Actor-Critic - The First Time RL Feels Trainable

Policy gradients were honest but noisy. This month I added a critic—and for the first time in RL, training started to feel like something I could actually steer.

Axel Domingues

June was a month of pure policy gradients.

And it taught me a humbling truth:

I can understand an algorithm and still get nothing but noise out of it.

Not because it’s wrong.

Because RL is a feedback loop where the data comes from the model itself.

And the first version of that loop is usually too noisy to drive.

So July was about the first piece of “RL engineering” that made immediate sense:

Add a critic.

Not because I want to go back to value learning as the main thing.

But because I want a training signal that doesn’t feel like shouting across a canyon.

Actor-critic is where RL started to feel… trainable.

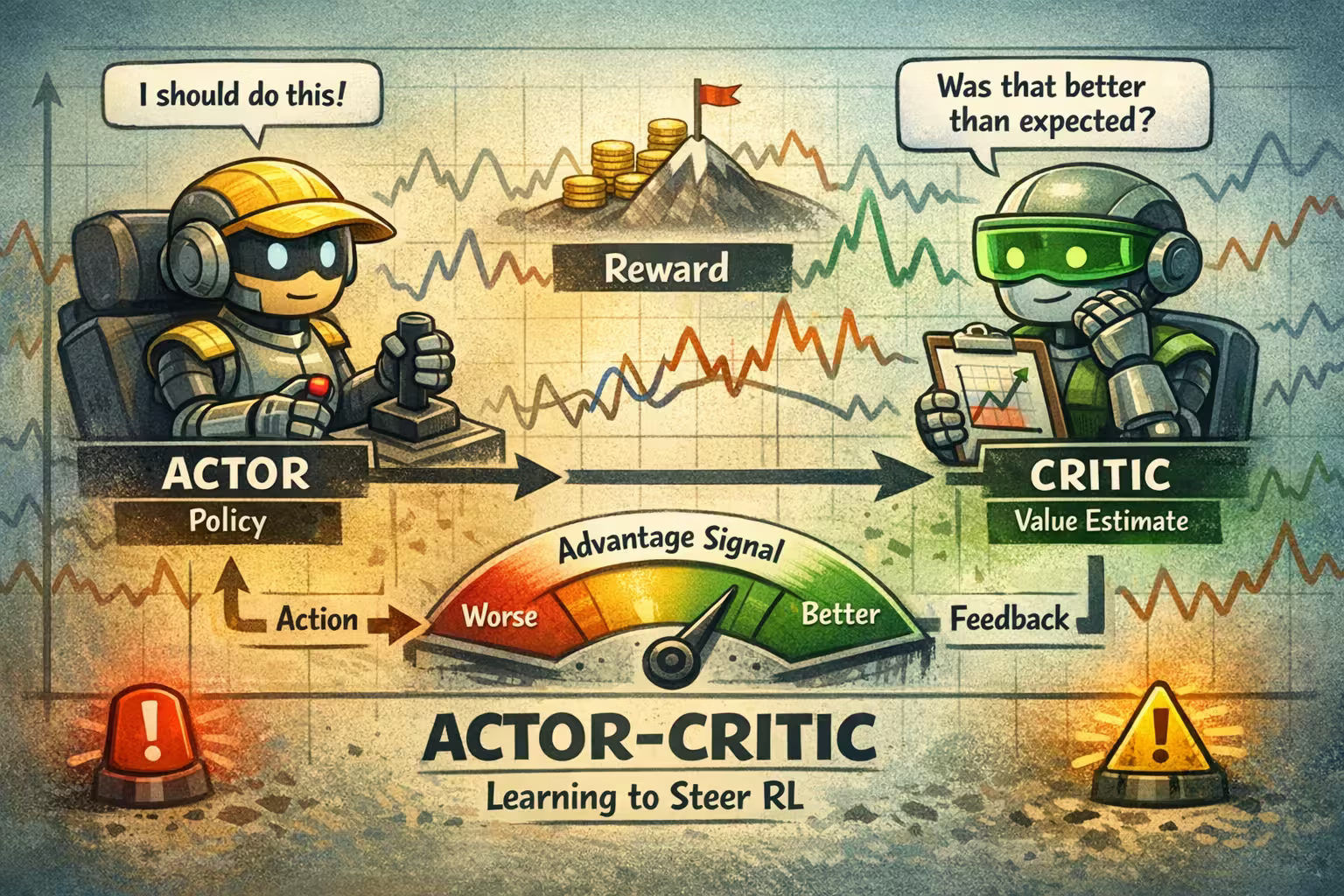

- the actor learns what to do (the policy)

- the critic learns how good things are (a value estimate)

- the critic exists to make the actor’s updates less noisy

It’s more usable.

The core idea

Keep policy learning, add a value baseline so updates stop feeling like noise.

The two parts

Actor = policy.

Critic = value estimate.

The interface

Advantage turns reward into “better than expected” (a usable training signal).

The engineering win

Two models means more failure modes — but also warning lights you can monitor.

The Pitch: “Keep Policy Learning, Borrow Value Stability”

In June, my mental model was:

“Reward reinforces behavior.”

In July, the model gained a second voice in the agent’s head:

- Actor: “I should do action A more often.”

- Critic: “Only if it was actually better than expected.”

That phrase “better than expected” is the key.

Advantage answers: “Was this action better or worse than my baseline expectation?”

- positive advantage → reinforce this action more

- negative advantage → reinforce it less

- near zero → mostly noise (don’t overreact)

The critic exists to make this comparison possible.

The critic doesn’t need to predict everything perfectly.

It just needs to provide a reference point so the actor can tell whether an episode was:

- better than baseline

- worse than baseline

- or basically noise

This is where the word advantage started to feel less like jargon and more like an interface.

The critic turns raw reward into a shaped signal:

“That action helped more than the baseline predicted.”

My July “Aha”: The Critic Is a Noise Filter

I used to think the critic was a second model you train “because papers say so.”

But once I watched training behavior with and without it, it became obvious:

- without a critic, the actor updates on high-variance returns

- with a critic, the actor updates on relative surprise

And relative surprise is a cleaner signal.

It’s not perfect.

But it’s steerable.

In actor-critic, the advantage estimate is the interface.

If the advantage signal is garbage, the actor will learn garbage very confidently.

What Changed in My Debugging Approach

With policy gradients, I obsessed over:

- entropy collapse

- reward scaling

- “is my gradient exploding?”

With actor-critic, I added a new rule:

If the critic is wrong, it will mislead the actor.

So I started treating the critic like a system component that could fail independently.

That meant tracking two kinds of health signals:

Actor health

Entropy + action drift + policy update size.

Critic health

Value scale, value loss sanity, explained variance.

Advantage health

Mean near zero-ish, variance not extreme, signs not all one-way.

The rule

If the critic is wrong, it will confidently mislead the actor.

- entropy trend (still crucial)

- action distribution drift (collapse patterns)

- policy loss magnitude (only as a hint)

- value loss (sane, not necessarily monotonic)

- explained variance (does it predict anything?)

- value scale vs reward scale (order-of-magnitude sanity)

- mean advantage (should hover around zero-ish)

- variance (too high = noise, too low = no signal)

- sign balance (all + or all − usually means something broke)

This month I stopped staring at reward curves alone.

Reward curves are the outcome.

Actor-critic gave me internal instruments.

The First Time I Could Predict What Would Break

This is the best compliment I can give an algorithm:

It failed in ways I could name.

Here’s my July failure mode list—the one I kept returning to.

Likely cause: exploration dies; actor gets stuck

First check: entropy curve + action distribution drift

Likely cause: policy updates too large (step size / advantage scale)

First check: KL between policies (if available) + advantage variance

Likely cause: updates too small or advantages near zero everywhere

First check: advantage variance + critic explained variance

Likely cause: critic underfits → advantage is mostly noise

First check: explained variance ~0 and value loss not improving at all

Likely cause: critic overfits / chases noise

First check: critic loss looks “good” but advantage signs look wrong / unstable

Likely cause: value scale instability → misleading advantages

First check: value min/mean/max vs reward scale

Likely cause: coupled instability (bad critic → bad actor → worse data → worse critic)

First check: advantage normalization, value drift, and sudden KL spikes together

Why This Month Felt Like “Training” Again

There’s a very specific feeling I associate with trainability:

When I tweak one knob and the system reacts in a way that makes sense.

In June, knobs felt like roulette.

In July, knobs started to feel like engineering controls:

- increase entropy bonus → exploration lasts longer

- reduce step size → fewer catastrophic collapses

- improve value learning → policy stabilizes faster

- normalize advantages → updates become consistent

It wasn’t magic.

It was feedback.

What I Ran (Conceptually) to Keep the Jump Gentle

I kept the environments intentionally conservative this month.

Actor-critic is already a complexity jump because you’re training two networks at once.

So I focused on settings where:

- learning signal is frequent

- debugging cycles are fast

- “success” is clearly visible

That meant classic Gym control tasks first (fast feedback), with an eye toward scaling later.

What I Watched During Runs (My July Checklist)

This became my “actor-critic dashboard,” the stuff I’d check before I believed any reward curve:

Outcomes

Episode reward + episode length (cheap competence proxy).

Actor behavior

Entropy trend + action distribution (collapse detection).

Critic sanity

Value scale + explained variance (is it predicting anything?).

Update safety

Advantage stats + KL (if available) + gradient norms when unstable.

- entropy didn’t collapse instantly

- advantage mean is near zero-ish

- advantage variance is not extreme

- explained variance is not near zero forever

- KL didn’t spike (if I have it)

Field Notes (What Surprised Me)

1) The critic doesn’t need to be “right,” it needs to be “useful”

I kept expecting the critic to become accurate.

That’s not the goal.

The goal is to produce an advantage signal that reduces variance and points in the right direction.

2) Actor-critic still fails, but it fails with warning lights

This was huge for morale.

With pure policy gradients, failure can look like silence.

With a critic, I often get clues:

- value loss exploding

- explained variance near zero

- advantages all same sign

It’s not easier, but it’s more diagnosable.

3) RL is still an interface problem—now I just have more interfaces

In January I wrote that “learning is an interface problem.”

Actor-critic made that literal:

- the actor interface is probability

- the critic interface is value

- the bridge interface is advantage

If any of these interfaces is poorly designed, learning becomes chaotic.

July takeaway

The critic isn’t there to be right.

It’s there to make the actor’s update step usable — a training signal I can steer.

What’s Next

July made RL feel trainable for the first time.

But it also revealed a new anxiety:

actor-critic is sensitive to how big each update step is.

Sometimes learning looks good… and then collapses because the policy changed too much too fast.

So next month I’m going to lean into the stability question directly:

- How do I prevent catastrophic updates?

- How do I keep learning “inside a safe region”?

- How do I measure when the policy changed too much?

That’s where methods like TRPO start to make sense.

Not as fancy math.

As safety rails.

August is where I stop asking “does it learn?”

And start asking:

can I trust the learning step?

FAQ

Kind of—and the “extra steps” are the point.

Pure policy gradients use raw returns, which are noisy. Actor-critic replaces raw returns with an advantage estimate shaped by a value baseline.

It’s still reinforcing behavior. It’s just doing it with a signal that has less variance.

Treating the critic as a first-class system component.

If the critic is unstable or meaningless, the actor becomes unstable even if the policy code is fine.

Watching explained variance and advantage stats gave me early warning signals that reward curves alone don’t provide.

Yes, and that surprised me.

Not because the math is the same—but because the workflow became familiar:

- monitor internal signals

- adjust step sizes and regularization-like terms (entropy)

- build confidence in stability before chasing performance

That “training as engineering” mindset finally carried over cleanly.

Why RL Training Is Unstable (A Catalog of Breakage)

After actor-critic finally felt “trainable,” I hit the next wall - RL doesn’t just fail—it fails in loops. This month is my map of the most common ways it breaks.

Policy Gradients - Learning Without a Value Crutch

DQN taught me how fragile value learning can be. This month I tried something different - learn the policy directly. No Q-table. No value “crutch.” Just behavior, gradients, and a whole new set of failure modes.