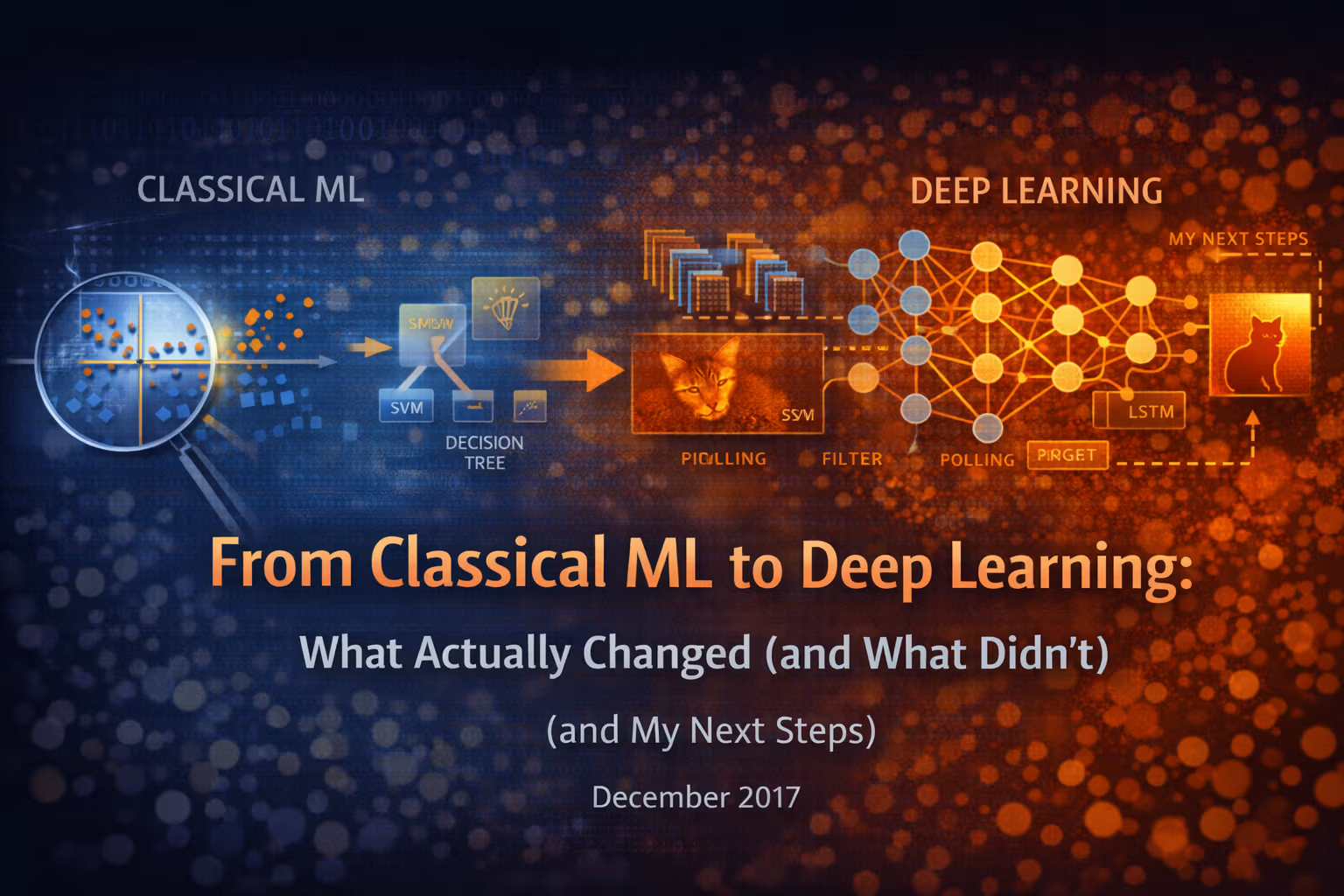

From Classical ML to Deep Learning - What Actually Changed (and What Didn’t) (and My Next Steps)

A year after finishing Andrew Ng’s classical ML course, I’m trying to separate enduring principles from deep learning-specific techniques—and decide where to go next.

Axel Domingues

This closes my 2017 learning sprint.

In 2016, I went through Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning course to remove the magic: implement the algorithms, understand the diagnostics, and learn how to reason about models as systems.

In 2017, I stepped into Neural Networks and Deep Learning—not to chase buzzwords, but to understand why deep nets suddenly started working in practice, and what was genuinely new versus what was the same old ML with bigger compute.

After twelve months of building, breaking, and re-building intuition, I think I can finally answer the question I kept asking all year:

What actually changed… and what didn’t?

- If you want the summary, read “The Short Version” + “The Most Important Lesson”.

- If you want the principles, read “What Stayed the Same”.

- If you want the new deep learning layer, read “What Actually Changed” + “The "Map" I Carry Forward Now”.

The Short Version (if you’ve followed along)

Deep learning felt “new” in 2017 because:

- architectures started encoding domain structure (CNNs for vision, LSTMs for sequences)

- training tricks became first-class engineering (initialization, momentum, gradient clipping, learning rate schedules)

- representation learning replaced feature design (the model learns the features)

But under the hood, the backbone stayed very familiar:

- optimization is still “reduce loss”

- generalization is still “avoid overfitting”

- debugging is still “find the bottleneck”

- good experiments still require discipline

And the classical foundation made the deep learning wave feel understandable instead of mystical.

What Stayed the Same

1) The core loop: define loss → compute gradients → update parameters

Even after CNNs and LSTMs, the workflow was still:

- define a cost that reflects what I want

- compute gradients (backprop is just chain rule applied systematically)

- update parameters (with better optimization methods)

The “new” part wasn’t the loop.

The new part was how hard it became to keep the loop stable at scale.

2) Bias vs variance is still the central tension

I expected deep nets to break this framework.

They didn’t.

If anything, deep learning made it more visible:

- high-capacity models can overfit aggressively

- regularization becomes non-negotiable

- more data doesn’t just help—it changes what architectures become practical

My 2016 instincts still worked:

- if training loss is high: I’m underfitting

- if training is good but validation is bad: I’m overfitting

- if both are noisy: optimization instability or data issues

- “both are noisy” often means optimization instability (learning rate, initialization, gradient issues)

- “underfitting” can be real, but it can also be trainability (the model can’t learn the signal yet)

- “overfitting” can still happen fast because capacity is huge

3) Diagnostics are still the difference between “using” and “engineering”

The biggest continuity from 2016 to 2017 is this:

The model is not the product. The training process is part of the system.

I kept leaning on the same engineering habits:

- sanity check inputs

- monitor loss curves

- inspect gradients when learning stalls

- isolate one change per experiment

- keep baselines alive

What Actually Changed

- Architecture is inductive bias (it encodes assumptions).

- Trainability is a design constraint (not a footnote).

- Representations are learned features (not handcrafted inputs).

- Regularization moved into the whole system (data + procedure + architecture).

- Debugging discipline beats superstition (instrument, baseline, change one thing).

1) Inductive bias moved from “feature engineering” into “architecture”

This was the biggest conceptual shift.

2016 - Bias lived in features

I shaped the input: transforms, kernels, PCA, manual feature design.

2017 - Bias lived in structure

The model structure carried assumptions: locality (CNNs), time (RNNs), stable memory paths (LSTMs).

In 2016, a lot of performance came from features:

- polynomial terms

- normalization choices

- kernels in SVMs

- PCA before a model

In 2017, I watched architectures bake in assumptions:

- CNNs assume locality and translation structure

- pooling assumes some invariance

- RNNs assume sequential dependency

- LSTMs assume memory should have a stable pathway

So “good modeling” became less about manually crafting inputs and more about choosing a structure that matches reality.

Architecture became a form of prior knowledge.

2) Optimization became a first-class design constraint

In 2016, gradient descent felt like a tool.

In 2017, it felt like the boss.

The “deep learning trick bag” wasn’t superficial—it was survival gear:

- ReLU made gradients usable in deeper networks

- proper initialization prevented signal collapse

- momentum made learning practical

- gradient clipping prevented training explosions (especially for RNNs)

- learning rate tuning mattered as much as model choice

The uncomfortable truth I learned:

A model can be theoretically expressive and still be practically untrainable.

And “trainable” is a property you design for.

3) Representation learning replaced manual feature design

CNNs were the turning point for me.

Before CNNs, I thought “features” were something I engineered.

After CNNs, it became obvious that:

- the network is learning filters, edges, textures, shapes

- later layers build abstractions on top of earlier ones

- the representation is part of the learned solution

That shifted how I think about building ML systems:

- I now focus less on “what features should I create?”

- and more on “what structure should I enable the network to discover?”

4) Regularization became architectural and procedural, not just a penalty term

In 2016, regularization was mostly:

- add a penalty

- tune lambda

In 2017, regularization expanded:

- dropout (especially practical in sequence models)

- early stopping

- data augmentation (more relevant for vision)

- architectural constraints (CNN locality, LSTM gates)

- training procedures (learning rate schedules)

So regularization became something I applied in multiple layers of the system, not one knob.

The “Map” I Carry Forward Now

This year made me rewrite my internal checklist.

Instead of thinking “choose algorithm → tune it”, I now think:

Start with the data’s structure

- images → structure in space

- sequences → structure in time

- tabular → structure in relationships and distributions

Choose an architecture that matches that structure

Architecture is not just implementation detail — it’s the inductive bias.

Make training stable before making it clever

If loss doesn’t go down reliably, stop. Fix initialization, learning rates, gradients, batch sizes, clipping.

Regularize in multiple places

- architecture (constraints)

- procedure (early stopping)

- noise injection (dropout)

- data (augmentation where applicable)

Diagnose with discipline

Don’t guess. Instrument. Keep baselines. Change one thing at a time.

My one-page checklist (the version I actually reuse)

- Match architecture to data structure

- Make training stable (loss must go down reliably)

- Regularize across the system (procedure + architecture + data)

- Diagnose with discipline (instrument, baseline, one change at a time)

The Most Important Lesson of 2017

I used to treat “optimization” as a math topic.

Now I treat it as an engineering reality.

Deep learning success is often the result of making optimization possible at scale.

CNNs and LSTMs made this concrete:

- CNNs win because they encode the right bias for images

- LSTMs win because they make gradient flow through time survivable

So the deep learning revolution (as I experienced it) was not magic.

It was a stack of design decisions that finally aligned:

- architecture

- activation functions

- initialization

- optimization strategies

- data scale

The Year in Retrospect (What Each Phase Gave Me)

Foundations (Jan–Mar)

Perceptrons and backprop were “old ideas” that became real only when I implemented and debugged them.

Trainability (Apr–Jun)

ReLU, initialization, momentum: the practical gear that made deep nets stop behaving like fragile math experiments.

Vision (Jul–Aug)

CNNs taught me the power of inductive bias and why representation learning beats manual feature design.

Sequences (Sep–Nov)

RNNs broke my assumptions. LSTMs showed how architecture can solve optimization problems directly.

What’s Next (2018)

I’m ending 2017 with a new kind of excitement.

Deep learning taught me that learning systems can be engineered, not just studied.

And once you start thinking that way, the next question becomes unavoidable:

What happens when the model doesn’t just predict… but acts?

In 2018, I want to shift focus to:

- Reinforcement Learning

- Deep Reinforcement Learning

- and practical implementations using OpenAI Baselines

What pulled me in is the same thing that pulled me into CNNs and LSTMs:

- the idea that architecture + optimization + data can produce behavior that feels like a breakthrough

And yes—the recent results in games (especially Go) make it hard not to be curious.

My goal isn’t to chase headlines.

My goal is the same as it was in 2016:

- build the core ideas from first principles

- develop intuition through debugging

- and understand what breaks when theory meets reality

FAQ

Not in my experience. Deep learning expanded what’s practical for images and sequences, but the classical fundamentals—optimization, regularization, diagnostics—are still the backbone. Deep learning felt understandable precisely because it connected back to those principles.

When the data is small, the problem is tabular/structured, interpretability matters, or you need fast iteration with tight constraints.

Deep learning shines when structure is rich (images, audio, text) and you can afford the training + debugging loop.

How often “the model isn’t learning” was not a data issue or a conceptual issue, but a trainability issue. ReLU, initialization, momentum, clipping—these weren’t optional tricks, they were enabling conditions.

Because it extends everything I learned about optimization and systems into a setting where actions change the data you get back. It feels like the next logical step after spending a year learning how to train deep models reliably.

Rewards, Returns, and Why “Learning” Is an Interface Problem

I’m starting 2018 by shifting from deep learning to reinforcement learning. The first lesson isn’t an algorithm — it’s that the data pipeline is the policy itself.

LSTMs - Engineering Memory into the Network

After vanilla RNNs taught me why gradients collapse through time, LSTMs finally felt like an engineered solution - keep the memory path stable, and control it with gates.