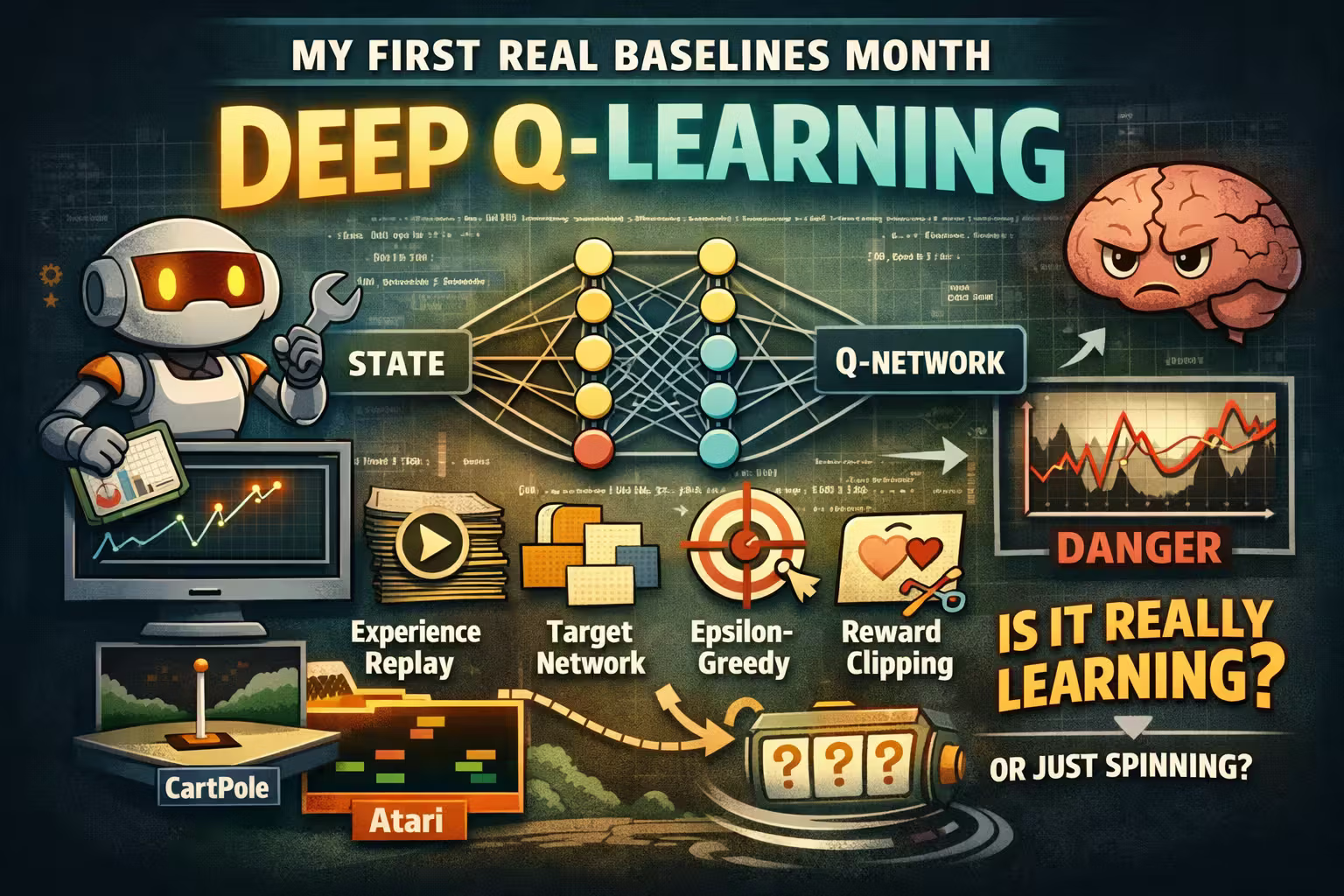

Deep Q-Learning - My First Real Baselines Month

This is the month I stopped reading about deep RL and started running it. DQN is simple enough to explain, hard enough to break, and perfect for learning Baselines like an engineer.

Axel Domingues

April was the warning label.

The moment I replaced a Q-table with a function approximator, RL stopped behaving like a tidy algorithm and started behaving like a fragile system.

So in May I did the obvious thing:

I leaned into it.

This is the month I finally used OpenAI Baselines in anger — not as a library to admire, but as a machine to operate, instrument, and debug.

And I picked the most classic deep RL entry point possible:

Deep Q-Learning (DQN).

Not because it’s the easiest.

Because it’s the first one where I can look at a training run and ask:

“Is this actually learning… or is it just spinning?”

- run a deep RL system end-to-end

- interpret its metrics

- and debug it when it behaves strangely

The goal this month

Run DQN end-to-end and learn what “learning” looks like in practice.

The mindset shift

Baselines isn’t a library to admire.

It’s a machine to operate + instrument + debug.

What I’m measuring

Reward isn’t enough.

I watch behavior + Q-health + exploration + data pipeline.

What counts as progress

Beats random reliably (multiple seeds), and behavior matches the curve.

Why DQN Is the Perfect First Deep RL System

DQN is conceptually satisfying:

- it’s still value-based, like tabular Q-learning

- it still tries to answer: “how good is this action in this state?”

- it uses a neural network as the Q-function approximator

- and it learns from experience

So in my head, it’s a clean continuation of March + April:

- March: Q-values in a table

- April: Q-values as a model

- May: Q-values as a neural network trained from experience

But in practice?

DQN is where RL starts to feel like engineering a moving machine.

Because DQN isn’t “one idea.”

It’s a bundle of ideas whose job is to prevent the system from blowing up.

DQN Felt Like a Bundle of Safety Systems (Not Just an Algorithm)

When people explain DQN casually, it sounds like:

“Just use a neural net to approximate Q-values.”

But Baselines DQN taught me the real story:

DQN is a stack of stabilizers.

Stabilize the data

Experience replay breaks correlation and makes learning less “chasey”.

Stabilize the target

Target networks slow the moving target so the value function can converge.

Stabilize behavior

Exploration schedules prevent early lock-in and keep data diverse.

Stabilize scale

Reward + input preprocessing prevent huge gradients and nonsense values.

Here are the ones that stood out immediately:

- experience replay (break correlation)

- target network (stop chasing a moving target too aggressively)

- epsilon-greedy exploration (avoid premature lock-in)

- reward clipping / normalization (keep learning signals sane)

- frame preprocessing (reduce the input chaos)

- delayed updates / warm-up steps (don’t learn from garbage early)

This is where my 2017 mindset came back full force:

Training isn’t “running an algorithm.”

Training is building a stable feedback system.

And start asking: “What are the stabilizers, and what happens if one fails?”

The Environments I Used to Stay Sane

I didn’t start with Atari.

Atari is where you go to feel humbled.

I started with environments that let me isolate failure modes.

My progression looked like this:

- CartPole (fast feedback, simple dynamics)

- MountainCar (reward is sparse enough to expose exploration issues)

- Acrobot (harder control, still manageable)

- then finally: a first Atari run (mostly to feel the scale of the problem)

What surprised me is how quickly “simple” environments still break when the training loop is misconfigured.

Deep RL can fail quietly even when the task is easy.

What I Watched Like a Hawk

In supervised learning, I watch:

- training loss

- validation loss

- accuracy

In DQN, that mindset is necessary but not sufficient.

The first week of May I basically stared at reward curves and got fooled repeatedly.

So I built a more RL-specific mental dashboard.

Here’s what I learned to pay attention to:

Behavior signals

Is the agent actually acting better over time?

Value function health

Are Q-values and TD errors staying sane?

Exploration signals

Is the agent still sampling enough to learn the right thing?

Data pipeline signals

Is the replay buffer feeding useful, varied experience?

- average episode reward (across many seeds)

- episode length (often tracks competence in control tasks)

- Q-value scale (drift upward wildly?)

- TD error magnitude (explode? vanish?)

- loss curve (useful, but never “the truth”)

- epsilon schedule behavior (am I actually exploring?)

- action distribution (am I collapsing into one action?)

- replay buffer fill level

- fraction of random actions vs policy actions early on

The First Deep RL “Failure That Felt Real”

In tabular RL, failure is usually obvious:

- value table doesn’t converge

- policy is wrong

- exploration is insufficient

In DQN, I hit a failure mode that felt different:

Everything looked like it was working.

The run produced numbers. The plots moved.

But the agent’s behavior didn’t actually improve in a way that made sense.

It was the first time I felt:

The system can generate convincing training noise that looks like progress.

That’s the psychological trap of deep RL.

So I started validating in a very blunt way:

- watch short rollouts

- check whether behavior changes match the reward curve

- run evaluation episodes with exploration minimized

- compare to random policy baselines

If the “learned” agent didn’t beat random clearly, I assumed I was hallucinating progress.

What “Debugging” Looked Like This Month

Debugging in DQN felt less like “fixing code” and more like “diagnosing dynamics.”

These were my recurring moves:

Confirm the loop is wired correctly

Before blaming deep RL, I verify:

- the environment actually returns rewards the way I think it does

- episodes reset correctly

- reward is not always zero because of a wrapper mistake

Check exploration first

If the agent isn’t learning, I assume:

- it isn’t exploring enough

- or exploration is decaying too fast

Check Q-value sanity

I inspect whether Q-values:

- stay within a plausible scale

- drift slowly upward forever

- collapse to near-constant outputs

Validate with evaluation mode

I separate:

- training episodes (exploration on)

- evaluation episodes (exploration reduced)

Reduce complexity until it works

If it fails in a hard environment, I go back to:

- CartPole

- and verify the full stack can learn something easy

This felt similar to debugging deep nets in 2017:

start with a known-good baseline and shrink the problem until the system behaves.

Common Failure Modes I Now Expect (DQN Edition)

Here’s the list I wrote by the end of May — the things I now assume will break before I assume “the algorithm doesn’t work”:

Likely cause: epsilon decays too fast

First check: log epsilon over time + action distribution

Likely cause: replay too correlated or learning rate too high

First check: replay size + TD error + loss spikes

Likely cause: value scale instability (target chase, reward scale)

First check: Q min/mean/max over time + reward scale/clipping

Likely cause: evaluation accidentally uses exploration

First check: separate train vs eval settings explicitly

Likely cause: brittle configuration / luck

First check: run 5+ seeds; treat “one good run” as a hint, not a result

A single successful run is not a result. It’s a hint.

Field Notes (What Surprised Me)

1) DQN is less “one method” and more “a stability recipe”

Before Baselines, I thought DQN was an algorithm.

After Baselines, it felt like a system design pattern:

- break correlations

- slow the moving target

- control exploration

- tame reward scale

- don’t learn too early from junk

2) Reward is not a trustworthy metric early

This month reinforced February’s bandit lesson:

Early reward is noisy, and in deep RL it can be misleadingly noisy.

3) The value function can become pathological long before reward shows it

If you don’t watch Q-value scale and TD error stats, you can drive straight into a cliff with a “fine-looking” curve.

4) Baselines is a teacher… if you read its signals

The library exposes enough diagnostics to make the learning process inspectable. But you have to actually look.

May takeaway

DQN isn’t one idea.

It’s a stack of stabilizers — and debugging means finding which stabilizer is failing first.

What’s Next

May was my first month where deep RL felt tangible:

- I could run something real

- watch it learn (or not)

- and debug it like a system

But DQN has a limitation I can’t ignore:

It’s built for discrete actions.

And it leans heavily on value estimation, which can be brittle.

Next month I’m switching gears:

Policy gradients.

Not because they’re easier.

Because I want to learn the other half of deep RL:

- direct optimization of behavior

- stochastic policies

- and the first time “entropy” becomes a real debugging signal

If DQN taught me how value-based deep RL breaks…

June will teach me how policy-based deep RL breaks.

FAQ

Because it’s the cleanest bridge from tabular Q-learning.

The idea is familiar: learn action values. The novelty is the stability stack required to make that idea work with a neural network.

Because for the first time I wasn’t just learning concepts.

I was running a real RL system end-to-end, reading its diagnostics, and learning how to interpret behavior from training signals. Baselines forces you to confront the practical reality of deep RL.

Deep RL success is not one trick.

It’s a fragile stack of stabilizers. If you don’t understand what each stabilizer does, you can’t debug the system when it inevitably misbehaves.

Policy Gradients - Learning Without a Value Crutch

DQN taught me how fragile value learning can be. This month I tried something different - learn the policy directly. No Q-table. No value “crutch.” Just behavior, gradients, and a whole new set of failure modes.

Function Approximation - The Day RL Stopped Being Stable

Tabular RL felt clean because you could see the truth in a table. The moment I replaced the table with a model, RL stopped being a neat algorithm and became a fragile system.