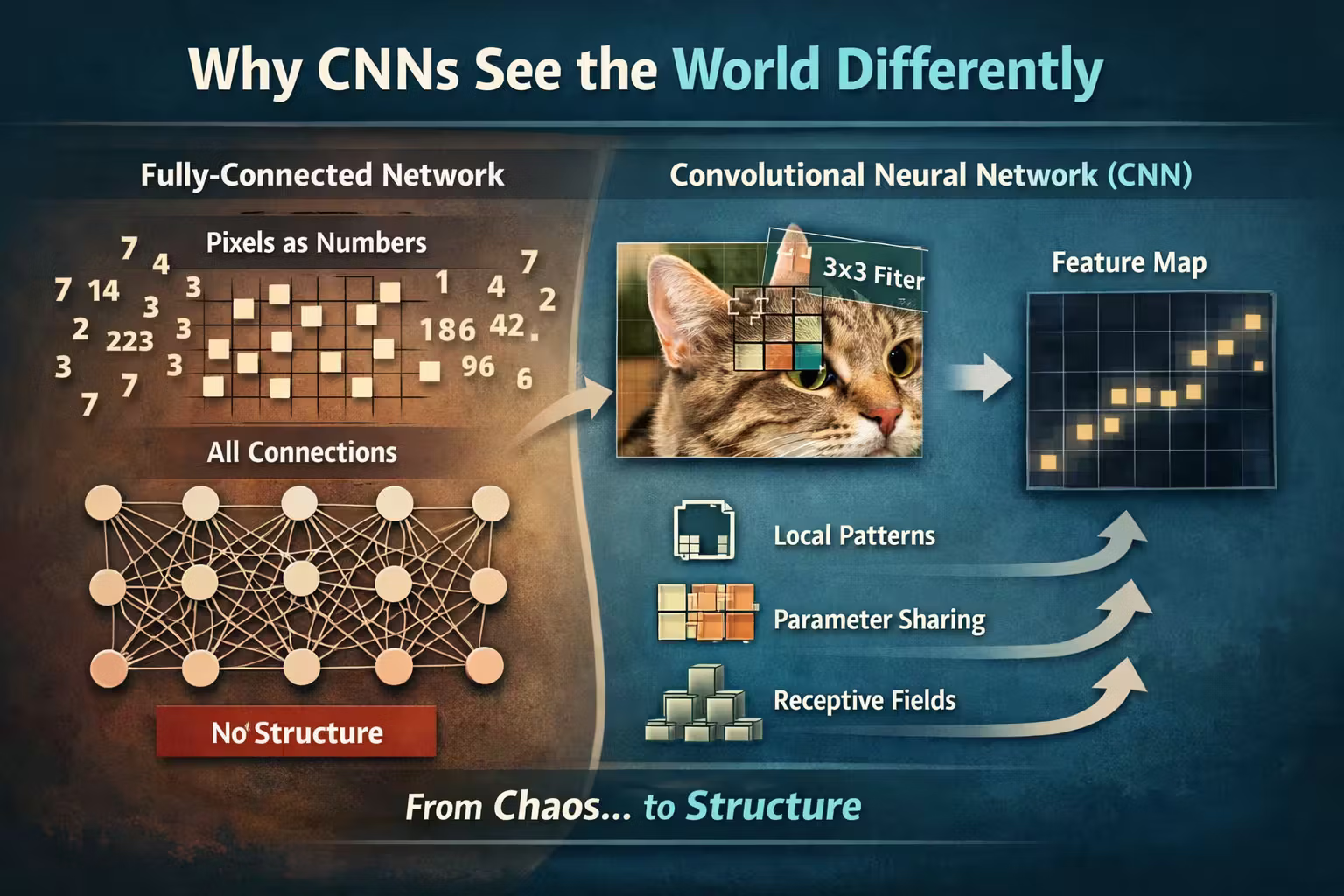

Convolutions - Why CNNs See the World Differently

After months wrestling with training stability, I finally hit the next wall - fully-connected nets don’t “get” images. Convolutions felt like the first time architecture itself encoded domain knowledge.

Axel Domingues

In June, I was finally starting to feel less helpless about optimization.

Momentum gave training inertia. Learning rates stopped being a magic number and became a knob I could reason about.

And then I tried to apply the same mental model to images… and it fell apart.

A fully-connected network looking at pixels is like a model staring at a spreadsheet where the columns have been randomly permuted.

It can still learn something, but it’s fighting the structure of the data.

July was the month I learned why CNNs weren’t “just another neural network”.

They were a different way of seeing.

What this post teaches

Why fully-connected nets “fight” image structure, and how convolutions bake that structure into the model.

The 3 ideas to remember

Locality, parameter sharing, and receptive fields (hierarchy through depth).

The practical skill

How to think about shapes: filter size, stride/padding, output dimensions, parameter count.

The Image Problem I Couldn’t Ignore

A picture is not a bag of numbers.

Pixels have:

- local relationships (edges, corners)

- spatial structure (objects occupy regions)

- patterns that repeat (textures, shapes)

- meaning that survives small shifts (a cat is still a cat if it moves slightly)

A fully-connected network treats every pixel-to-hidden-unit connection as independent and equally likely to matter.

Which creates two immediate issues:

- Too many parameters

- No built-in understanding of locality

In 2016, feature engineering was my way to inject structure. In 2017, CNNs made me realize:

the model can carry the structure.

- Kernel / filter: a small learned pattern detector (e.g., edge-ish detector early on).

- Feature map: the output grid that shows where a filter “fired” across the image.

- Stride: how far the filter moves each step (bigger stride → smaller output map).

- Padding: adding a border so filters can cover edges and output doesn’t shrink too fast.

- Inductive bias: an assumption the architecture bakes in (here: locality matters).

Convolution (My First Non-Magical Definition)

I avoided CNNs for a while because “convolution” sounded like pure signal processing.

But the simplest way I got it into my head was:

A convolution layer applies the same small pattern detector across the entire image.

That’s it.

Pick a small detector

Think “3×3-ish pattern detector” (not because it’s magical, but because images are local).

Slide it across the image

Same detector, everywhere.

That’s the key: you reuse the same weights across positions.

Produce a feature map

Each position outputs one value (how strongly the detector matches there).

Collect those values into a grid: that grid is the feature map.

Instead of one weight per pixel connection, you have a small filter (kernel) that slides across the input and produces an output map.

In practice, it’s like saying:

- “I want to detect an edge”

- “but I don’t care where that edge appears”

- “so I’ll use the same detector everywhere”

That idea has a name:

parameter sharing.

- “a new set of weights for every pixel location” (explodes fast)

- and “one detector reused everywhere” (stays manageable)

And it’s probably the reason CNNs are even possible.

The Three CNN Ideas That Changed My Thinking

Local connectivity

Each unit looks at a small nearby patch, not the whole image.

Parameter sharing

One detector reused everywhere → fewer parameters, more data efficiency.

Receptive fields

Stacking layers grows what a unit can “see” → hierarchy from edges to parts.

1) Local connectivity: “only look nearby”

In a fully-connected net, every hidden unit can depend on every pixel.

In a CNN, a unit depends on a small patch.

That matches how images work:

- edges are local

- corners are local

- textures are local

And it’s exactly the kind of bias that makes learning easier.That assumption is an inductive bias.

2) Parameter sharing: “one detector everywhere”

Instead of learning separate edge detectors for every region, CNNs learn one edge detector and reuse it.

That reduces parameters drastically.

I started seeing this as an engineering tradeoff:

- fewer parameters → less capacity to memorize noise

- fewer parameters → faster training

- fewer parameters → easier optimization

It’s not just “cute architecture”. It’s what makes the problem tractable.

3) Receptive fields: “depth grows your view”

This one took me a while.

Each convolution layer sees a small patch.

But stacking layers increases what a unit can “see”:

- early layers: edges and simple textures

- deeper layers: bigger patterns composed of edges

- deepest layers: object parts and shapes

The key idea is receptive field expansion through depth.

Depth isn’t just “more compute”.

It’s a way to build hierarchical understanding.

From Feature Engineering to Feature Learning (The Real Shift)

In classical ML, I learned to obsess over features.

If the model wasn’t performing, the usual answer was:

- create better input features

- extract domain knowledge manually

CNNs flip that:

- architecture encodes the domain constraints

- training discovers the features

It’s not “no feature engineering”.

It’s feature engineering moved into:

- locality

- translation awareness

- parameter sharing

So this month’s “aha” wasn’t that CNNs are powerful.

It was that CNNs feel like a design decision, not just a training outcome.

In 2017, I started engineering the model to produce its own features.

What I Implemented (My Minimal CNN Sanity Build)

I didn’t try to build a full AlexNet this month. That would have been self-sabotage.

Instead, I forced myself to implement a minimal pipeline that would prove the concept.

My checklist:

- a tiny input (think small grayscale images)

- one convolution layer with a few filters

- a nonlinearity

- a simple classifier head

The goal wasn’t SOTA performance.

The goal was shape sanity and intuition.

What I validated first

- weight shapes: filter dimensions vs input depth

- output shape: how stride/padding affect width/height

- parameter count: CNN vs fully-connected on the same input

- Filter shape: (kernel_height, kernel_width, input_channels, num_filters)

- Output depth: equals num_filters

- Output width/height: depends on input size + padding + stride

Quick mental check:

- padding ↑ → output shrinks less

- stride ↑ → output shrinks more

- more filters → output gets deeper (more feature maps)

- off-by-one output size (stride/padding mismatch)

- swapping width/height at some step

- forgetting the input depth/channel dimension

- off-by-one in output size

- mixing width/height conventions

- forgetting the input depth dimension

This felt weirdly familiar.

In Octave ML exercises, I debugged matrix shapes constantly.

CNNs are basically “shape debugging with more dimensions”.

So my 2016 foundation helped more than expected.

Why This Mattered to Me (With My 2016 Background)

My 2016 instinct was:

if the model is weak, add features

if it overfits, add regularization

if it doesn’t learn, fix optimization

CNNs introduced a new lever:

if the model is blind, change the architecture.

This was the first time I really felt that architecture is a form of prior knowledge.

Not a minor detail.

A choice that can be stronger than:

- more data

- bigger models

- clever optimizers

What Changed in My Thinking (July Takeaway)

I used to think learning was mostly:

- data + optimization + regularization

Now I’m starting to see:

Good inductive bias can outperform brute-force flexibility.

CNNs don’t win because they can represent anything. They win because they represent the right kinds of things for images.

That’s different.

And honestly, it’s kind of relieving.

Because it means deep learning isn’t just “scale and hope for a different outcome”.

It’s design.

What’s Next

Convolutions explained why CNNs work structurally.

But I still didn’t fully understand what they learn internally — and why they generalize so well compared to the older “hand-crafted features + classifier” pipeline.

Next month, I’m going deeper into the CNN stack:

- pooling and why it creates invariance

- feature maps and “what the filters are looking for”

- and how hierarchies emerge layer by layer

August is about understanding CNNs as representation learners — not just convolution operators.

FAQ

Edge detection is a good mental starter, but convolution is broader: it’s “apply the same pattern detector everywhere.” Early layers often learn edges, but deeper layers learn compositions of those patterns.

You can, but you waste parameters and ignore locality. CNNs build the right assumptions into the model, which makes learning more data-efficient and easier to optimize.

Shapes. Output dimensions, filter depth, padding/stride interactions. The math is fine — the bookkeeping is where you bleed.

- Stride changes how far the filter moves each step. Bigger stride → smaller feature map.

- Padding adds a border so filters can cover edges and output doesn’t shrink too aggressively.

If your output shape surprises you, stride/padding are usually the first suspects.

Pooling, Hierarchies, and What CNNs Are Really Learning

Convolution made CNNs "possible". Pooling and depth made them "useful" - invariance, hierarchies, and feature maps that start to look like learned vision primitives.

Optimization Got Real - Momentum, Learning Rates, and Why Plain Gradient Descent Wasn’t Enough

In 2016, gradient descent felt like “the algorithm.” In deep learning, it’s just the beginning. This month I learned why momentum and careful learning rates are what make training "actually move".