GPAI Obligations Begin: What Changes for Model Providers and Enterprises

The EU AI Act turns “model choice” into a regulated interface. This month is a practical playbook: what GPAI providers must ship, what enterprises must demand, and how to build compliance into your agent platform without slowing delivery.

Axel Domingues

Last month was security for connectors.

This month is what happens when security stops being “best practice”… and becomes a regulated contract boundary.

Because in late 2025, “pick an LLM provider” is no longer just a technical decision.

It’s a compliance decision.

And that changes the architecture.

Not in a philosophical way.

In a boring, operational way:

- you need inventories

- you need controls you can prove

- you need logs you can retrieve

- you need incident runbooks

- you need vendor packets you can version

- you need a governance surface that matches the reality of agentic systems

This post is about the moment GPAI obligations begin—and what it forces model providers and enterprises to change.

The point is to translate obligations into interfaces, artifacts, and operational controls you can ship.

- Aug 2, 2025: GPAI model obligations become legally binding.

- Aug 2, 2026: GPAI obligations become enforceable for new GPAI models placed on the market after the grace period.

- Aug 2, 2027: the grace period ends for existing GPAI models.

- Late 2025 (expected): a voluntary Code of Practice is intended to help providers demonstrate compliance with the GPAI rules.

The shift this month

Regulation turns the model layer into a governed supply chain.

The core design insight

Compliance isn’t paperwork.

It’s a control plane you build into the platform.

The practical outcome

Providers must ship evidence + instructions.

Enterprises must ingest + enforce them.

The failure mode to avoid

Treating compliance as a “doc sprint” after launch.

First: What “GPAI obligations” really means in practice

“GPAI” (General-Purpose AI) is the foundation model layer: models that can be used across many tasks and then adapted downstream.

That matters because this layer behaves like a platform dependency, not a feature:

- it updates frequently

- it’s probabilistic

- it’s used across many products

- its failure modes are non-local (a single model change can break many workflows)

So the AI Act-era move is predictable:

If a component is a platform dependency, it gets a governance interface.

The governance interface isn’t just “security.”

It’s documentation, transparency, and post-market monitoring as a routine part of operating the model.

The big reframing

Before:

- “We integrated an LLM API.”

After:

- “We integrated a regulated upstream component with obligations, evidence, and monitoring expectations.”

That framing is what stops this from turning into chaos.

Providers vs enterprises: two different kinds of work

This post is split into two tracks:

- Model providers (GPAI providers): what you must produce (artifacts + controls) and how you operate them.

- Enterprises (deployers/builders): what you must demand, store, and enforce when you build products on top of GPAI.

Because most teams lose a year by mixing these up.

You become a platform operator for downstream teams.

The new compliance interface

When obligations kick in, the model stops being “just an endpoint.”

It becomes a dependency with versioned evidence.

Think of it like this:

- In 2010, databases forced teams to learn migrations.

- In 2020, microservices forced teams to learn contracts.

- In 2025, GPAI forces teams to learn evidence + governance as part of integration.

Here’s the simplest mental model I’ve found useful:

Evidence artifacts

What the provider can prove about the model: documentation, limitations, testing, policies, summaries.

Operational duties

How the provider runs the model: monitoring, incident response, security posture, change control.

Downstream constraints

What the provider expects you to do: proper use, limits, warnings, human oversight patterns.

Auditability

The ability to reconstruct “what happened” for a given output: logs, versions, configurations.

The rest of this article is: how to build these interfaces into your platform.

What changes for GPAI model providers

If you are a provider, you are no longer shipping “a model.”

You are shipping:

- a model

- plus a packet of evidence

- plus an operating model for risk and incidents

- plus change control that downstream teams can survive

1) You need a “System Card”, not just a model card

A normal model card is a description.

A System Card is a contract:

- intended use vs prohibited use

- known limitations

- safety assumptions (what your mitigations do not cover)

- evaluation scope (what you tested, and what you didn’t)

- integration requirements (logging, retention, input constraints, rate limits, etc.)

If you don’t ship this as a stable artifact:

- enterprises invent their own

- vendors get blamed for downstream misuse

- audits become a fight instead of a review

2) Transparency becomes an API surface

Providers should assume downstream teams will ask for:

- documentation packages tied to model versions

- policies around training data + copyright handling

- summaries of training data characteristics (at the level allowed/required)

- instructions for safe integration (including security notes)

Which means you need artifact versioning as a first-class system:

- model version → artifact bundle version

- artifact bundle version → policy + evaluation run IDs

- evaluation run IDs → stored results + prompts + environments

You have stories.

3) Systemic-risk models turn “safety work” into SRE work

For the class of models treated as higher risk, safety becomes operational:

- continuous evaluation and regression detection

- incident reporting pathways

- red-teaming as a scheduled discipline

- security hardening of serving infrastructure

- monitoring for abuse patterns at scale

That means safety needs the same things SRE needs:

- on-call

- runbooks

- alert hygiene

- postmortems

- “known failure modes” lists

- capacity planning, because denial-of-wallet is also a safety incident

If it’s a set of jobs, dashboards, and runbooks, it might.

What changes for enterprises (even if you’re “just using an API”)

Enterprises tend to make the same mistake:

They treat regulation as a procurement problem.

It is also a runtime problem.

Because the AI Act doesn’t care that your architecture diagram is “clean.”

It cares whether you can:

- control where the model is used

- constrain what it can do

- show what happened

- respond to incidents

- update safely

So the main shift is simple:

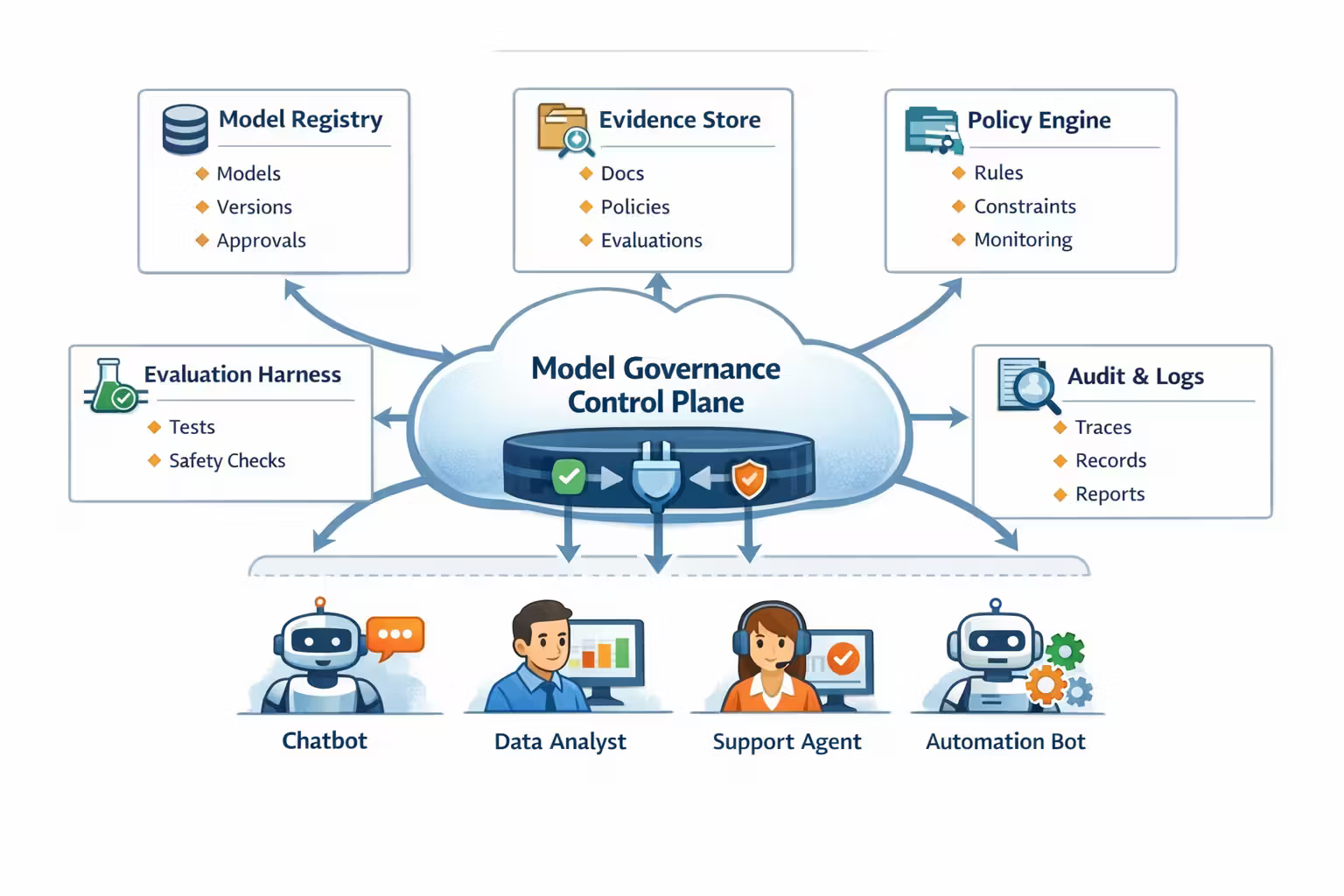

You need a Model Governance Control Plane.

If you don’t build it, you’ll rebuild it repeatedly, badly, in each product team.

The Model Governance Control Plane (MGCP)

A control plane is how platforms avoid chaos.

For GPAI, your MGCP is the place where you answer:

- Which models are approved?

- For which use-cases?

- Under which constraints?

- With which evidence packet?

- With which monitoring?

- With which incident workflow?

The MGCP has five concrete components

Model registry

Inventory of models, versions, vendors, use-cases, risk tags, owners, and approvals.

Evidence store

Versioned storage for provider packets: docs, policies, eval results, and internal sign-offs.

Connector gateway

A single controlled integration surface: auth, quotas, routing, policy checks, logging.

Eval harness in CI

Regression tests for prompts/tools. Blocks model upgrades that break safety and behavior.

Audit log + trace graph

Reconstructable runs: inputs, tool calls, outputs, policies applied, versions used.

Incident workflow

A durable process for “we shipped something bad” that doesn’t rely on Slack archaeology.

Notice what’s missing:

There’s no “compliance team” box here.

Because the platform must make compliance default for engineers.

The connector is now the choke point

In August we talked about connector security:

- least privilege

- injection resistance

- safe toolchains

In September, the conclusion is sharper:

The connector is where you enforce governance.

Why?

- It’s the place all traffic passes.

- It’s where you can apply policy consistently.

- It’s where you can capture logs without begging teams.

So in a regulated world, your connector layer should do four things reliably:

Enforce identity and intent

Who is calling the model, for what purpose, under which product and user session.

Apply policy before generation

Scope tools, block risky actions, enforce data boundaries, require approvals for sensitive flows.

Capture the run

Log prompts, retrieved context hashes, tool calls, outputs, and policy decisions with version IDs.

Control upgrades safely

Route by model version, support canaries, rollbacks, and per-use-case pinning.

This is why “LLM gateway” products exist.

But you can build the core yourself if you treat it like an API gateway with extra semantics.

You have an incident waiting for a regulator to ask: “prove it.”

A practical enterprise playbook: become “GPAI ready” in 6 steps

This is the smallest plan I’ve seen work in real orgs.

It’s boring. That’s why it works.

Step 1 — Build a model inventory you can defend

Minimum fields:

- provider + model name

- version / routing identifier

- owner (a human)

- allowed use-cases

- data sensitivity tags

- risk classification notes

- approval status + date

Step 2 — Define the evidence packet you require from vendors

Ask for a versioned packet containing:

- intended use + limitations

- safety testing summary

- data/copyright posture (at the level available/required)

- integration instructions (rate limits, logging needs, constraints)

- incident contact + reporting expectations Store it in your evidence store and tie it to model versions.

Step 3 — Centralize access through a connector gateway

Do not allow teams to call models directly. Enforce:

- authn/authz

- quotas

- allow-lists for tools

- content controls where appropriate

- logging + trace IDs

Step 4 — Put evaluation in CI for model upgrades

Treat model changes like dependency upgrades:

- define golden prompts + tool scenarios

- define “must not happen” failure tests (data leak, unsafe tool call, policy bypass)

- run it on every upgrade

- block if regressions occur

Step 5 — Ship incident response as a workflow

You need:

- severity definitions

- who is on-call (yes, really)

- a rollback plan (model version pinning)

- a customer comms template

- an internal postmortem process

Step 6 — Create a governance cadence that engineers can live with

Monthly is enough at first:

- review new use-cases

- review incidents and near-misses

- review model upgrade outcomes

- update policies and tests

“Eventually correct” governance: why outbox and sagas matter here

In June we talked about agents as distributed systems.

This month is where that becomes compliance-critical.

A regulated platform needs durable workflows for:

- approvals

- evidence ingestion

- policy changes

- incident handling

- model upgrade rollouts

- audit exports

If these workflows rely on “someone remembering,” you will fail audits and reliability simultaneously.

So the same patterns apply:

- transactional outbox for “we approved model X for use-case Y” events

- sagas for “upgrade model version across 12 services with canaries and rollbacks”

- idempotency keys for every step in the governance pipeline

Treat them like money: durable state machines, retries, and explicit invariants.

A concrete example: an agent that sends emails on a customer’s behalf

Let’s make it real.

You ship a “support agent” that:

- reads a ticket

- drafts an email

- optionally sends it

- updates the CRM

- opens a refund workflow if needed

In 2024, this is mostly “tool use + guardrails.”

In 2025, it also needs:

- proof of which model version generated what

- proof that the agent had the right scope to send email

- proof that the agent didn’t leak other customers’ data into the prompt

- a rollback plan if the model starts producing unsafe drafts

That translates to platform features:

- connector gateway with scoped tokens for email/CRM tools

- trace graph that links ticket ID → prompt hash → tool calls → sent message

- an “approval required” state for refunds above a threshold

- automated eval scenarios that test prompt injection attempts inside ticket text

- an incident runbook (“disable send tool”, “pin to safe model version”, “force human handoff”)

This is what I mean by:

Compliance is a runtime surface.

Common traps (and how teams get hurt)

If you don’t version evidence and logs as you ship, you will never reconstruct the past.

You’ll end up trying to rebuild history from production databases and Slack threads.

This creates inconsistent controls and inconsistent auditability.

Centralize governance at the connector layer and expose it as a platform capability.

Traceability isn’t only for regulators.

It’s how you debug multi-agent workflows and tool misuse.

If you’re building agentic products, you need it anyway.

Prompt filtering is not a governance strategy.

Governance is: least privilege, scoped tools, deterministic policy checks, eval in CI, and audit logs.

The enterprise procurement questions that finally matter

If you take one list into vendor calls, take this one.

Versioning and change control

How do model updates roll out? Can we pin versions? Can we canary? What’s the rollback path?

Evidence packets

What documentation and safety summaries do you provide per model/version? How do we retrieve past packets?

Security posture

How do you prevent abuse, leakage, and compromise in serving? Do you have incident response SLAs?

Auditability support

What logs do you provide? What are retention defaults? Can we export? How do you support investigations?

Notice how none of these are “what’s your benchmark score.”

That’s not because benchmarks don’t matter.

It’s because in 2025, operability beats capability.

Resources

The General-Purpose AI Code of Practice (EU AI Office)

The most “implementation-shaped” artifact for GPAI: concrete measures for transparency, copyright, and (for systemic-risk models) safety/security — plus downloadable templates like the Model Documentation Form.

Commission guidelines for providers of GPAI models

Clarifies key concepts and expectations around GPAI provider obligations. Useful for turning “what the law means” into what your vendor packet and internal model registry must actually contain.

What’s next

September is the month where agents become explicitly regulated platforms.

The next month is where the governance story meets a brutal UX constraint:

voice.

Because voice agents are where latency, caching, reliability, and handoff stop being “nice-to-haves.”

Next article: Voice Agents You Can Operate: reliability, caching, latency, and human handoff

Voice Agents You Can Operate: reliability, caching, latency, and human handoff

Voice turns LLMs into real-time systems. This month is about building voice agents that meet latency budgets, degrade safely, and hand off to humans without losing context—or trust.

Security for Agent Connectors: least privilege, injection resistance, and safe toolchains

In 2025, the riskiest part of “agentic” systems isn’t the model — it’s the connectors. This month is a practical playbook for securing tools: least privilege, prompt-injection resistance, safe side effects, and auditability that holds up under incident response.