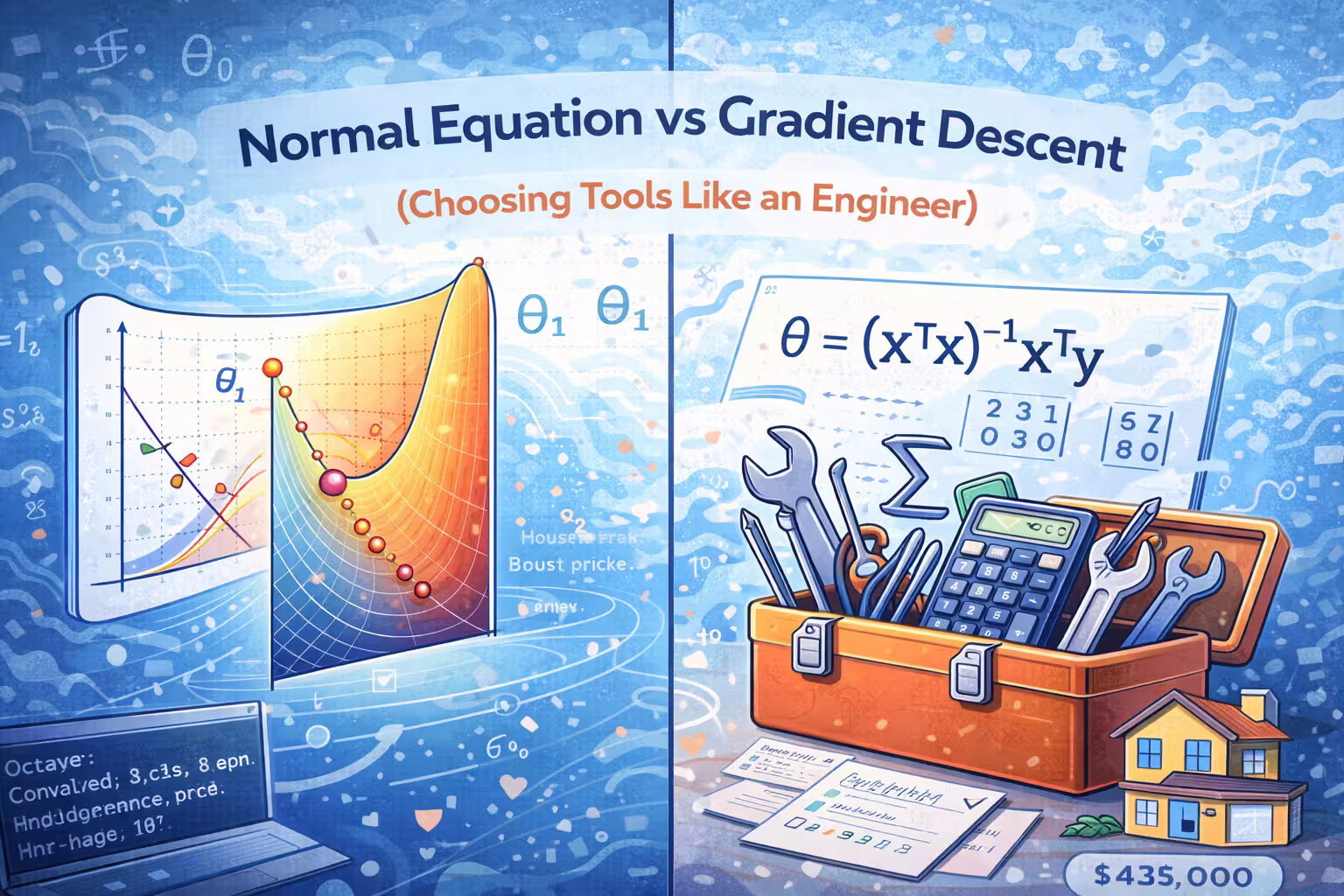

Normal Equation vs Gradient Descent (Choosing Tools Like an Engineer)

Notes — two ways to fit linear regression - iterative gradient descent vs one-shot normal equation. Same goal, different tradeoffs.

Axel Domingues

After implementing linear regression with gradient descent (single variable, then multiple variables), I hit the most “engineer” question in the course:

If two methods solve the same problem, how do I pick the right one?

In this part of Andrew Ng’s ML course, linear regression can be trained using either:

- Gradient Descent (iterative optimization)

- Normal Equation (solve for parameters in one shot)

Both produce theta (the parameter vector). Both can predict y from X. But the developer experience and operational tradeoffs are totally different.

If you want the simplest path

Use Normal Equation for small linear regression problems. It’s one-shot and deterministic.

If you want the reusable skill

Use Gradient Descent. It generalizes to logistic regression, neural nets, and most of the course.

The “gotcha” to remember

If gradient descent feels broken, it’s often feature scale (or alpha) — not your math.

Same model, two training strategies

No matter which training method you choose, the prediction step is the same:

predictions = X * theta;

theta you can use for prediction.What changes is how you get theta:

- Gradient descent: a learning process you can observe (cost over time)

- Normal equation: a one-shot solve that gives you theta immediately

Option A — Gradient Descent

Gradient descent starts from an initial theta (often zeros) and updates it step-by-step.

What you implement

In Octave, a typical vectorized update loop looks like this:

for iter = 1:num_iters

errors = (X * theta) - y;

theta = theta - (alpha/m) * (X' * errors);

J_history(iter) = computeCostMulti(X, y, theta);

end

Why it’s used

- Works for many models, not just linear regression

- Scales to large feature sets (where one-shot matrix operations get expensive)

- Teaches you how optimization behaves

What can go wrong

- you need to choose a good

alpha - you often need feature normalization

- convergence can be slow or unstable without telemetry

Treat J_history like logs. If you can’t see whether cost is decreasing, you’re guessing.

Option B — Normal Equation

The normal equation computes theta directly (no iterations).

In Octave, the common implementation uses the pseudo-inverse:

theta = pinv(X' * X) * X' * y;

Why it feels great

- no learning rate to tune

- no iterations

- no “is it converging?” anxiety

What can go wrong

- computing

X' * Xand inverting/solving it becomes expensive as feature count grows - you can run into numerical issues if features are highly correlated (the pseudo-inverse helps)

The course typically recommends pinv instead of directly computing an inverse. pinv is more numerically stable and works better when matrices are not nicely invertible.

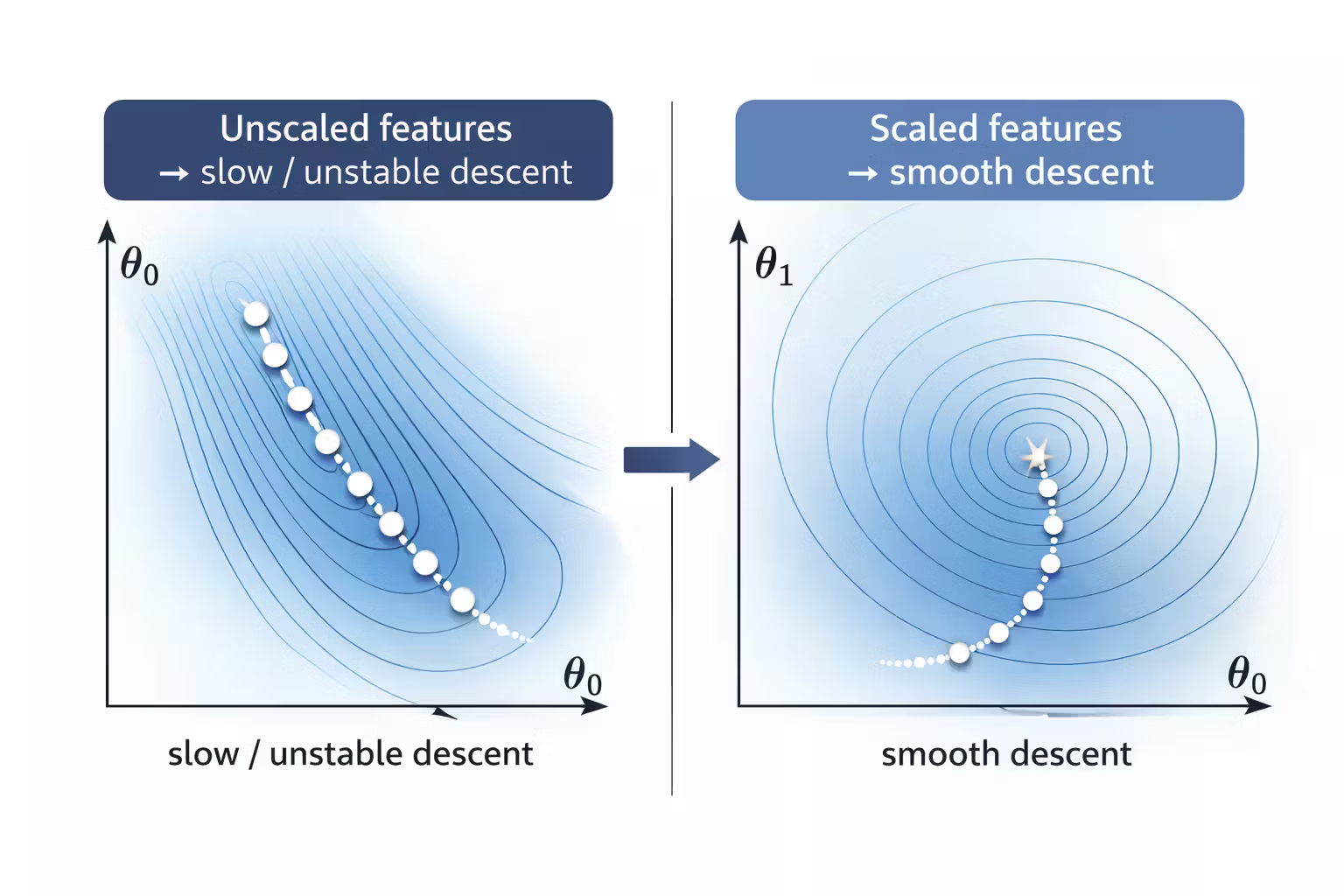

Feature scaling: the biggest practical difference

This is one of the most useful rules of thumb I took from the course:

- Gradient descent usually benefits massively from feature normalization.

- Normal equation does not require feature normalization to converge (because it doesn’t iterate).

That said, scaling can still be helpful for interpretability and numerical conditioning, but it’s not a hard requirement the way it is with gradient descent.

If gradient descent “doesn’t learn,” check feature scales first. The most common failure mode is mixing features with very different ranges.

Choosing like an engineer

Here’s how I frame the choice in practice.

Decision table

| Question | Gradient Descent | Normal Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Do I want a general optimization tool I can reuse later? | ✅ Yes | ❌ Not really |

| Do I want the simplest path for small linear regression problems? | ⚠️ Maybe | ✅ Yes |

Do I want to avoid tuning alpha? | ❌ No | ✅ Yes |

| Do I have lots of features? | ✅ Better | ⚠️ Can get expensive |

| Do I want training telemetry and control? | ✅ Yes | ⚠️ Less relevant |

Rule of thumb

- If the problem is small and strictly linear regression, normal equation is a clean baseline.

- If I want a workflow that generalizes to other models (logistic regression, neural nets), gradient descent is the habit-builder.

How I compare them (a practical workflow)

Normalize features (only for gradient descent)

Run featureNormalize and keep mu / sigma so you can normalize future inputs the same way.

Train with gradient descent

Pick alpha + num_iters, and watch J_history. If it’s not decreasing, stop and fix scaling/alpha.

Train with the normal equation

Compute theta using pinv. No tuning, no iterations.

Compare predictions on the same inputs

Use identical feature ordering. If the predictions are close, your pipeline is probably correct.

Operational thinking (even in coursework)

This is where I started thinking beyond the math.

Monitoring

- Gradient descent gives you a built-in health signal: cost over time.

- Normal equation is “silent” — you get a theta, but you don’t observe a learning process.

Reproducibility

- Gradient descent depends on

alpha, iterations, and initialization. - Normal equation is deterministic given

Xandy.

Performance

- Gradient descent cost per iteration is predictable.

- Normal equation can be fast for small

n, but becomes heavy asngrows.

The method that’s simplest for a homework dataset might not be simplest in production. Production constraints usually push you toward iterative methods and good monitoring.

What I’m keeping from this lesson

- “One-shot” vs “iterative” is a recurring theme in engineering.

- Normal equation is a great baseline for small linear regression.

- Gradient descent is the reusable tool that unlocks most of the course.

- Telemetry matters: if you can’t observe training behavior, debugging gets expensive.

What’s Next

Next up is my first real classifier: Logistic Regression.

I’ll predict admissions from exam scores, then push into a non-linear dataset and learn why regularization is the difference between a model that generalizes and one that memorizes.

Exercise 2 - Logistic Regression for Classification (My First Real Classifier)

My first real classifier - predict admissions from exam scores with logistic regression, then learn why regularization matters on a non-linear dataset.

Linear Regression With Multiple Variables (and Why Vectorization Matters)

Notes from Andrew Ng’s ML course — extend linear regression to multiple features, learn feature scaling/mean normalization, and stop writing slow loops by vectorizing everything.