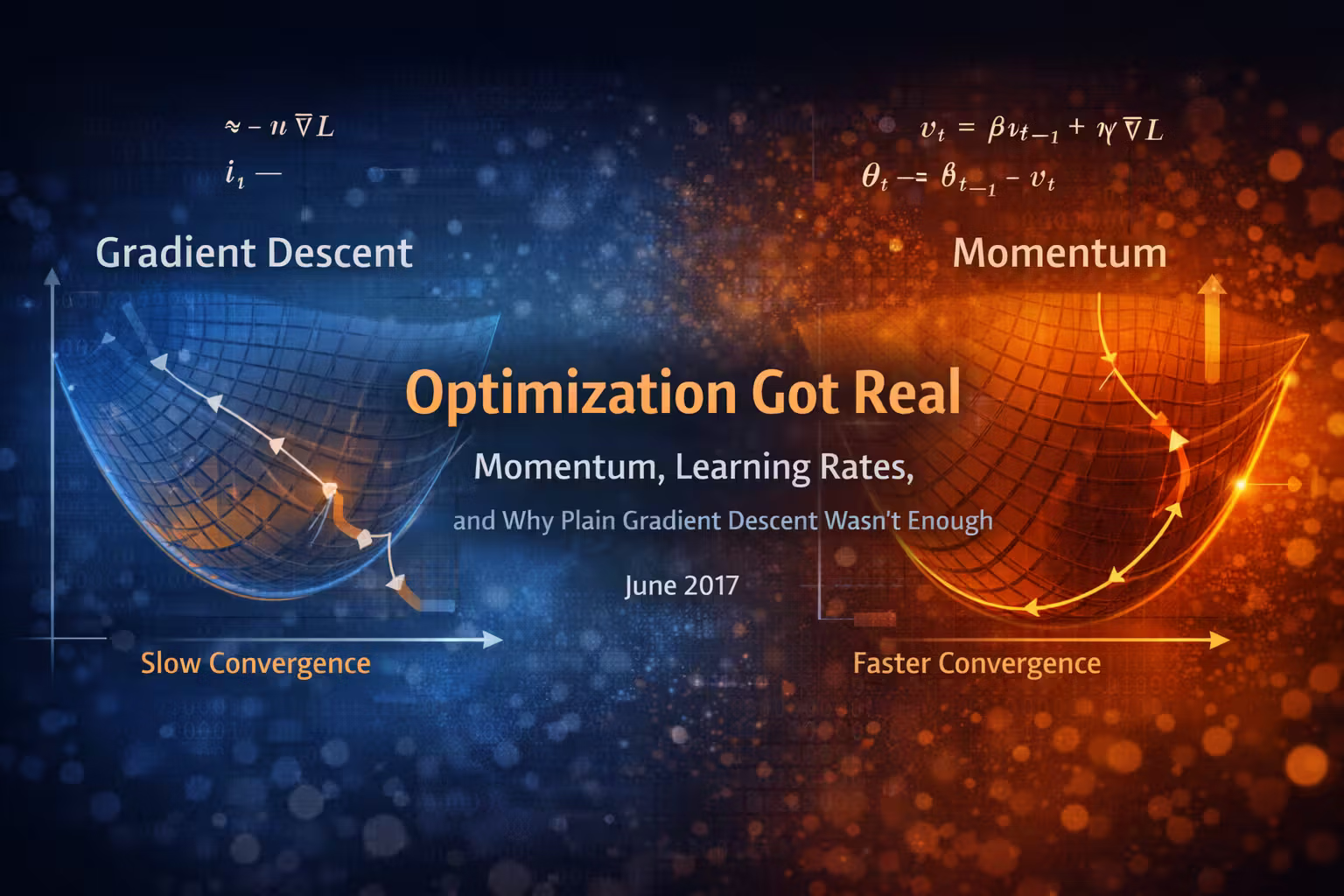

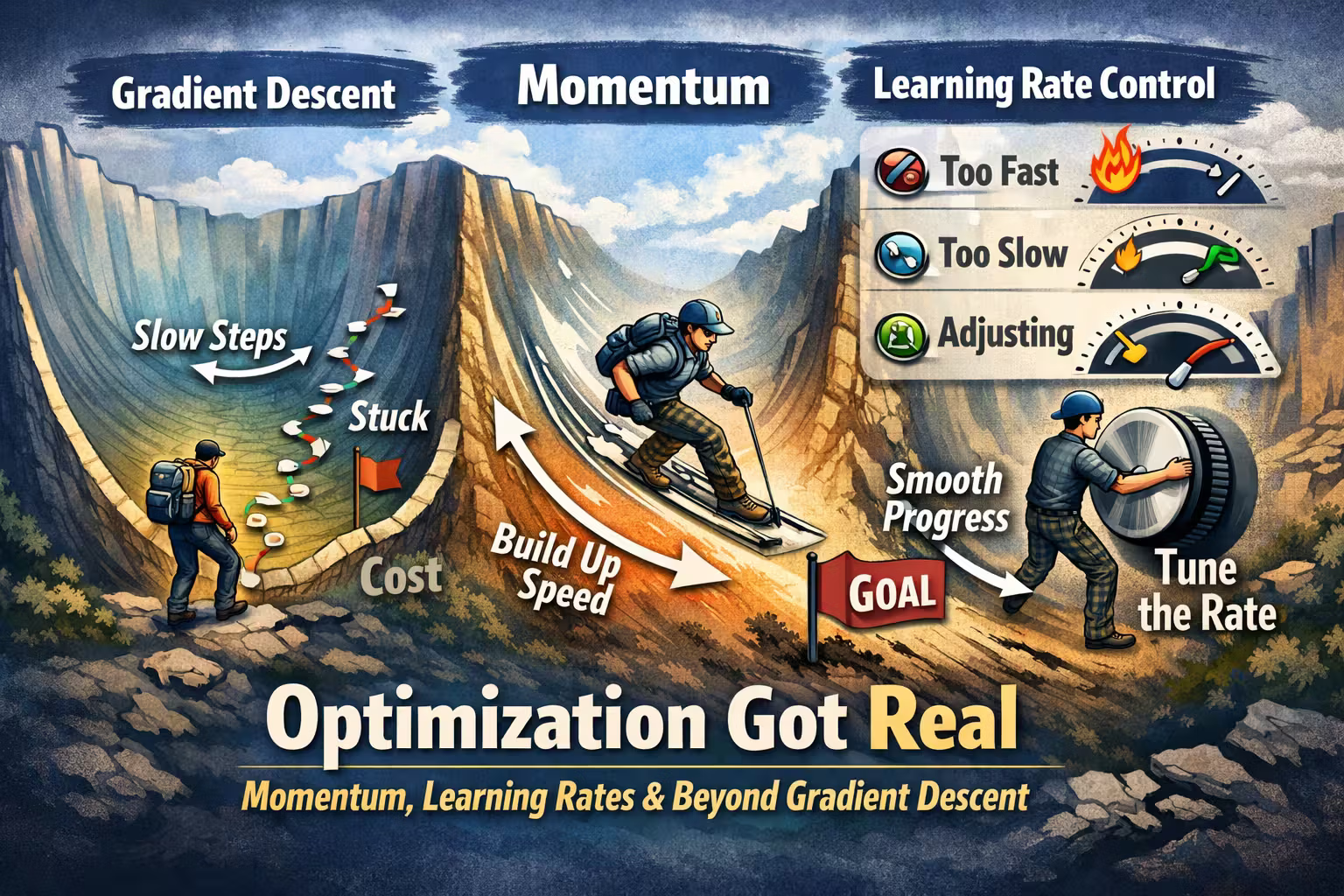

Optimization Got Real - Momentum, Learning Rates, and Why Plain Gradient Descent Wasn’t Enough

In 2016, gradient descent felt like “the algorithm.” In deep learning, it’s just the beginning. This month I learned why momentum and careful learning rates are what make training "actually move".

Axel Domingues

In 2016, gradient descent was the hero of the story.

I built intuition for it in the Andrew Ng course:

- the cost bowl

- the descent path

- feature scaling to make it converge faster

- learning rates that are “too small” (slow) or “too big” (diverge)

It felt like a solid foundation.

So when I moved into deep learning, my default was still:

define a loss

compute gradients

run gradient descent

This month was when that mindset broke.

Because deep networks don’t just “optimize slowly”. They optimize in ways that feel like fighting the terrain.

June was about learning why plain gradient descent wasn’t enough — and why momentum and learning rate behavior are basically training infrastructure.

What you’ll learn

Why training can look “stuck” even when gradients exist — and how momentum + learning-rate control fixes that.

The 3 knobs in this post

- Batch size (noise level)

- Momentum (inertia / smoothing)

- Learning rate (step size)

How to use this post

Read it once, then reuse the debug checklist at the end whenever training feels weird.

The First Deep Learning Feeling: “Why is this not moving?”

May taught me that initialization can block learning before it starts.

June taught me that even when initialization is reasonable and gradients exist…

training can still feel stuck.

The loss decreases a bit. Then oscillates. Then plateaus. Then randomly improves again.

It didn’t feel like the clean, smooth convergence from 2016 exercises.

And that’s when I started hearing the same advice over and over:

- use stochastic or mini-batch updates

- add momentum

- be careful with learning rate schedules

This is where optimization got real.

- Noise: the loss wiggles because mini-batches are imperfect samples.

- Zig-zag: updates bounce between steep walls instead of moving forward.

- Plateaus: progress stalls in flat regions even though gradients technically exist.

Batch vs Stochastic: The Tradeoff I Finally Felt

In Andrew Ng’s course, I mostly lived in “batch gradient descent land”:

- compute gradient using all training examples

- take a clean step downhill

Deep learning training doesn’t work like that in practice.

It’s dominated by stochastic gradient descent (SGD) or mini-batch SGD:

- compute gradient from a subset of data

- take a noisy step

- repeat thousands of times

I knew this academically, but June is when I felt the consequences:

- the path is noisy

- the loss curve wiggles

- a single step can be “wrong” even if the trend is right

- Bigger batch: smoother loss curve, more stable steps, heavier compute per step.

- Smaller batch: noisier curve, more “jitter”, often faster learning early, but harder to judge step-by-step.

I stopped expecting the loss to drop every step.

I started asking: “Is the trend improving over a few hundred updates?”

That framing made the next concept click.

Momentum: The Simplest Trick That Changed My Intuition

Momentum is one of those ideas that sounds like a tweak.

Then you use it and it feels like the training process suddenly has inertia.

The way I internalized it:

- plain GD: “move based on the current gradient”

- momentum: “move based on a running direction, and let the gradient steer it”

So if the gradient keeps pointing roughly the same way for many steps, momentum accelerates progress.

If the gradient keeps flipping direction (noise / oscillation), momentum damps it.

This answered a practical question I kept running into:

Why does training bounce around so much even when the model is improving?

Momentum is basically a noise filter plus an accelerator.

Why Momentum Matters More in Deep Networks

In a shallow cost surface, gradients tend to be well-behaved.

In a deep network, I started imagining the loss surface as:

- steep in some directions

- flat in others

- curved in ways that create oscillation

- noisy because of mini-batches

That kind of terrain punishes plain gradient descent.

You get:

- zig-zagging

- slow progress in flat directions

- wasted steps canceling each other out

Momentum helps because it:

- reduces zig-zag

- accumulates progress in consistent directions

- makes training less sensitive to batch noise

So momentum isn’t an “optional improvement” in deep learning.

It’s survival gear.

Learning Rate: The Most Important Hyperparameter (Again)

I already learned in 2016 that learning rate matters.

But in deep learning, I learned a more frustrating truth:

With plain gradient descent, you can often pick a reasonable alpha and be okay.

With deep training, alpha feels like a control knob you need to monitor constantly:

- too small → you crawl forever and think the model is broken

- too large → you explode and think your gradients are wrong

- slightly wrong → you oscillate and plateau and waste days

Too low

Loss decreases, but so slowly you start doubting the whole setup.

Too high

Loss spikes, oscillates hard, or becomes NaN/Inf. Training feels unstable.

“Almost” right

Loss improves, then bounces/plateaus. Often needs momentum or a schedule to finish the job.

This month felt like learning rates became a first-class engineering concern.

The “Schedule” Idea: Alpha Doesn’t Have to Be Constant

This was a new mental leap for me.

In 2016, alpha was basically a constant I tuned.

Now I started absorbing the idea that:

- early training might need a larger learning rate to move quickly

- later training might need a smaller learning rate to settle

- sometimes you reduce alpha when improvement stalls

Even before I had a perfect toolchain, that idea felt obvious in hindsight:

If you’re far from the solution, you take bigger steps.

If you’re close, you take smaller steps.

Deep learning made that practical.

Start with a learning rate that moves

Early training should show clear progress within a reasonable number of updates.

Watch for the stall pattern

When improvement slows and the curve starts “hovering”, that’s a hint you may need smaller steps.

Reduce learning rate to settle

Lowering the rate later helps the model “land” instead of orbiting the solution.

How This Connects Back to 2016 ML (In a Useful Way)

This month made me appreciate how much of 2016 ML was secretly about optimization hygiene:

- feature scaling made GD work better

- diagnosing divergence was learning-rate debugging

- regularization changed the optimization landscape

- vectorization was about making optimization feasible at scale

Deep learning just pushes those concerns to the front.

So the connection is:

2017 is teaching me the operations of optimization.

2016 optimization mindset

Gradient descent felt like the algorithm. You tuned alpha, scaled features, and it converged.

2017 optimization mindset

Optimization feels like a system: noise, inertia, schedules, and stability all interact.

Same core idea: gradients and descent.

Different reality: training is noisy, fragile, and sensitive to control knobs.

My “Training Debug Checklist” (June Edition)

This month I started writing down a more disciplined loop.

Likely causes:

- learning rate too high or too low

- initialization issues First move:

- try a learning rate that’s clearly different (10x up or down) to see sensitivity

Likely causes:

- learning rate too high

- unstable gradients First move:

- reduce learning rate substantially

- add momentum only after stability returns

Likely causes:

- learning rate too low

- zig-zagging in steep directions First move:

- increase learning rate modestly

- add momentum to reduce wasted oscillation

Likely causes:

- learning rate slightly too high

- mini-batch noise + sharp curvature First move:

- reduce learning rate a bit

- add momentum to smooth the direction

Likely causes:

- initialization × learning rate interaction

- batch noise sensitivity First move:

- reduce learning rate

- make sure you’re not right on the edge of instability

It’s not perfect yet, but it’s already a better mental model than “maybe add layers”.

What Changed in My Thinking (June Takeaway)

Before June, I thought optimization was a solved piece: “compute gradients and descend.”

After June, I see it like this:

Optimization is not a single algorithm. It’s a set of dynamics you have to engineer.

Momentum and learning rates aren’t “extras”. They’re what makes deep learning training feel possible in practice.

What’s Next

By June, optimization finally felt under control — or at least less mysterious.

But something else was becoming obvious:

even with better optimizers, fully connected networks still struggled to make sense of images.

Next month, I turn to Convolutional Neural Networks and try to understand why they worked so much better for vision tasks — not because of better training tricks, but because of architectural bias.

July is about convolutions, locality, and why encoding domain structure into the model itself changed everything.

Convolutions - Why CNNs See the World Differently

After months wrestling with training stability, I finally hit the next wall - fully-connected nets don’t “get” images. Convolutions felt like the first time architecture itself encoded domain knowledge.

Initialization, Scale, and the Fragility of Deep Networks

After learning why gradients vanish, I discovered something even more unsettling - deep networks can fail before training even begins, simply because the starting scale is wrong.