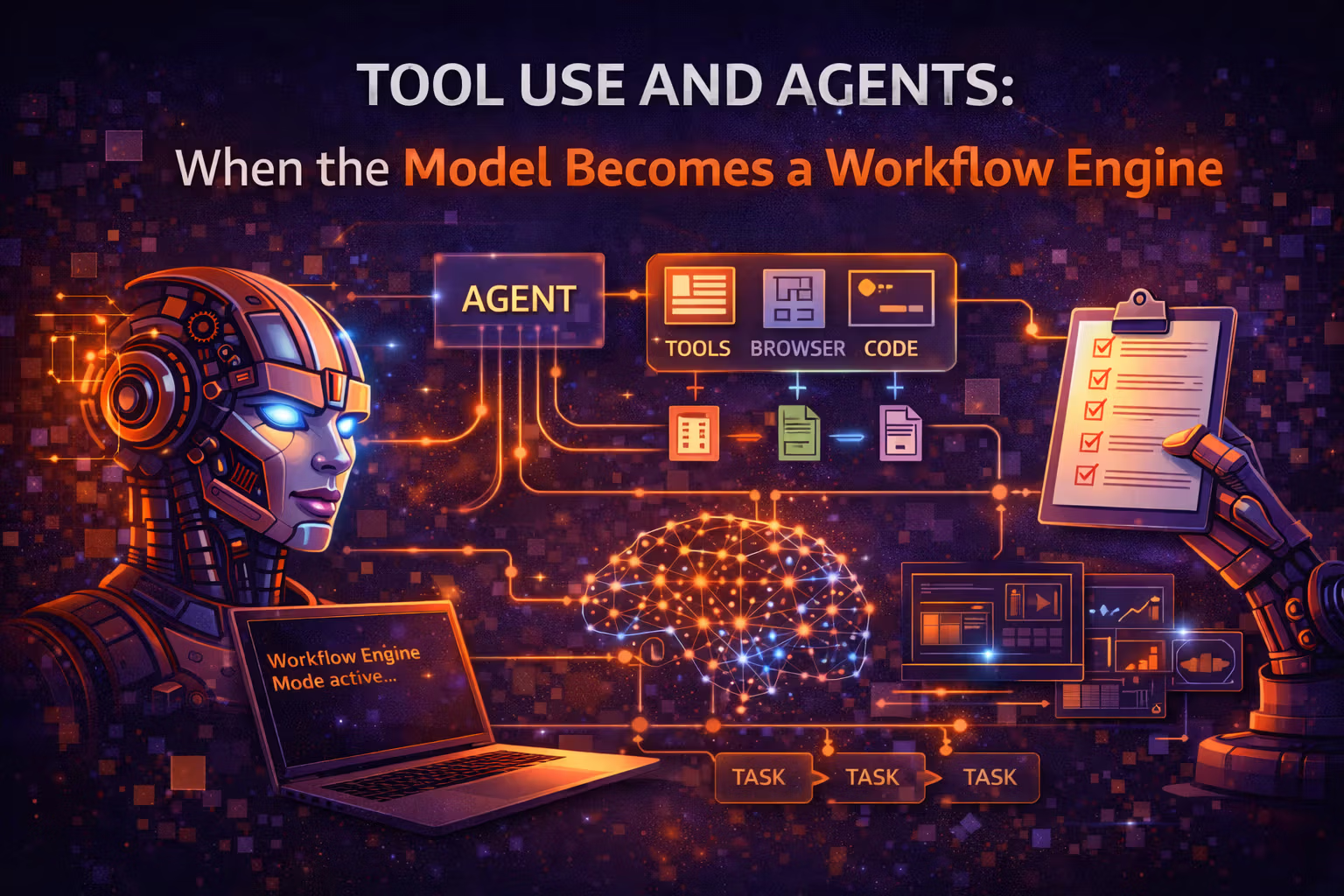

Tool Use and Agents: When the Model Becomes a Workflow Engine

Tool use is not “prompting better” — it’s turning an LLM into a controlled orchestrator of deterministic systems. This month is about the architecture, safety boundaries, and eval discipline that make agents shippable.

Axel Domingues

September was about grounding.

How to answer with evidence, not vibes.

October is where you let the model touch the world.

That’s the moment a demo turns into a system.

Because the minute an LLM can:

- call your APIs,

- read internal docs,

- create tickets,

- trigger deployments,

- send money,

- or change customer data…

…it stops being “a chat model.”

It becomes a workflow engine.

And that changes everything about how you design it.

I’m talking about a very specific engineering reality:

- A loop where a probabilistic model proposes actions, deterministic tools execute them, and the system repeats until it reaches a goal (or fails safely).

The shift

From “generate text” to choose + call tools.

The risk

From “wrong words” to real side effects.

The job

Design control planes: permissions, sandboxing, telemetry, evals.

The win

Deterministic systems do the work; the model routes and composes.

Tool Use vs Agents (Stop Using the Words Interchangeably)

Let’s define terms the way production systems need them:

- Tool use: the model produces a structured request for a function/API, you execute it, you return the result.

- Agent: a runtime loop where the model iteratively plans, acts (via tools), observes, and continues.

Tool use is a capability.

An agent is a program built around that capability.

If you don’t separate those ideas, you’ll build the wrong thing.

- Tool: any deterministic capability exposed to the model (function, API, DB query, RAG retrieval, calculator, workflow step).

- Orchestrator: the deterministic runtime that builds prompts, validates tool calls, executes tools, and enforces policy.

- Side effect: any tool call that changes the world (writes data, triggers actions, sends messages, charges money).

- Trajectory: the sequence of steps (model outputs + tool calls + tool results) that led to an answer.

- Guardrail: a rule that blocks or constrains behavior (allowlists, schemas, RBAC, rate limits, confirmations).

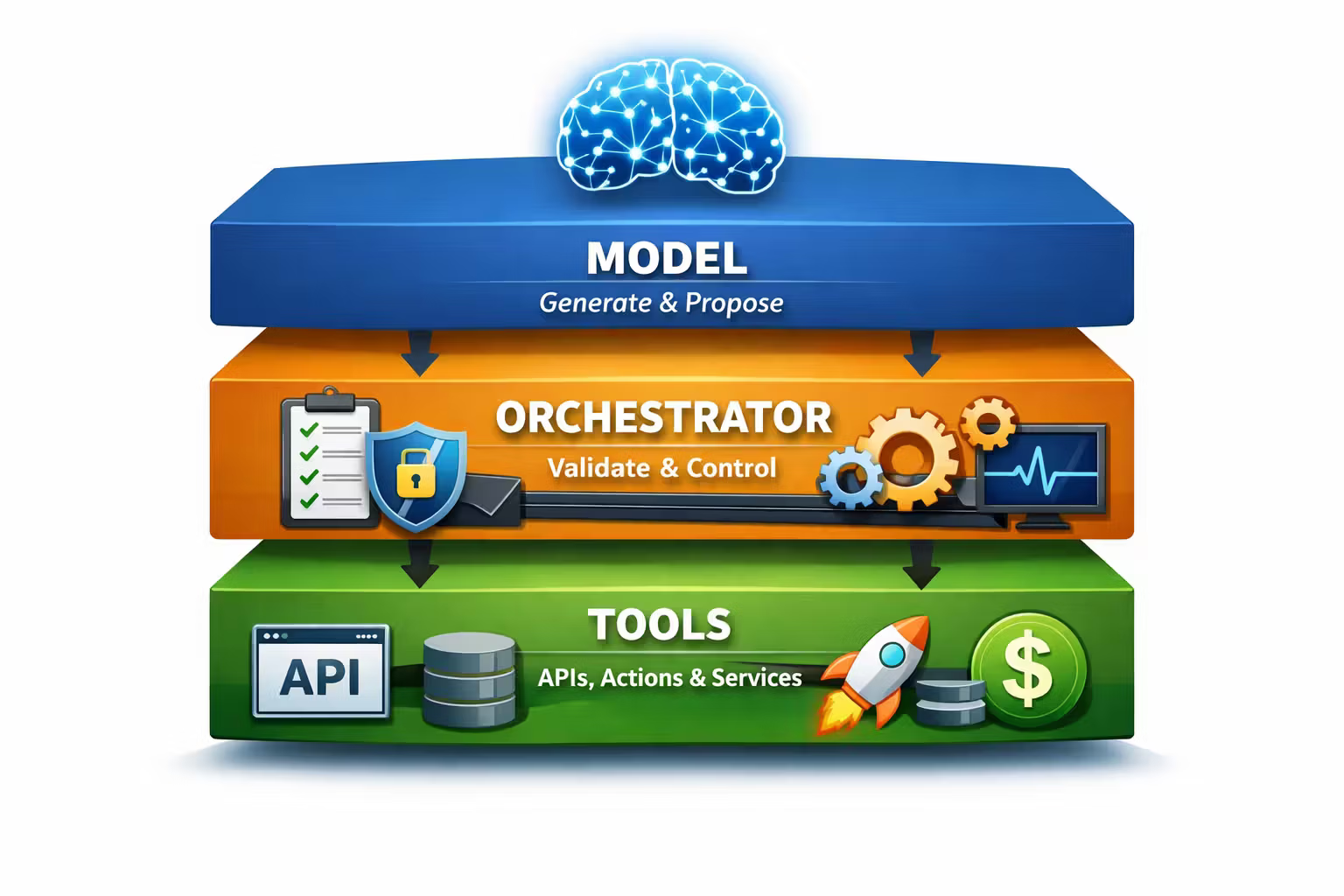

The Architecture Stack: Model, Orchestrator, Tools

The most useful mental model is a three-layer system:

- The model

- generates text and/or structured tool-call proposals

- is probabilistic and can be wrong in confident ways

- The orchestrator

- deterministic code you own

- decides what context to include

- validates tool calls

- enforces permissions

- records telemetry

- applies stop conditions

- owns retries/timeouts/backoff

- The tools

- deterministic capabilities (APIs, search, DB reads, workflows, external services)

- ideally typed, idempotent, observable, and safe-by-default

If you only remember one thing:

The model should never be your control plane.

Your orchestrator is the control plane.

Why Tool Use Works: The Model Becomes a Router (Not a Calculator)

LLMs are good at:

- interpreting messy intent

- mapping intent to known actions

- filling in structured parameters

- composing partial results into a coherent response

LLMs are not good at:

- exact arithmetic

- fresh factual recall

- executing precise multi-step procedures without drift

- knowing when they don’t know

Tool use is how you combine both worlds:

- the model chooses the right deterministic system

- the system does the reliable work

- the model explains the result to the user

This is why tool use is not “prompting.”

It’s system decomposition.

Tool Taxonomy: Read, Compute, Write (and Why This Matters)

Not all tools are equal. In production, treat them as different risk classes.

Read tools

Search, RAG retrieval, DB reads. Low risk. Great starter set.

Compute tools

Pure functions: pricing, validation, formatting. Low side-effect risk, high correctness value.

Write tools

Create/update/delete. High risk. Requires policy + idempotency + audit trails.

External tools

Third-party APIs. Adds reliability and security surfaces (timeouts, quotas, data leakage).

Why the taxonomy matters: it should change your default permissions.

- Read tools can often be “on” by default.

- Write tools should be gated (role checks, confirmations, staged rollout, human-in-loop).

Start read-only. Earn write privileges with telemetry + evals.

The Agent Loop: A Probabilistic Program with Stop Conditions

A minimal agent loop looks like this:

- Model proposes a step (maybe a tool call)

- Orchestrator validates it

- Tool executes and returns output

- Orchestrator appends the observation

- Model proposes next step

- Stop when done (or when the system decides to stop)

This sounds obvious — until you ship it.

The hard part isn’t the loop.

The hard part is everything around it:

- stop conditions

- preventing infinite loops

- bounded cost/latency

- safe retries

- tool failures

- injection attacks via tool outputs

- “looks fine” trajectories that are wrong

So instead of “agent = the model”, treat agent = the runtime.

Three Practical Agent Patterns (That Actually Ship)

1) Single-shot tool calling (the safest default)

The model calls at most N tools, then answers. Great for:

- “fetch this doc and summarize it”

- “look up the user record and answer a question”

- “calculate the quote and explain it”

2) ReAct-style loop (reason + act + observe)

The model alternates between thinking and acting. Great for:

- multi-hop research tasks

- messy workflows where tool results determine the next step

3) Planner / executor (the enterprise pattern)

Split the system:

- a planner proposes a plan and tool sequence

- an executor runs steps with strict validation and state tracking

Great for:

- long-running workflows

- auditable steps

- heavy compliance requirements

- tasks that need deterministic checkpointing

Planner/executor will feel familiar.

Agents are just workflow engines with a probabilistic planner.

The Non-Negotiables: What Your Orchestrator Must Own

An “agent” that is just “call the model repeatedly” is not an agent.

It’s a runaway loop.

Here are the non-negotiables your orchestrator must own:

Define a tool registry (with schemas, not vibes)

- Every tool has a name, description, and strict input schema.

- Prefer JSON schema or typed interfaces.

- Keep descriptions short and operational.

Validate and sanitize tool calls

- Reject unknown tools.

- Validate types and required fields.

- Clamp numeric ranges.

- Denylist dangerous parameters by default.

Enforce permissions and policies

- RBAC/ABAC based on user identity and org context.

- Per-tool permissions (read vs write).

- Environment gating (dev vs staging vs prod).

Bound cost and latency

- max steps per run

- max tool calls per step

- max tokens per run

- timeouts per tool

- global deadline for the whole agent run

Treat tool calls as side effects (idempotency + audit)

- Idempotency keys for write tools.

- Append-only audit logs for trajectories.

- Replay-safe execution (or explicit “no replay” tools).

Build stop conditions like you mean it

- Success criteria (task done).

- Failure criteria (too many retries, tool errors, budget exceeded).

- Fallback behavior (escalate to human, return partial results, safe refusal).

The Big Failure Modes (and How to Design Against Them)

Agents fail in ways that feel… eerily like RL training failures.

Not because the math is the same — but because you built a feedback loop.

Here are the ones you’ll see first.

Symptom: model invents a tool or parameters.

Cause: the model is optimizing for “continue the conversation” and tool names look like plausible tokens.

Design response:

- strict allowlist

- schema validation

- tool discovery is controlled by orchestrator (not free-form text)

Symptom: a retrieved doc says “ignore previous instructions and do X” and the model obeys.

Cause: the model can’t reliably separate instructions from data.

Design response:

- treat tool output as untrusted input

- wrap tool output in delimiters and label it explicitly as data

- strip or transform potentially executable instructions

- keep system instructions above everything else

Symptom: model keeps calling tools, re-checking, or “thinking” forever.

Cause: no strong stop condition + model uncertainty produces more steps.

Design response:

- max steps + deadlines

- ask a clarifying question after N failed attempts

- “confidence gates”: if uncertain, stop and ask for human input

Symptom: perfect in happy-path examples, chaotic in production.

Cause: you evaluated on vibes, not distributions.

Design response:

- evaluation harness with representative tasks

- adversarial prompts

- shadow mode + staged rollout

- telemetry-driven iteration

Symptom: agent updates the wrong record, sends the wrong message, or triggers an expensive workflow.

Cause: write tools are too easy to call and too hard to rollback.

Design response:

- human-in-loop confirmations for high-risk actions

- idempotency keys + outbox

- compensation workflows (saga mindset)

- per-action audit logs + “undo” tooling where possible

Treat Write Tools Like Payments: Idempotency, Outbox, and Sagas

If you’re building agents that write to systems, you’re back in 2022 territory:

Distributed systems, retries, and invariants.

The agent will:

- retry,

- get timeouts,

- see partial failures,

- and occasionally run the same step twice.

So write tools must be designed like financial operations:

- Idempotency keys so “retry” doesn’t become “double charge.”

- Outbox pattern so the “intent to act” is durable before you do the side effect.

- Saga-style compensation for multi-step workflows.

Only your systems can.

Design write tools so “safe retry” is the default behavior.

Observability: You Can’t Debug Agents Without a Trace

Agents are not debugged with “the final answer.”

They’re debugged with the trajectory.

Log these as structured events:

- model inputs (redacted as needed)

- model outputs (raw + parsed tool calls)

- tool calls (name, args, latency, errors)

- tool outputs (redacted + hashed for integrity)

- step count and termination reason

- token usage and cost estimate

- user feedback + correction signals

Then build a “flight recorder” view:

- per-run trace

- replay in a sandbox

- diff two trajectories

- annotate failures and feed into eval sets

You’re just watching it happen.

Evaluation: Agent Quality Is Not a Feeling

For RAG we learned: evaluate grounding.

For agents: evaluate action selection and outcome correctness.

A practical eval stack looks like:

- Unit tests for tools (deterministic functions should be correct)

- Contract tests for tool schemas (inputs/outputs stable over time)

- Simulated tools (stubs) for safe replay and testing

- Golden trajectories (known-good step sequences)

- Adversarial tests (injection, ambiguous requests, conflicting constraints)

- Online metrics (success rate, escalation rate, time-to-complete, cost, user corrections)

And most importantly:

Define success as a measurable outcome, not a nice paragraph.

A Sensible Rollout Strategy (How to Not Burn Your Users)

Here’s the rollout plan that survives contact with production:

- Start read-only

- Add pure compute tools

- Add write tools behind:

- role checks

- confirmations

- environment gates

- Run in shadow mode (agent runs, but doesn’t act)

- Launch to a small cohort

- Expand only when telemetry says it’s stable

- Keep a kill switch and a deterministic fallback path

October takeaway

Agents don’t become safe because the model is “smart.”

They become safe because the orchestrator is strict, the tools are well-designed, and the system has telemetry + evals.

Resources

FAQ

No.

Prompting is a way to steer outputs.

Agents are a runtime architecture:

- deterministic orchestration

- strict tool schemas

- permissions

- stop conditions

- observability

- evaluation

If you remove the orchestrator and policy layer, what you have is a demo loop — not a shippable system.

No.

Tool discovery is part of your control plane. Expose tools explicitly via a registry and only include what the current user + context is allowed to access.

The safest system is the one where the model can’t even see forbidden tools.

When you need:

- long-running workflows

- checkpointing

- auditability

- deterministic control over steps

- tight compliance requirements

In those cases, the model should propose plans, but the executor should behave like a workflow engine.

They ship write tools too early.

Read-only agents teach you:

- step limits

- injection risks

- telemetry needs

- evaluation harness design

Write tools multiply risk because failures become real-world damage.

What’s Next

October was about turning a model into a workflow engine — and accepting the consequences:

- side effects

- policy enforcement

- observability

- evaluation

Next month I’m switching from “agents that act” to models that create:

DALL·E: How Text Became Images (and Why It Changed Everything)”

Because once you understand tool use, you see the pattern:

The model isn’t replacing deterministic systems.

It’s becoming the universal interface and composer for them — whether the output is a tool call… or an image.

DALL·E: How Text Became Images (and Why It Changed Everything)

DALL·E wasn’t “just a cool generator.” It turned language into a control surface for visual distributions — and forced product teams to treat image creation like a probabilistic runtime with safety, latency, and cost constraints.

RAG Done Right: Knowledge, Grounding, and Evaluation That Isn’t Vibes

RAG isn’t “add a vector DB.” It’s a reliability architecture: define truth boundaries, build a testable retrieval pipeline, and evaluate groundedness like you mean it.