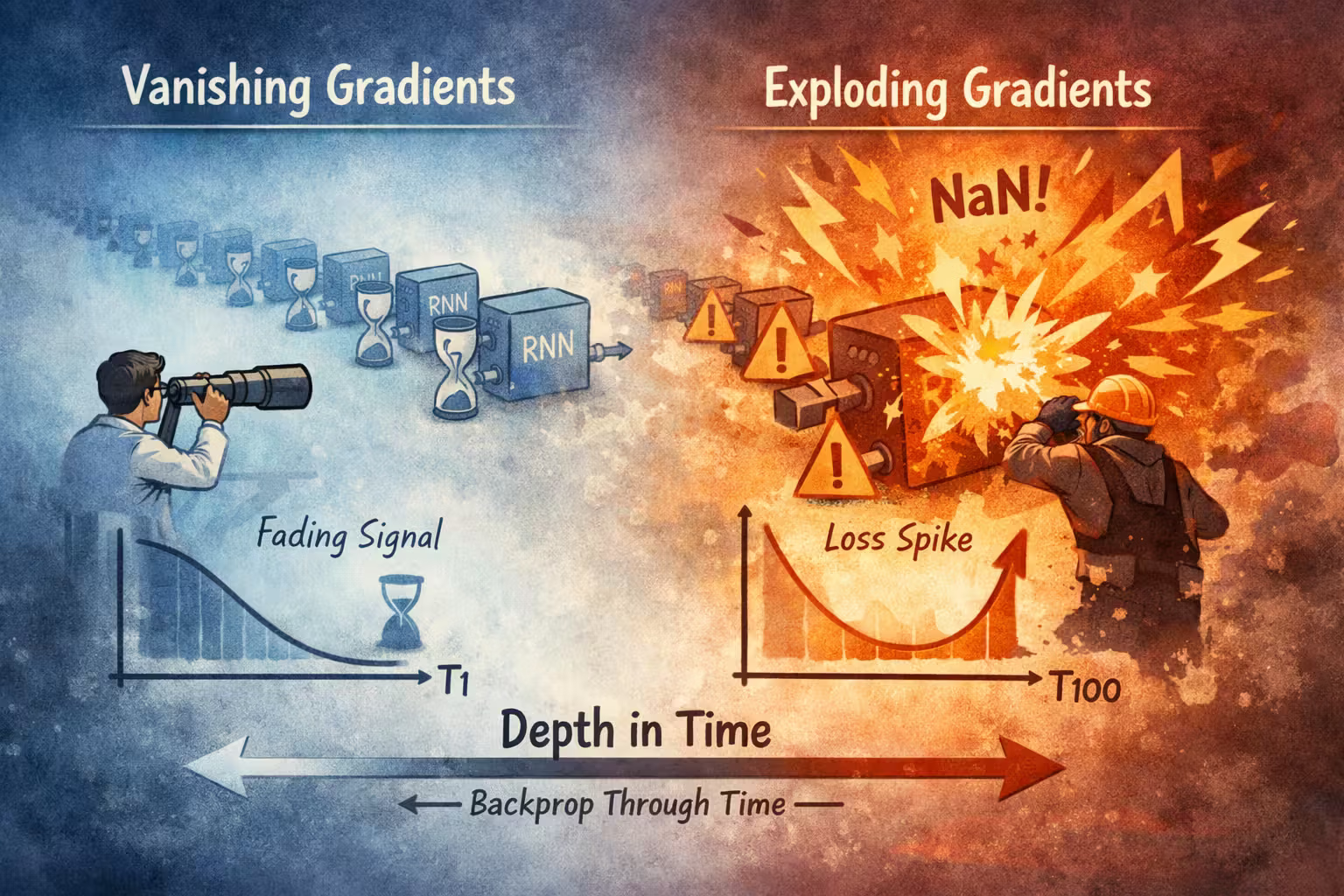

Vanishing Gradients: When Learning Can’t Reach the Past

Here’s how it felt in practice:

- early in training, the RNN becomes decent at local structure

- it predicts plausible next characters for short contexts

- but it fails at anything requiring a long memory

The key symptom:

Improvements in prediction happen mostly for nearby dependencies.

It’s like the network can only “hear” the last few time steps.

Everything earlier becomes muffled.

Train on a short sequence length where it clearly improves, then increase length. If learning quality collapses as length grows (with the same code), you’ve learned something real: the backward signal from the loss isn’t reaching early time steps reliably.

My mental model (no math, just intuition)

Every time step applies another transformation to the signal (forward) and to the gradient (backward).

If that transformation tends to shrink values, then after enough steps:

- hidden state forgets

- gradients fade

- early time steps get almost no learning signal

So the network may technically “have memory” — but training never teaches it to use it.

When I trained on short sequences, learning looked fine. When I trained on long sequences, the “same code” suddenly stopped learning. That length sensitivity is a huge clue.

Exploding Gradients: When One Bad Update Destroys the Run

The other failure was more dramatic.

Everything looks fine… then:

- loss jumps by an order of magnitude

- weights become huge

- hidden state norms blow up

- the next update produces NaNs

This felt like training “falls off a cliff”.

And the mechanism is the same story in reverse:

If a transformation tends to amplify values, repeated over many steps it can turn small numbers into huge ones.

What it looked like in my logs

- hidden state norm grows steadily during a batch

- gradient norm spikes

- loss spikes right after

- and training becomes unrecoverable

In classical ML I almost never saw “catastrophic training collapse.”

Here it was… normal.

You’ll think your implementation is wrong.

- Sometimes it is.

- But often it’s not.

- Sometimes it’s just that RNN optimization is fragile by nature.

The Engineering Response: Instrument Everything

My 2016 “treat it like a system” mindset saved me here.

Instead of guessing, I added instrumentation.

What I tracked

- loss per iteration

- hidden state norm (average and max across time)

- gradient norm (approximate is fine)

- how these values change as I increase sequence length

If I can’t see the signals, I can’t reason about the failure.

- per-iteration: loss

- per-batch: gradient norm (rough magnitude)

- per-sequence: hidden-state norm over time steps (watch for drift)

- per-experiment: compare these as you change sequence length

The Practical Fixes I Used (And Why They Help)

I didn’t want to jump straight to LSTMs yet.

I wanted to understand what you can do with a “vanilla” RNN first.

Here’s the short list that actually made my runs survivable.

Clip gradients (the first lifesaver)

When gradients explode, clip them to a maximum norm.

This doesn’t fix learning long-term dependencies, but it prevents training from collapsing.

Keep sequences shorter during early experimentation

I started training on shorter sequences just to validate learning, then gradually increased the length.

This made debugging possible.

Reduce the learning rate when instability appears

Exploding gradients get worse with aggressive steps.

A smaller learning rate made training slower, but less chaotic.

Use momentum carefully (or turn it off temporarily)

Momentum can accelerate learning, but it can also amplify instability in fragile settings.

For debugging, I often started with plain SGD and only added momentum later.

It turned RNN training from “randomly catastrophic” into “predictably difficult.”Gradient clipping.

Why Long-Term Dependencies Are So Hard (In Plain Words)

I kept trying to get the vanilla RNN to remember a detail from far back in a sequence.

And it clicked that the network isn’t failing because it’s dumb.

It’s failing because the training signal has to travel through too many transformations.

Even if the architecture could represent the dependency, the optimizer can’t reliably deliver learning to the earlier steps.

This was the crucial realization:

Architecture and optimization are inseparable.

You can’t talk about “sequence modeling” without talking about gradient flow.

How This Connected Back to My 2016 Foundation

This month didn’t feel like “new ML”.

It felt like the same fundamentals—just under more stress:

- Optimization: gradient descent is still the engine, but now it’s unstable

- Diagnostics: you must instrument and interpret failure modes

- Regularization mindset: constraints can stabilize learning

- System thinking: treat training like a process you can observe and debug

It also echoed CNNs:

CNNs succeed partly because their structure improves learnability.

RNNs struggle partly because their structure makes learnability harder.

Same principle, opposite outcome.

What Changed in My Thinking (October Takeaway)

I used to think:

“If the model is expressive enough, training will figure it out.”

After this month I think:

Expressiveness doesn’t matter if gradients can’t deliver learning to where it’s needed.

Depth in time is not “just another dimension.”

It’s a multiplier on optimization pain.

What’s Next

Vanilla RNNs taught me the problem.

Now I want the engineering solution that made sequence modeling practical:

LSTMs: Engineering Memory into the Network

Gates, memory cells, and a design that’s basically built to keep gradients alive.

FAQ

No. I saw it earlier with deep feedforward nets too. RNNs just make it unavoidable because unrolling creates deep chains through time, even with only one recurrent layer.

Gradient clipping. It doesn’t solve long-term memory, but it prevents exploding gradients from destroying training runs.

They’re still great for building intuition. They show exactly what breaks, and that makes LSTMs feel like a purposeful engineering response instead of a magical upgrade.

LSTMs - Engineering Memory into the Network

After vanilla RNNs taught me why gradients collapse through time, LSTMs finally felt like an engineered solution - keep the memory path stable, and control it with gates.

Why Sequences Break Everything - Enter Recurrent Neural Networks

Images were hard, but at least they were static. Sequences add “time”, shared weights, and state — and suddenly the assumptions I relied on in 2016 stop holding.