Dissecting ChatGPT: The Product Architecture Around the Model

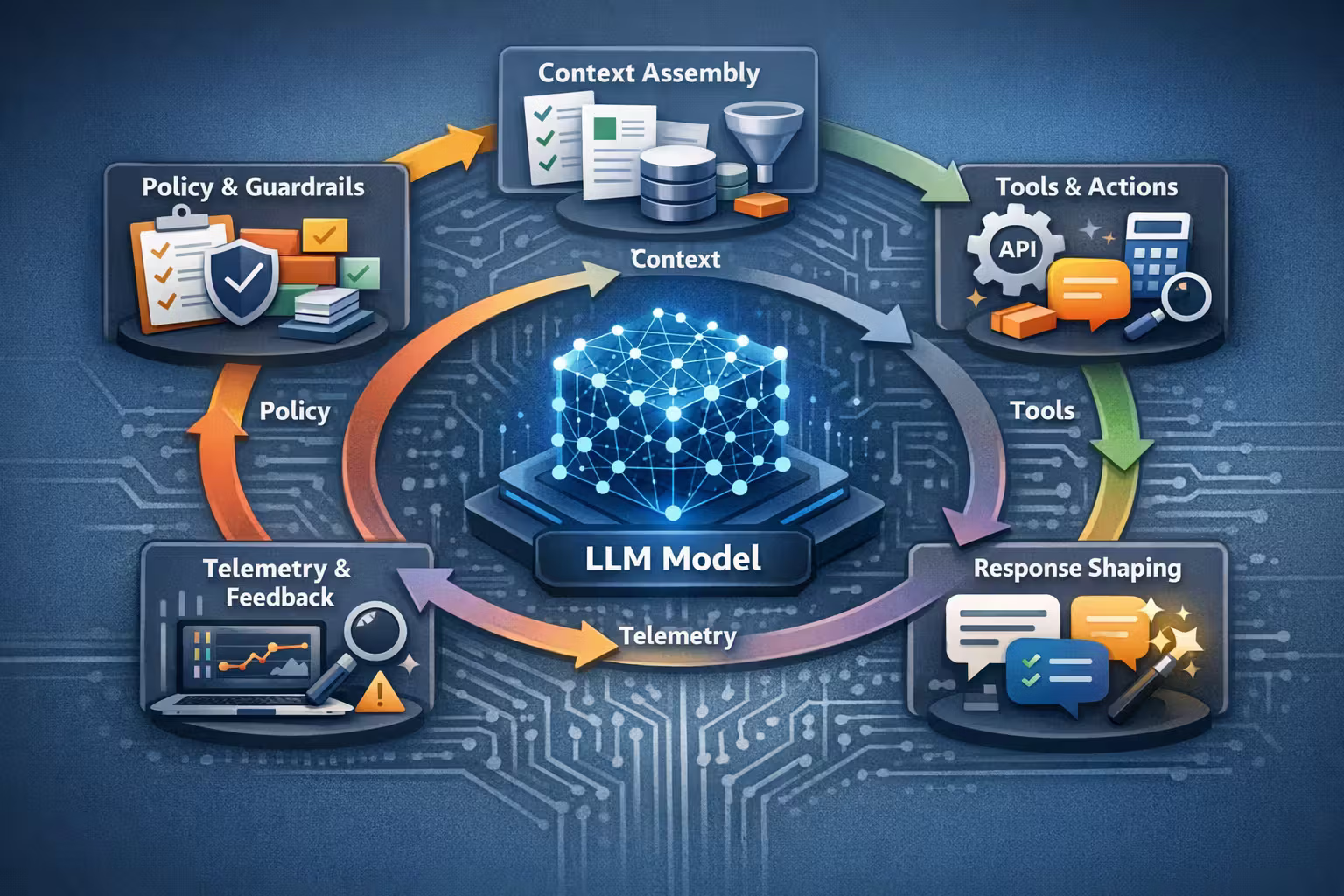

ChatGPT isn’t “an LLM”. It’s a carefully designed product loop: context assembly, policy layers, tool orchestration, and observability wrapped around a probabilistic core.

Axel Domingues

If you’ve ever tried to “just add an LLM” to a real product, you’ve felt it:

The demo works.

Then reality shows up.

- the model answers confidently with no grounding

- the user asks a question that requires state or permissions

- a tool call succeeds but the user never sees it

- latency spikes, cost spikes, and now you’re in incident mode

- prompt injection lands, and suddenly the model is executing the user’s instructions

This is why I like to say:

ChatGPT is not a model.

It’s a product architecture wrapped around a model.

And that distinction matters, because that architecture is what makes the system feel coherent, safe-ish, and usable.

a completion engine into a product:

- context assembly

- instruction hierarchy

- tool orchestration

- policy and safety layers

- observability + evals

- rollout and regression discipline

The core idea

The model is a probabilistic CPU.

ChatGPT is the runtime around it.

The mistake teams make

They ship one API call and call it “AI”.

Then they discover they shipped a stochastic production bug.

What you’ll take away

A practical architecture blueprint you can copy:

components, boundaries, and failure modes.

The framing

Reliability isn’t a model property.

It’s a system design outcome.

ChatGPT as a product loop (not a single inference)

Most people picture this:

user prompt → model → answer

Real systems look closer to this:

request → policy → context assembly → model → (tools) → model → response shaping → logging → feedback loop

You can think of it like a modern full-stack runtime:

- a scheduler (when and how the model runs)

- a memory system (what context gets injected)

- an IO layer (tools / retrieval / browsing / code execution)

- a permission system (what the model is allowed to do)

- a debugging surface (traces, token usage, evals, regressions)

The model is only one step inside it.

The prompt stack is a policy stack

Chat-style systems aren’t “prompted” once. They’re programmed continuously.

In practice, ChatGPT-like products have layers of instruction, typically in this shape:

- System instructions: the product’s non-negotiables (identity, safety posture, formatting, tool rules)

- Developer instructions: the app’s task framing (role, output schema, domain constraints)

- User instructions: the user’s request (which can be malformed, malicious, or ambiguous)

- Tool results: structured state from the outside world (retrieval, APIs, calculations)

The critical point:

Not all instructions are equal.

You need an explicit hierarchy, because users will try to override your system (sometimes accidentally, sometimes not).

You have an untrusted program input with no sandbox.

- Prompt stack: the ordered bundle of instructions and context fed to the model.

- Context assembly: the logic that selects, compresses, and injects relevant information into the prompt.

- Tool loop: a multi-step flow where the model proposes actions, tools execute them, and results return to the model.

- Guardrails: rules and checks outside the model that constrain inputs, tools, and outputs.

- Eval harness: repeatable tests that catch regressions as prompts, models, or data change.

Context assembly is the “real work” nobody budgets for

Most failures I see in production are not “bad model”.

They are bad context.

The model can only reason over what you give it in the window:

- missing facts → confident hallucination

- too many facts → the wrong ones win

- stale facts → wrong answers with high confidence

- sensitive facts → privacy incident

So the product needs a context assembly pipeline that behaves like an engineered subsystem, not a prompt hack.

The hard constraint

The context window is finite.

You’re building a budgeted memory system.

The hidden job

Select what matters now, for this user,

under this permission model.

The failure mode

Wrong context looks like “the model is dumb”.

It’s usually a retrieval + ranking bug.

The fix

Treat context assembly like search + caching:

instrument it, test it, and version it.

Define context sources (and classify them)

Typical sources:

- conversation history (short-term memory)

- user profile / preferences (long-term memory)

- product data (documents, tickets, knowledge base)

- live state (orders, inventory, account status)

- policy constraints (what must be true, what must not be leaked)

Put permissions in the assembler, not in the model

The model is not your auth system.

- the assembler decides what can be included

- tools decide what can be fetched

- the model gets only what it is allowed to see

Rank and compress aggressively

You will always have more candidate context than window space. Use:

- retrieval + reranking

- summarization with provenance

- “recency + relevance” strategies

- hard caps per source (so one source can’t monopolize the window)

Log the assembled prompt (or a safe representation)

If you can’t answer “what did the model see?”, you can’t debug anything. Store:

- IDs of retrieved chunks

- ranking scores

- token counts per section

- redaction decisions

Version the assembly logic

This is software. Treat changes like API changes:

- diffs

- rollouts

- regression tests

It won’t. It can’t.

Tools are side effects: treat them like production IO

Tool use is where LLM apps stop being “chat” and start being systems.

If the model can:

- send an email

- trigger a refund

- deploy infrastructure

- modify a database record

…then you are building a stochastic actor in your production environment.

That’s not scary if you treat tool use like any other side-effectful architecture:

capabilities, permissions, idempotency, and observability.

Capability design

Tools should be small and explicit.

One tool = one intention.

Permission design

Use allowlists and scoped tokens.

No “god tools”.

Reliability design

Idempotency keys, retries, timeouts,

and safe fallbacks.

Explainability design

Show the user what happened:

tool calls, results, and confidence.

If it can charge money, delete data, or change permissions, you need an explicit human-in-the-loop step.

Safety is layered: policy outside the model is not optional

ChatGPT-like products generally rely on multiple layers, because no single layer is perfect.

At a high level, you want defense in depth:

- Input checks: detect disallowed content, sensitive data, injection patterns, weird payloads

- Prompt-level policy: explicit safety posture and tool rules

- Tool sandboxing: scoped credentials, constrained schemas, rate limits, audit logs

- Output checks: refuse, redact, or reformat responses that violate constraints

- Product UX: nudges, confirmations, citations, “I don’t know” patterns

The key mental shift is this:

Safety is an engineering discipline, not a moral posture.

It’s about bounding failure modes.

- it constrains what the system can do

- it detects violations

- it forces fallback behavior

Observability: treat the LLM layer like a distributed system

By July 2023, my strongest opinion about LLM products is simple:

If you can’t trace it, you can’t ship it.

In classic systems, we ask:

- what request path was taken?

- what dependencies were called?

- where did latency occur?

- what error rates spiked?

LLM systems need the same, plus LLM-specific signals:

- token counts (prompt / completion / total)

- model selection (which model, which version)

- context sources (what was retrieved and why)

- tool calls (which ones, params, outcomes)

- refusal / safety events (what was blocked)

- user feedback (thumbs down, edits, retries)

A trace should let you answer:

- what did we show the model?

- what did the model do next?

- what tools did we run?

- what did the user actually experience?

A reference architecture you can steal

Here’s the “boring” architecture that tends to work.

Not because it’s fancy.

Because it makes responsibilities explicit.

API Gateway

Auth, rate limits, tenant isolation, request validation.

Orchestrator

Runs the loop: assemble context → call model → call tools → shape response.

Context Service

Retrieval, ranking, compression, redaction, provenance, caching.

Tool Runner

Executes tool calls in a sandbox: timeouts, retries, idempotency, audit logs.

Safety Service

Input/output policy checks, injection defenses, sensitive data redaction.

Model Gateway

Model routing, fallbacks, quotas, streaming, caching, version pinning.

Telemetry + Tracing

Token/latency/cost metrics, structured traces, sampling, alerting.

Eval Harness

Offline tests + golden sets + regression detection for prompts and models.

The product decisions that matter more than the model

If you’re building something ChatGPT-like inside your domain, these are the decisions that usually dominate outcome:

Bad: shove the whole conversation forever.

Worse: summarize without provenance.

Better: separate memory into layers:

- short-term: recent messages, tightly bounded

- long-term: explicit user preferences and stable facts (with a clear UI)

- domain knowledge: retrieved on demand (RAG), not stored in the chat thread

And always log what was injected.

You need product patterns that make “I’m not sure” usable:

- citations / sources when available

- “here’s what I know” vs “here’s what I’m inferring”

- clarification questions (when safe and cheap)

- safe fallback: “I can’t answer that reliably; here are the next best actions”

Treat tools like capabilities:

- allowlist tools per feature

- enforce schemas strictly

- gate irreversible actions with confirmation

- idempotency keys for money/data changes

- timeouts and graceful degradation

Prompts, retrieval logic, and model versions all behave like code changes.

So ship them like code:

- canary releases

- feature flags per tenant

- rollback by version pinning

- regression evals before rollout

- monitoring during rollout

Anti-patterns (and how they fail in production)

1) “One big prompt”

You paste policies, product docs, and the user request into a single blob.

It works until it doesn’t:

- the window fills

- the wrong instruction wins

- your policies become “optional”

Fix: split responsibilities:

- policy layer

- context assembly layer

- tool layer

- response layer

2) “The model can just call the API”

You give the model broad access and trust it to behave.

It works until it doesn’t:

- it calls tools with wrong parameters

- it leaks data across tenants

- it performs actions the user didn’t authorize

Fix: tools as capabilities + sandbox + audit + confirmation boundaries.

3) “We’ll add evals later”

You won’t. You’ll drift slowly until you have no idea why quality changed.

Fix: minimum viable eval harness before you scale usage.

That’s not a strategy.

Resources

ChatGPT (product)

Useful as a reference point for how a chat product can feel coherent when the model is inherently probabilistic.

InstructGPT / RLHF (paper)

A readable view of the “assistant tuning” pipeline and why preference optimization changes behavior.

FAQ

You can replicate the principles:

- context assembly as a first-class system

- strict instruction hierarchy

- tools as sandboxed capabilities

- evals + telemetry as the minimum bar

- rollouts with version pinning and rollback

The specific internals will differ, but the design constraints are universal.

A traceable orchestrator + a tiny context assembler.

If you can’t answer “what did the model see?” you’re blind. If you can’t control what context enters, you’ll hallucinate by default.

Not always. Tools increase capability and risk.

If you start without tools, design the architecture so tool support can be added later:

- explicit orchestrator

- structured intermediate state

- safety and permission layers that already exist

Treat it like control theory applied to behavior:

- you shape the policy with constraints and feedback

- you observe drift and failure modes

- you correct via tuning, prompts, and product guardrails

Alignment is not a sticker you put on a model — it’s a control system.

What’s Next

Now that we’ve treated ChatGPT as a product runtime, we can talk about the most visible user-facing failure mode of that runtime:

hallucinations.

Next month:

Hallucinations: A Probabilistic Failure Mode, Not a Moral Defect

The goal is to replace outrage with engineering:

- why hallucinations happen structurally

- what makes them worse (bad context, bad incentives, ambiguous tasks)

- and what practical guardrails reduce them in real products

Hallucinations: A Probabilistic Failure Mode, Not a Moral Defect

Hallucinations aren’t “the model lying”. They’re what happens when a probabilistic engine is forced to answer without enough grounding. This post is about designing products that stay truthful anyway.

RLHF: Stabilizing Behavior with Preferences (Alignment as Control)

RLHF is best understood as control engineering: a learned reward signal plus a constraint that keeps the model near its pretrained competence. Here’s how it works and how it fails.