Pooling, Hierarchies, and What CNNs Are Really Learning

Convolution made CNNs "possible". Pooling and depth made them "useful" - invariance, hierarchies, and feature maps that start to look like learned vision primitives.

Axel Domingues

Last month I finally stopped treating CNNs as “a weird math trick” and started seeing them as an engineering idea:

encode the structure of images into the model so learning becomes easier.

But July still left a big question hanging:

If convolution is “the same detector everywhere”… what are the detectors actually detecting?

And why do CNNs seem to generalize better than older pipelines that used hand-crafted features?

August was about looking inside the box.

Not with hype. With debugging.

What you’ll learn

Why pooling exists, how depth creates hierarchies, and how feature maps become a real debugging tool.

The tradeoffs you’ll keep seeing

Invariance vs precision, compression vs detail, interpretability vs abstraction.

The practical loop

Train → check shapes → visualize feature maps → compare variants → learn the behavior.

The Problem I Wanted to Solve This Month

I wanted to understand three things, concretely:

- Why pooling exists (and what it buys you)

- Why deeper CNNs don’t just “stack edges”

- What feature maps represent in a way I can reason about and debug

Because I’ve learned the hard way: if you can’t inspect a model, you can’t trust it.

- Pooling: downsampling that summarizes a neighborhood (often max/avg), reducing spatial detail.

- Invariance: small input changes (like tiny shifts) don’t drastically change the representation.

- Feature map: the grid output of a filter showing where it “fires”.

- Stride: step size when sliding a filter (also downsamples if > 1).

- Receptive field: how much of the original image a unit depends on.

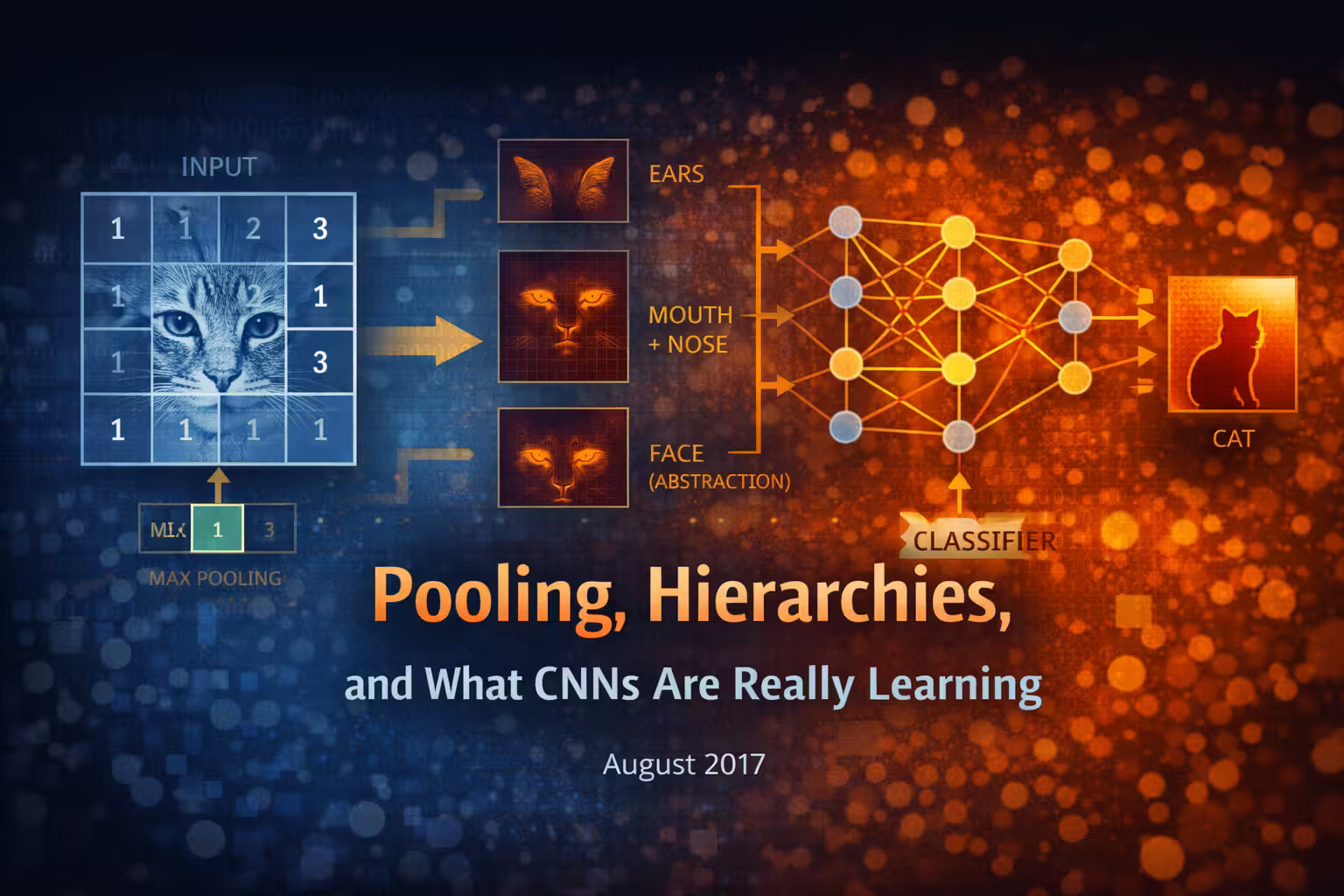

Pooling: The First Time I Felt “Invariance” in My Hands

Pooling sounded like a detail.

It’s not.

The simplest mental model that worked for me:

Pooling throws away exact position information to keep “what” over “where”.

If convolution says:

- “detect an edge anywhere”

Pooling says:

- “I don’t care exactly where in this neighborhood it was — just that it was there”

This is not free. It’s a trade.

When pooling helps

- small translation invariance (tiny shifts matter less)

- smaller representations (speed + lower memory)

- less sensitivity to local noise

When pooling hurts

- tasks needing precise location (segmentation, keypoints)

- when small details are the signal

- when you downsample too aggressively too early

- classification wants invariance → pooling helps

- localization wants precision → pooling can hurt

Max Pooling vs “Just Use Stride” (My First Architecture Argument)

I kept asking myself: why not just increase stride on convolution and skip pooling?

The answer I arrived at was practical:

- stride downsamples while mixing information through learned weights

- pooling downsamples without learning anything new

Pooling acts like a stable, non-learned compression step.

That stability matters when training is already fragile.

So my mental model became:

Convolution extracts, pooling summarizes.

Not a perfect description, but it keeps me honest.

- Stride downsamples while applying learned weights (it changes what gets kept).

- Pooling downsamples without learning (it keeps the compression behavior stable).

That “stability” can make training easier to reason about.

If you want downsampling that also learns which signals matter, stride is attractive.

If you want a predictable summary step to reduce spatial sensitivity, pooling is attractive.

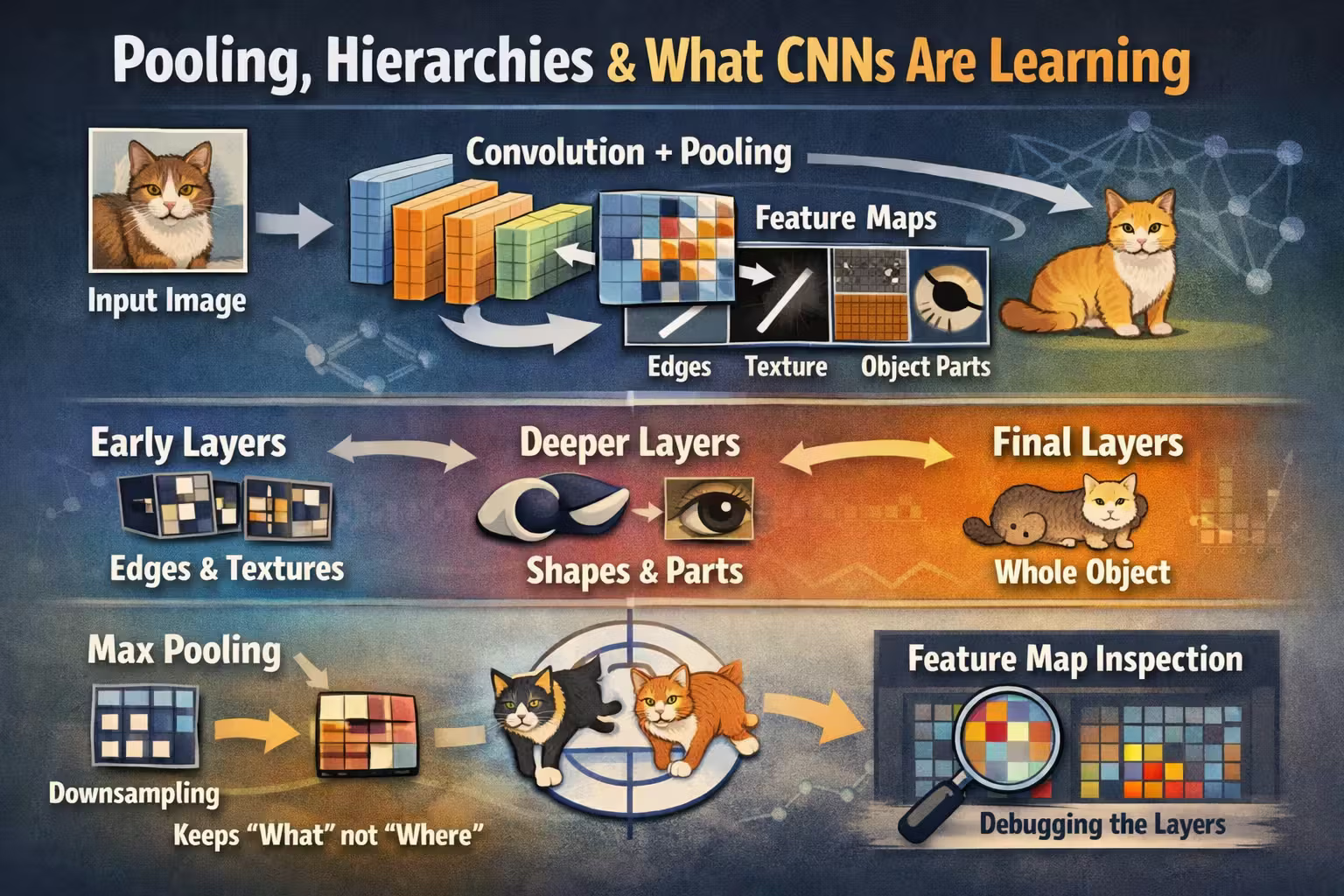

The Hierarchy Idea: Depth Is Not Just “More Layers”

Before CNNs, “deep” sounded like:

- “more parameters”

- “more computation”

- “harder optimization”

CNNs made me see depth differently:

depth builds a hierarchy of representations.

I started grouping what CNNs learn into “levels”:

- early layers: edges, simple textures, contrast patterns

- middle layers: corners, curves, small motifs

- deeper layers: parts of objects, repeated structures

- final layers: category-level cues

That’s the theory.

This month I wanted evidence.

So I forced myself to inspect feature maps.

Feature Maps: The Most Useful Debug Tool I’ve Found So Far

Feature maps are the output of filters.

If a filter is a detector, the feature map is the detector’s “activation heat”.

- Consistency: does the same kind of pattern light up across different images?

- Localization: are activations concentrated on meaningful regions or random noise?

- Progression: do deeper maps look “less pixel-like” and more pattern-like?

- Dead maps: are some maps almost always blank? (maybe unused / bad init / too much downsampling)

- maps that look “busy” everywhere (often noise)

- maps that never change across inputs (bug or collapsed behavior)

- maps that are all zeros (dead units or shape issue)

When I started visualizing them, I had a strong reaction:

CNNs aren’t learning “objects”.

They’re learning a vocabulary of useful visual signals.

A few observations that hit me:

- some maps respond strongly to edges in a certain orientation

- some maps light up on repeating textures (brick, grass-like noise)

- deeper maps become harder to interpret, but still show consistent patterns

- learning curves (for diagnosing bias/variance)

- cost history plots (for optimization sanity)

The “Invariance” Ladder (My New Mental Model)

Pooling created invariance locally.

But stacking conv + pooling repeated creates a ladder:

- early layers are sensitive to small details

- deeper layers become stable to small variations

This is where the whole “representation learning” idea became real to me.

In 2016, PCA was “compress the data while keeping variance”.

In CNNs, the compression is learned and selective:

- not preserving variance

- preserving useful signals for the task

That’s a different objective.

And a different mindset.

Where Dropout Fits (And Why I’m Saving It)

I got asked about dropout recently, and it’s been nagging me.

Dropout is not a CNN-only thing, but it becomes practical right around here because:

- CNNs have a lot of capacity (especially later layers)

- once you stack conv blocks, the classifier head can still overfit hard

- you’ve seen feature maps (the model is learning)

- you’ve seen hierarchies (the model can be powerful)

- now you face the reality: powerful models overfit

I’d keep it focused:

- what dropout does conceptually (“randomly remove units during training”)

- why it behaves like an ensemble-ish regularizer in practice

- how it interacts with CNNs (often more in fully-connected layers; sometimes in conv blocks depending on architecture)

I’m not going deep into “modern best practices” here—just building the intuition that regularization didn’t disappear just because the architecture got smarter.

What I Implemented This Month (My Practical CNN Inspection Loop)

I didn’t want “I read about CNNs” notes.

So I built a small workflow that I can reuse:

Train a tiny CNN on a small image dataset

Not trying to win benchmarks — just enough to learn patterns.

Print and sanity-check tensor shapes at every layer

If I can’t compute the output dimensions by hand, I don’t trust my code.

Visualize feature maps for a handful of inputs

Same few images every time, so changes are comparable.

Compare training with and without pooling

I wanted to feel the difference:

- speed

- stability

- generalization behavior

Add dropout to the classifier head and observe overfitting signals

Not tuning to perfection — just proving the effect exists and is understandable.

Feature map inspection helped me catch that earlier than metrics did.It was thinking a model was learning when it was actually learning noise.

Why This Mattered to Me (Given My 2016 ML Foundation)

In 2016, I learned:

- models overfit

- regularization helps

- diagnostics reveal the real problem

- features matter

August rewired that:

- features are now learned

- invariance is now designed

- diagnostics now include looking inside the layers

The system-thinking mindset stayed the same.

The objects changed.

What Changed in My Thinking (August Takeaway)

Representation learning replaced manual feature design.

Not because feature engineering is “dead” — but because the model architecture became the feature engineering.

Pooling and hierarchies are the bridge: they explain how CNNs go from pixels to meaning without me hand-crafting anything.

What’s Next

CNNs taught me something important:

good architecture is a form of domain knowledge.

But images are still “static”. The input doesn’t have order.

Next month I’m moving to the kind of data that breaks the assumptions I relied on in 2016:

- text

- time series

- sequences

September is where “time” enters the network: Recurrent Neural Networks, unrolling, and shared weights across steps.

FAQ

No. Pooling is useful when you want invariance and lower compute, but it can hurt when you need precise spatial information. I’m treating it as a deliberate tradeoff, not a default.

They’re showing where a filter “fires” on an input. For early layers, that often maps to interpretable patterns like edges. For deeper layers, it becomes less obvious — but still useful for debugging whether the network is learning coherent structure.

Not necessarily. Pooling too often can remove detail too early. A common intuition is: pool when you want to trade spatial precision for invariance and compute savings — but keep enough resolution early so the network can still “see” small patterns.

Why Sequences Break Everything - Enter Recurrent Neural Networks

Images were hard, but at least they were static. Sequences add “time”, shared weights, and state — and suddenly the assumptions I relied on in 2016 stop holding.

Convolutions - Why CNNs See the World Differently

After months wrestling with training stability, I finally hit the next wall - fully-connected nets don’t “get” images. Convolutions felt like the first time architecture itself encoded domain knowledge.