Hallucinations: A Probabilistic Failure Mode, Not a Moral Defect

Hallucinations aren’t “the model lying”. They’re what happens when a probabilistic engine is forced to answer without enough grounding. This post is about designing products that stay truthful anyway.

Axel Domingues

If you’ve shipped anything with an LLM in it, you’ve had that moment:

A clean demo. A happy stakeholder. A confident answer.

And then… the model invents a policy, a product feature, a citation, or a number that simply doesn’t exist.

People call this “lying”.

Engineers call it “unreliable”.

But the right mental model is neither moral nor mystical:

Hallucination is a probabilistic failure mode.

It’s what happens when a system optimized to produce plausible continuations is asked to be a truth machine — without being given the constraints, grounding, or verification loops that truth requires.

This month is about shifting the conversation from blame to design.

The goal is to design products that stay correct even when a component is allowed to be probabilistic.

The goal this month

Treat hallucinations like a reliability problem: define truth boundaries, add grounding, and measure failure rates.

The mindset shift

Stop asking “How do I prompt it to be honest?”

Start asking “What must never be wrong, and how do we enforce that?”

What I’m measuring

Not “vibes”.

Unsupported-claim rate, citation coverage, abstention rate, and tool mismatch.

What counts as progress

The system either:

- returns a grounded answer, or

- safely refuses / escalates

…and it does this reliably across variants.

The Model Doesn’t “Know” — It Predicts

Hallucination feels shocking because humans assume a hidden “truth module”:

- you either know something, or you don’t

- and if you answer confidently while wrong, you’re lying

LLMs don’t work like that.

They are trained to minimize surprise:

given a context, produce the next token that is statistically likely.

So when the context doesn’t contain enough evidence, the model does what it was trained to do:

it fills in the most likely continuation.

Sometimes that continuation is true.

Sometimes it’s a very convincing imitation of truth.

That’s why hallucinations often look like:

- a plausible-sounding policy name

- a realistic-but-fake citation

- a familiar pattern (“this company probably has a VP of X”) applied to the wrong entity

- a number that “feels right” given the surrounding text

This is not a character flaw.

It’s the default behavior of a completion engine operating without constraints.

It’s giving the system a source of truth and a way to enforce it.

A Practical Definition: “Unsupported Claims”

The cleanest engineering definition I’ve found is:

A hallucination is an output that contains claims not supported by available evidence.

That definition matters because it gives you a handle for design:

- What evidence was available at generation time?

- Was the model required to cite it?

- Was there a validator?

- Was “I don’t know” allowed?

If you can’t answer those questions, you don’t have a hallucination problem.

You have an architecture problem.

- Grounding: tying outputs to verifiable sources (docs, DBs, tools, retrieval).

- Abstention: allowing the model to say “I don’t know / not enough info” and treating that as success.

- Faithfulness: whether an answer reflects the provided sources (not just being correct by luck).

- Calibration: whether confidence matches correctness (rarely perfect, but measurable).

- Constraint: a mechanism that prevents invalid output (schemas, validators, tool calls, policies).

Why Hallucinations Happen (Predictably)

If you’ve debugged distributed systems, hallucinations will feel familiar.

They’re not random. They cluster around specific conditions.

1) The prompt implies an answer must exist

Users ask like this:

“What is the refund policy for plan X?”

The model reads “refund policy exists” + “plan X exists” and continues accordingly.

2) The system rewards fluency over truth

If your UI or evaluation only cares about “helpfulness” and “tone”, you’re selecting for confident completion.

3) The model is out of distribution

Your company, your internal tools, last week’s incident, your product’s edge cases — these are rarely in pretraining.

So the model “generalizes” using nearby patterns.

4) The task is under-specified

Ambiguous questions create a vacuum. LLMs don’t like vacuums.

5) You forced it to reason without anchors

Long chains of reasoning can accumulate small errors and then defend them fluently.

Fluent reasoning is not evidence.

It’s just another form of plausible continuation.

A Taxonomy That Matters in Production

“Hallucination” is too broad to debug.

In production, you want failure categories that map to mitigations.

What it looks like: a policy, number, feature, or event that doesn’t exist.

What usually fixes it: grounding (RAG/tools) + “abstain allowed” + claim-level checks.

What it looks like: the model mixes two similar entities (two products, two companies, two incidents).

What usually fixes it: entity resolution + stricter context assembly + retrieval with IDs (not fuzzy names).

What it looks like: citations that look formatted but don’t correspond to real sources.

What usually fixes it: tool-based citation (only cite retrieved documents) + validators (URLs must exist / be in corpus).

What it looks like: “I checked the database and…” without any tool call.

What usually fixes it: enforce “tool use or say you didn’t” + require structured tool outputs + block tool-free claims.

What it looks like: answers that should be probabilistic, stated as certain.

What usually fixes it: calibrate UI (“likely”, “I’m not sure”) + preference tuning + policies that force uncertainty language.

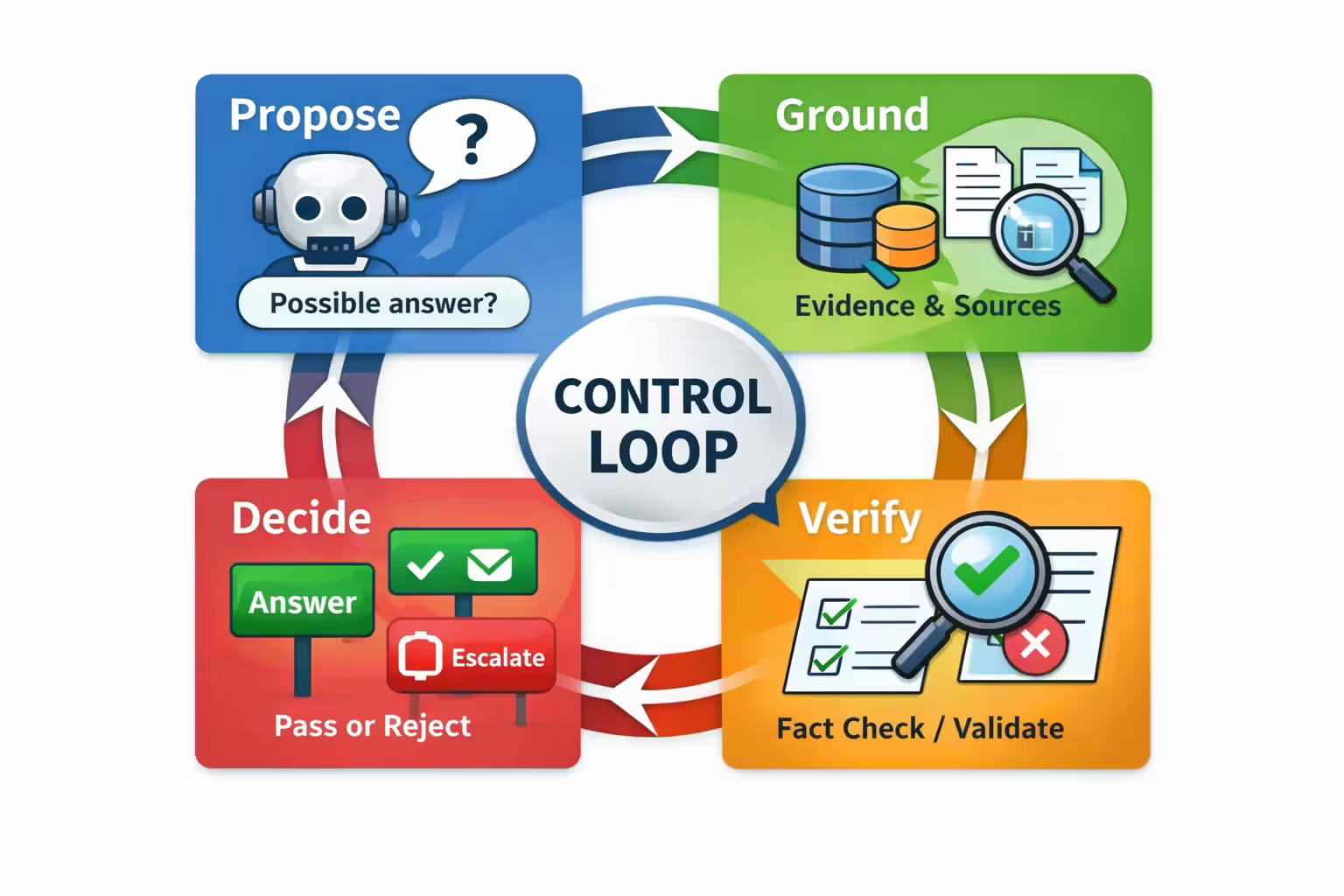

Hallucinations Are a Control Problem

Here’s the big architectural move:

Stop treating an LLM response as a final artifact.

Treat it as the first stage of a control loop.

- The model proposes.

- The system grounds.

- The system verifies.

- The system decides whether to answer, abstain, or escalate.

Once you see hallucinations as control, the usual mitigations become clearer:

- RAG isn’t “a feature”. It’s a sensor (evidence input).

- Validators aren’t “extra code”. They’re actuators (constraint enforcement).

- Abstention isn’t “bad UX”. It’s stability.

Reliability slogan (August 2023)

A probabilistic component is safe when the system can refuse to act on its uncertainty.

Define Your Truth Boundaries First

Before picking techniques, decide what your product is allowed to be wrong about.

In other words:

where is the truth boundary?

Here’s a useful way to classify outputs:

Free-form generation

Marketing copy, brainstorming, tone rewrites.

Hallucination is usually acceptable (low stakes).

Knowledge claims

Answers that imply facts about your business, users, policies, or the world.

Hallucination must be bounded.

Recommendations & decisions

Anything that guides user action (pricing, eligibility, compliance).

Needs evidence + policy constraints.

Actions in the world

Tool calls that change state (refund, cancel, deploy, email, pay).

Requires hard validation + audit + safe defaults.

Notice the key transition:

The more state and money you touch, the less “model output” is allowed to be authoritative.

The Architecture Patterns That Actually Work

This is the part senior engineers care about: what survives production.

Pattern 1: Retrieval-grounded answers (with faithfulness checks)

You don’t ask the model to “remember” the truth. You retrieve it.

Then you require the answer to be supported by the retrieved evidence.

Minimum viable rules that help immediately:

- answer must cite at least one retrieved source for every knowledge claim

- citations must come from tools, not from the model “inventing” them

- if retrieval returns nothing, the system should abstain

Abstention is a feature.

It prevents confident nonsense.

Pattern 2: Tool-first for factual queries

If the question has a canonical answer in a system:

- DB

- CRM

- pricing service

- policy engine

- configuration repo

…then the model should not guess.

It should call the tool, read the result, and summarize.

Pattern 3: Schema + validators for structured output

The most underrated hallucination killer is:

make the output format strict.

Examples:

- JSON schema

- enum-limited fields

- regex-constrained IDs

- type-checked tool inputs

If the model produces invalid structure, you retry or fail safe.

This doesn’t make the model “smart”.

It makes the system operable.

Pattern 4: “Propose, then verify” for high-stakes flows

For high-stakes answers:

- first pass generates a draft

- second pass extracts atomic claims

- external checker validates claims against tools/sources

- only then do you present a final response

If correctness matters, your verifier must be anchored to external truth.

How to Measure Hallucinations Without Turning It Into a Philosophy Debate

You can’t improve what you can’t measure.

So don’t measure “hallucination”.

Measure observable proxies.

Offline evaluation

A curated set of prompts with expected behaviors:

- correct answer

- grounded citation

- safe abstention

Run it on every model or prompt change.

Online telemetry

Track production signals:

- citation coverage

- tool mismatch rate

- “no evidence” abstention rate

- user correction events

- escalation rates

Practical metrics I’ve used (and like)

- Unsupported-claim rate: fraction of outputs with at least one claim not grounded in sources/tools.

- Citation coverage: percentage of sentences/claims with attached evidence.

- Abstention correctness: when the model abstains, was it right to abstain?

- Tool mismatch: model summary contradicts tool output.

- Edit distance to correction: how often users rewrite the answer or immediately ask “are you sure?”

This is why I keep saying hallucinations are an architecture problem.

The Misleading Fixes (And What They Actually Do)

“Just lower temperature”

Lower temperature reduces randomness.

It often reduces hallucinations.

It also tends to:

- make answers more repetitive

- increase “safe” generic replies

- hide uncertainty under confident-sounding boilerplate

Use it, but don’t confuse it with correctness.

“Just make the prompt stricter”

Prompts help.

But if the system has no grounding, the model will still fill gaps — just in a more polite tone.

“Just use a bigger model”

Bigger models typically hallucinate less in some regimes.

They also:

- cost more

- are not immune

- may become more persuasive when wrong

The more fluent the model, the more dangerous ungrounded answers can be.

A Simple Playbook for Teams Shipping LLM Features

If I had to compress this month into a playbook, it’s this:

Map truth boundaries

List the output types your product generates and mark what must never be wrong.

Route facts through truth sources

Prefer tools and retrieval for factual claims. Don’t let the model “remember” production truth.

Require evidence

Make citations and tool outputs mandatory where knowledge claims exist.

Allow abstention

Design “I don’t know” as a success path. Wire escalation/handoff.

Validate and fail safe

Use schemas, validators, and policy gates. If checks fail, retry or refuse.

Measure continuously

Build an eval set and production telemetry. Treat hallucination rates like error budgets.

This is what “LLMs in production” looks like when you’re not doing demos.

It’s not magic.

It’s engineering.

Resources

FAQ

No.

“Lying” implies intent. Hallucination is what a probabilistic generator does when it needs to continue text but lacks grounding.

Treat it like any other reliability issue: define constraints, add verification, and measure the failure rate.

It reduces some types — especially fabrication — but it introduces new failure modes:

- retrieval returns irrelevant docs

- the model ignores the retrieved evidence

- the model mixes sources (conflation)

RAG helps when you also measure faithfulness and enforce evidence requirements.

No.

If you don’t allow abstention, you’re rewarding hallucination.

A safe system has a success path where the model can say:

- “not enough information”

- “I need to check a source”

- “escalate to a human”

They can help, but they’re not proof.

A model can produce a fluent “verification” that is itself ungrounded. For high-stakes systems, verification must reference external truth (tools, retrieval corpora, policies).

What’s Next

July was about the product architecture around an LLM.

August is the dark side of that architecture: what happens when the model is forced to speak without truth constraints.

Next month we turn the “grounding” knob all the way up:

RAG Done Right: Knowledge, Grounding, and Evaluation That Isn’t Vibes

Because the real job isn’t generating text.

It’s making sure the generated text is allowed to become product truth.

RAG Done Right: Knowledge, Grounding, and Evaluation That Isn’t Vibes

RAG isn’t “add a vector DB.” It’s a reliability architecture: define truth boundaries, build a testable retrieval pipeline, and evaluate groundedness like you mean it.

Dissecting ChatGPT: The Product Architecture Around the Model

ChatGPT isn’t “an LLM”. It’s a carefully designed product loop: context assembly, policy layers, tool orchestration, and observability wrapped around a probabilistic core.