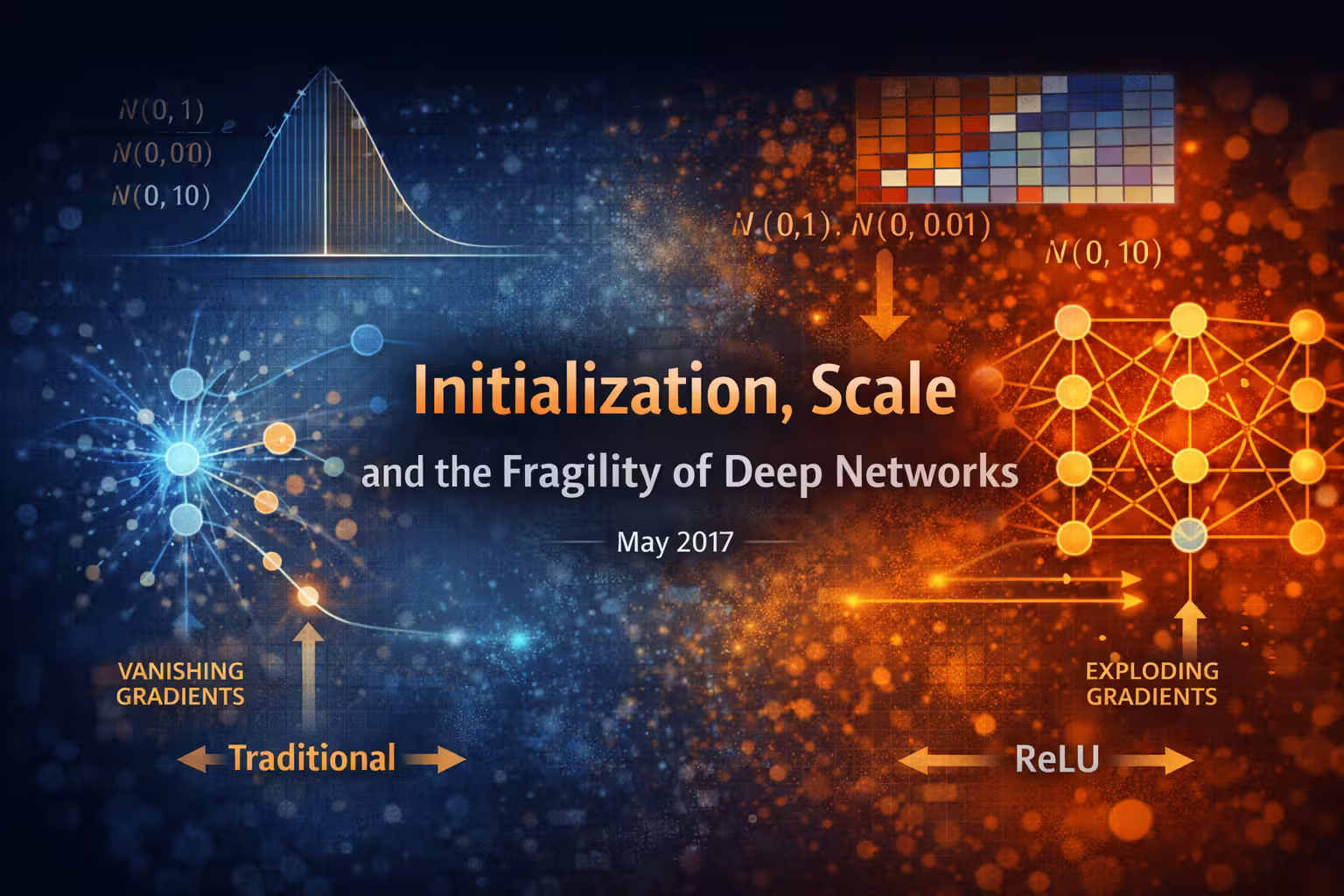

Initialization, Scale, and the Fragility of Deep Networks

After learning why gradients vanish, I discovered something even more unsettling - deep networks can fail before training even begins, simply because the starting scale is wrong.

Axel Domingues

In March I learned that deep networks can fail because gradients vanish or explode.

In April I learned ReLU helped gradients survive — at least in the active region.

So by May I was feeling optimistic.

I had this naive expectation:

If I use ReLU and backprop correctly, training should be mostly “fine”.

Then I hit a different kind of fragility:

initialization.

In classical ML, initialization is almost never a major plot point. With logistic regression, I can start weights at zero, run gradient descent, and it will move.

Deep networks are not like that.

What this post explains

Why deep nets can fail before training starts if weight scale is wrong.

The two flows to remember

Forward: inputs → activations → output

Backward: loss → gradients → early layers

Practical test you’ll learn

How to spot “bad scale” by watching activation/gradient magnitudes across layers.

In deep networks, the starting point can decide whether learning is even possible.

The First Surprise: Zero Initialization Is Not “Neutral”

My first instinct (from classical ML) was:

- if weights are unknown, start them at zero

That fails instantly in neural networks.

Not because the math breaks. But because the network becomes symmetric.

All neurons in a layer receive the same inputs and produce the same outputs. So they get the same gradients. So they stay identical forever.

You don’t get a “layer of neurons”. You get one neuron copied N times.

It produces identical neurons, which kills the point of having multiple units.

If all neurons start identical, they stay identical because they see the same inputs and receive the same updates. So the network can’t “specialize” units inside a layer.

If you print a few neurons’ weights during training and they remain extremely similar, you’re not really training “many units” — you’re training duplicates.

So randomness is necessary — not for performance, but to break symmetry.

The Second Surprise: Random Isn’t Enough

Okay, so I initialize randomly.

But then I discovered the real trap:

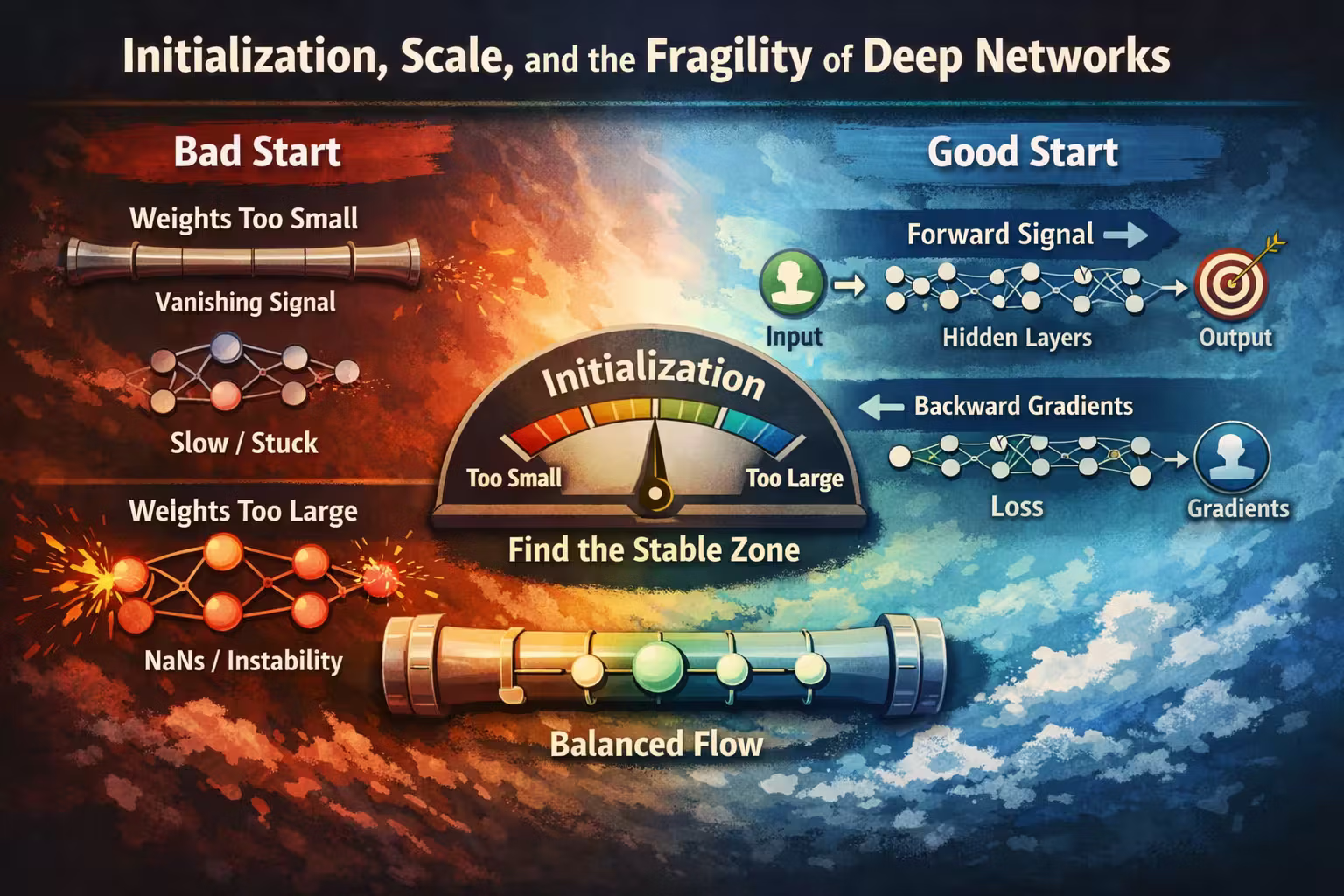

If the random weights are too small, signals shrink as they move forward. If the random weights are too large, signals explode as they move forward.

And the same happens to gradients moving backward.

Weights too small

Forward activations shrink layer-by-layer.

Backward gradients shrink layer-by-layer.

Result: learning becomes painfully slow or “stuck”.

Weights too large

Forward activations blow up.

Backward gradients blow up.

Result: instability, NaNs, wild loss jumps.

So initialization is about keeping values in a stable range as depth increases.

This is where deep learning started to feel like building a physical system:

- too much gain → instability

- too little gain → dead signal

- you need a stable operating point

A Mental Model That Helped: “Signal Preservation”

I started thinking about training as two flows happening simultaneously:

Forward flow:

- input → activations → output

Backward flow:

- loss → gradients → early layers

- Activations flow forward (inputs → output)

- Gradients flow backward (loss → early layers)

Initialization sets the initial “pipe size” for both flows.

If the scale is wrong:

- forward activations saturate or collapse

- backward gradients vanish or explode

- training becomes slow, unstable, or stuck

Why Depth Makes This Worse

With one layer, scale problems exist but are manageable.

With many layers, small distortions compound.

It’s the same story as March, but now before training even starts:

- each layer transforms the signal

- if each layer shrinks it slightly, depth kills it

- if each layer amplifies it slightly, depth blows it up

So the deeper the network, the more sensitive it becomes to scale.

This explains something I hadn’t fully appreciated before:

Deep learning progress wasn’t only “better ideas”.

It was also learning how to keep networks stable enough to train.

What I Learned About “Good” Initialization (In Plain Words)

I’m not trying to memorize formulas here. I’m trying to understand what the formulas are aiming for.

The goal of good initialization is:

- keep activation magnitudes roughly stable across layers

- keep gradient magnitudes roughly stable across layers

That’s the whole idea.

Different schemes (people are starting to standardize these in practice) try to pick initial weight distributions that preserve variance.

And the details differ depending on:

- activation function (sigmoid vs tanh vs ReLU)

- number of inputs/outputs to a layer

But the intent is always the same:

don’t let depth destroy the signal.

Start with a “boring” goal

At initialization, you want values to be:

- not collapsing to ~0

- not exploding to huge magnitudes

Watch what happens as depth increases

Pick a batch and check:

- do activations stay in a similar ballpark from early → late layers?

Also check the backward direction

During backprop, check:

- do gradients stay in a similar ballpark from loss-side → early layers?

If either direction collapses or explodes, training will feel fragile no matter what you do next.

ReLU Made Initialization Even More Important

ReLU has a nice property: it doesn’t saturate for positive values.

But it has another property that matters for initialization:

A ReLU neuron can output exactly 0 for negative inputs. If too many neurons output 0 early on, the network becomes sparse in a way that can slow learning.

So initialization interacts with:

- how many units are active

- how much signal passes forward

- how gradients flow back

Activation and initialization aren’t independent knobs.

ReLU changes how much signal survives forward (many zeros possible),

so initialization changes how many units even participate in learning early on.

If training looks sparse or “silent” early:

- check activation distributions (how many zeros?)

- check initialization scale

- check learning rate

This is the month where I stopped thinking of components separately.

Activation and initialization are coupled.

How This Connects Back to 2016 ML

In 2016, “scale” mattered mostly in one place:

feature scaling.

If features had wildly different ranges:

- gradient descent moved slowly

- convergence became unstable

- learning rate tuning became painful

So I learned:

- normalize features

- make the optimization surface friendlier

In deep learning, initialization is like feature scaling — but internal.

You’re not scaling the input. You’re scaling the entire chain of transformations so optimization has a chance.

Initialization makes deep models train at all.

That continuity helped: it’s still about optimization stability. But it’s now happening inside the model, layer by layer.

My Engineering Notes (What I Started Checking)

This month changed what I watch during “training”.

I started paying attention to:

- do activations blow up or collapse as depth increases?

- are most activations near zero all the time?

- do gradients become tiny in early layers?

- does training behave wildly differently between runs?

The last one was especially revealing.

If two runs with the same code behave totally differently, it’s usually:

- initialization scale

- learning rate scale

- or both

That’s when deep learning started feeling less like deterministic programming and more like controlled experimentation.

What Changed in My Thinking (May Takeaway)

Before May, I thought initialization was just a starting point — something training quickly “overwrites”.

After May, I understood something uncomfortable:

Initialization is not just where training starts. It shapes whether training can proceed through depth.

Deep networks are fragile.

They don’t fail loudly. They fail silently:

- by saturating

- by collapsing

- by starving gradients

- by turning “learning” into noise

May taught me that deep learning progress is a story of small practical stabilizers that unlock depth.

What’s Next

So far, the theme has been:

- March: gradients vanish/explode

- April: activations can protect gradients

- May: initialization can preserve signal

Next month I’m focusing on the next big stabilizer:

optimization improvements.

Gradient descent worked fine for my 2016 models. Deep networks make it feel inadequate.

June is about momentum, learning rate behavior, and why “just run gradient descent” stopped being good enough.

Optimization Got Real - Momentum, Learning Rates, and Why Plain Gradient Descent Wasn’t Enough

In 2016, gradient descent felt like “the algorithm.” In deep learning, it’s just the beginning. This month I learned why momentum and careful learning rates are what make training "actually move".

Activation Functions Are Not a Detail - ReLU Changed Everything

April 2017 — I used to treat activation functions like a minor math choice. Then I saw how one change (ReLU) could decide whether a deep network learns at all.