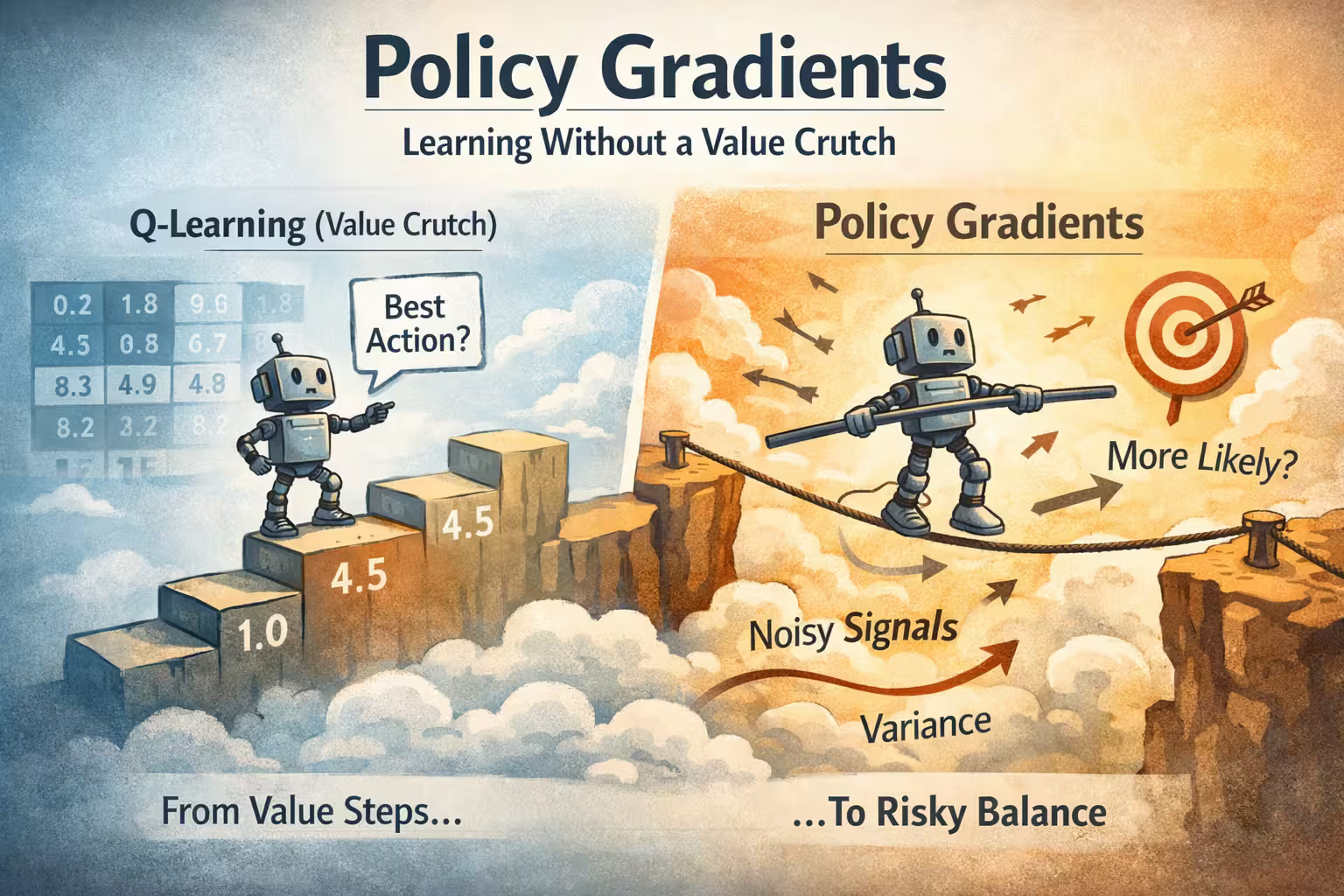

Policy Gradients - Learning Without a Value Crutch

DQN taught me how fragile value learning can be. This month I tried something different - learn the policy directly. No Q-table. No value “crutch.” Just behavior, gradients, and a whole new set of failure modes.

Axel Domingues

May was my first real month running deep RL systems end-to-end.

And DQN did what I expected:

- it worked… sometimes

- it broke… often

- and when it broke, it broke like a system, not like a bug

But the deeper lesson was more specific:

Value learning is powerful, but it’s a crutch.

A Q-function can hide confusion behind numbers. A value estimate can drift for a long time before the reward curve tells you the truth.

So in June I wanted to learn a different kind of honesty:

What happens if I stop trying to estimate value first… and just learn behavior?

That’s policy gradients.

This month felt like stepping off a staircase and learning to walk on a rope.

The shift

From “pick the best action” → to “become more likely to pick it.”

The new failure mode

Noisy gradients.

Runs diverge because the signal-to-noise ratio is brutal.

The June dashboard

Behavior + entropy + gradient norms replace Q-values as my truth sources.

The takeaway

Policy gradients are clean in theory, but variance control is the real job.

The Shift: From “What’s the Best Action?” to “Become More Likely to Do It”

With DQN, my mental model was:

- “the network outputs action values”

- “pick the action with the highest value”

- “train so predicted values match improved targets”

With policy gradients, the model changes:

- the network outputs a distribution over actions

- the agent samples from it (especially early)

- learning nudges the distribution so actions that lead to good outcomes become more probable

DQN (value-first)

Predict action values, then act.

Learning depends on value targets staying sane.

Policy gradients (policy-first)

Predict an action distribution.

Learning nudges probability toward rewarded actions.

What gets simpler

No Q-scale drift, no target network (in the naive form), fewer moving parts.

What gets harder

Variance explodes.

One lucky episode can yank the policy the wrong way.

This felt strangely familiar to deep learning:

Instead of predicting labels, the network predicts choices.

And training is about shifting probability mass.

The Surprising Part: It Feels More “End-to-End”… and Less Stable

Policy gradients felt conceptually cleaner than DQN:

- no replay buffer to manage (in the simplest form)

- no target network to stabilize

- no Q-values drifting into absurd scales

But the cost of that cleanliness showed up immediately:

the gradient signal is noisy.

Sometimes wildly noisy.

It reminded me of early deep learning experiments:

You can do everything “right” and still get a run where nothing useful happens.

Not because it’s broken.

Because the signal-to-noise ratio is brutal.

“I understand the algorithm… but the learning curve doesn’t care.”

The First Honest Lesson: Variance Is the Enemy

I didn’t need a formal proof to understand the problem.

I felt it in training:

- two runs with the same settings can diverge early

- small randomness in action selection can change the entire trajectory

- reward signals can be delayed and sparse

- and the policy update can overreact to one lucky episode

So this month became an obsession with variance.

Not “performance tuning.”

Variance control.

That’s what made policy gradients feel like engineering.

What I Watched Instead of Q-Values

In DQN I stared at:

- reward curves

- Q-value scale

- TD error

- loss curves

In policy gradients, those are replaced by a different set of signals.

These became my “June dashboard”:

Behavior

Reward, episode length, and whether behavior is actually improving.

Exploration

Entropy + action distribution drift (am I collapsing too early?).

Update health

Gradient norms + policy step size (are updates exploding or vanishing?).

Stability

KL divergence (if tracked) + advantage stats (if using a baseline).

- average episode reward (always)

- episode length (often a proxy for competence)

- short rollouts to verify behavior matches curves

- entropy over time (early collapse is usually fatal)

- action distribution drift

- gradient norms (explode? vanish?)

- policy loss trend (never trusted alone)

- KL divergence old vs new policy (if tracked)

- advantage mean/variance (if using a baseline)

- baseline/value loss (if present)

The biggest mindset shift:

I stopped thinking “loss down = progress.”

And started thinking:

“Are my updates small, consistent, and directionally sensible?”

If entropy collapses too early, the agent stops exploring and policy gradients become self-reinforcing failure.

The “No Value Crutch” Part… Isn’t Totally True

At first I wanted a pure form:

- no value function

- no critic

- just policy

But I learned quickly why people introduce baselines:

A baseline reduces variance without changing what “good” means.

So even in “policy gradient month,” I ended up appreciating:

- the idea of subtracting a baseline from returns

- the idea that learning can be unbiased but still untrainable due to variance

- the fact that “correct” and “practical” are not the same thing

This is a pattern I keep seeing in RL:

The pure idea is elegant.

The working idea has guardrails.

Where It Worked Best (And Where It Lied)

Policy gradients felt best in environments where:

- reward signal is reasonably frequent

- exploration isn’t catastrophically expensive

- the policy can improve incrementally

They felt worst in environments where:

- reward is sparse

- one early mistake can poison learning

- success requires long-term credit assignment

In other words:

Policy gradients are not a magic escape hatch from RL instability.

They are a different instability profile.

Common Failure Modes I Expect Now (Policy Gradient Edition)

By the end of June, I had my own list of “things I now assume will break”:

Likely cause: the policy became deterministic too soon

First check: entropy curve + action distribution; slow the collapse before you celebrate reward

Likely cause: updates are too small or the task is too hard for the current setup

First check: gradient norms; validate on CartPole to confirm the pipeline can learn anything

Likely cause: high variance returns + overreaction to lucky episodes

First check: multiple seeds; examine advantage/return variance; consider baseline/normalization

Likely cause: step size too large; policy changed too fast

First check: KL divergence (if tracked) or proxy via update magnitude; reduce step size

Likely cause: credit assignment pain

First check: inspect trajectory examples; shorten horizon / simplify env to verify learning signal

- They don’t always “explode.”

- Sometimes they just… do nothing.

- And you can’t tell if you’re close to learning or completely stuck.

The Debugging Habits I Built This Month

June forced me to develop a new discipline:

Treat the policy like a living object you can measure.

Here’s the checklist I kept coming back to:

Watch entropy first

If entropy collapses early, I’m not learning—I’m committing.

Confirm reward scale

If rewards are huge or tiny, policy updates can become meaningless or chaotic.

Inspect advantage stats (if using a baseline)

If advantages are all near zero or wildly spiky, the training signal is unstable.

Evaluate separately

I always separate training (stochastic) and evaluation (more deterministic) to know what I actually trained.

Reduce the environment until it’s learnable

If it fails in a hard task, I go back to something like CartPole to validate the pipeline.

The recurring deep learning lesson returns again:

Start small. Confirm learning. Scale complexity.

Field Notes (What Surprised Me)

1) Policy gradients feel psychologically “cleaner”

I like the story: reward should reinforce behavior.

There’s no intermediate “value world” that can drift silently.

2) But the noise is real

I underestimated how much randomness dominates early learning.

This month taught me why baseline/advantage tricks exist.

3) Exploration is now baked into the policy itself

With DQN, exploration felt like a separate switch (epsilon).

Here, exploration is part of the policy shape. Entropy isn’t a side metric — it’s part of the agent’s survival.

4) This is where RL started to feel like “probability engineering”

I’m no longer tuning a predictor.

I’m tuning a probability distribution that changes the data it receives.

That loop is the whole game.

June takeaway

Policy gradients remove the value “crutch,” but they replace it with a harder truth:

variance is the enemy, and instrumentation is the only way to stay honest.

What’s Next

June convinced me of something important:

Policy gradients are the right direction, but naive policy gradients are too noisy.

I can feel the need for structure:

- better credit assignment

- less variance

- more stable updates

So next month I’m moving into the thing everyone points to as the “workhorse” of deep RL:

Actor-Critic.

The promise is simple:

- keep the directness of policy learning

- add a critic to reduce variance

- make learning faster and more stable

But based on how this year is going…

I’m sure the critic will introduce its own new ways to break.

And that’s exactly what I want to understand.

FAQ

Kind of — and that’s the point.

I started this month wanting “policy only.” But I learned quickly that variance can make a correct gradient unusable.

A baseline doesn’t change what counts as good behavior — it just makes the learning signal less noisy. That tradeoff feels like real engineering.

In DQN I worried about Q-values drifting and targets becoming unstable.

Here I worry about:

- entropy collapsing

- high variance updates

- and the policy changing too fast or not at all

It’s less about “value sanity” and more about “policy stability.”

Because I’m trying to understand the building blocks.

If I jump to a stabilized method too early, it works like a black box. This month was about feeling the raw instability so I know what the stabilizers are actually fixing.

Actor-Critic - The First Time RL Feels Trainable

Policy gradients were honest but noisy. This month I added a critic—and for the first time in RL, training started to feel like something I could actually steer.

Deep Q-Learning - My First Real Baselines Month

This is the month I stopped reading about deep RL and started running it. DQN is simple enough to explain, hard enough to break, and perfect for learning Baselines like an engineer.