Rewards, Returns, and Why “Learning” Is an Interface Problem

I’m starting 2018 by shifting from deep learning to reinforcement learning. The first lesson isn’t an algorithm — it’s that the data pipeline is the policy itself.

Axel Domingues

I ended 2017 with a strange new kind of confidence.

Not because deep learning became “easy” (it didn’t).

But because I learned a pattern I trust:

learning systems can be engineered — if you treat training as a system, instrument it, and debug it like software.

So in 2018 I’m doing the obvious next thing:

What happens when the model doesn’t just predict… but acts?

I’m not chasing headlines. But I’d be lying if I said the breakthroughs in games (especially Go) aren’t pulling me in. They hint at something I didn’t fully appreciate in 2016 or even early 2017:

behavior can be learned, not just classification.

This first post is not about winning at Atari.

It’s about learning the real starting point of RL:

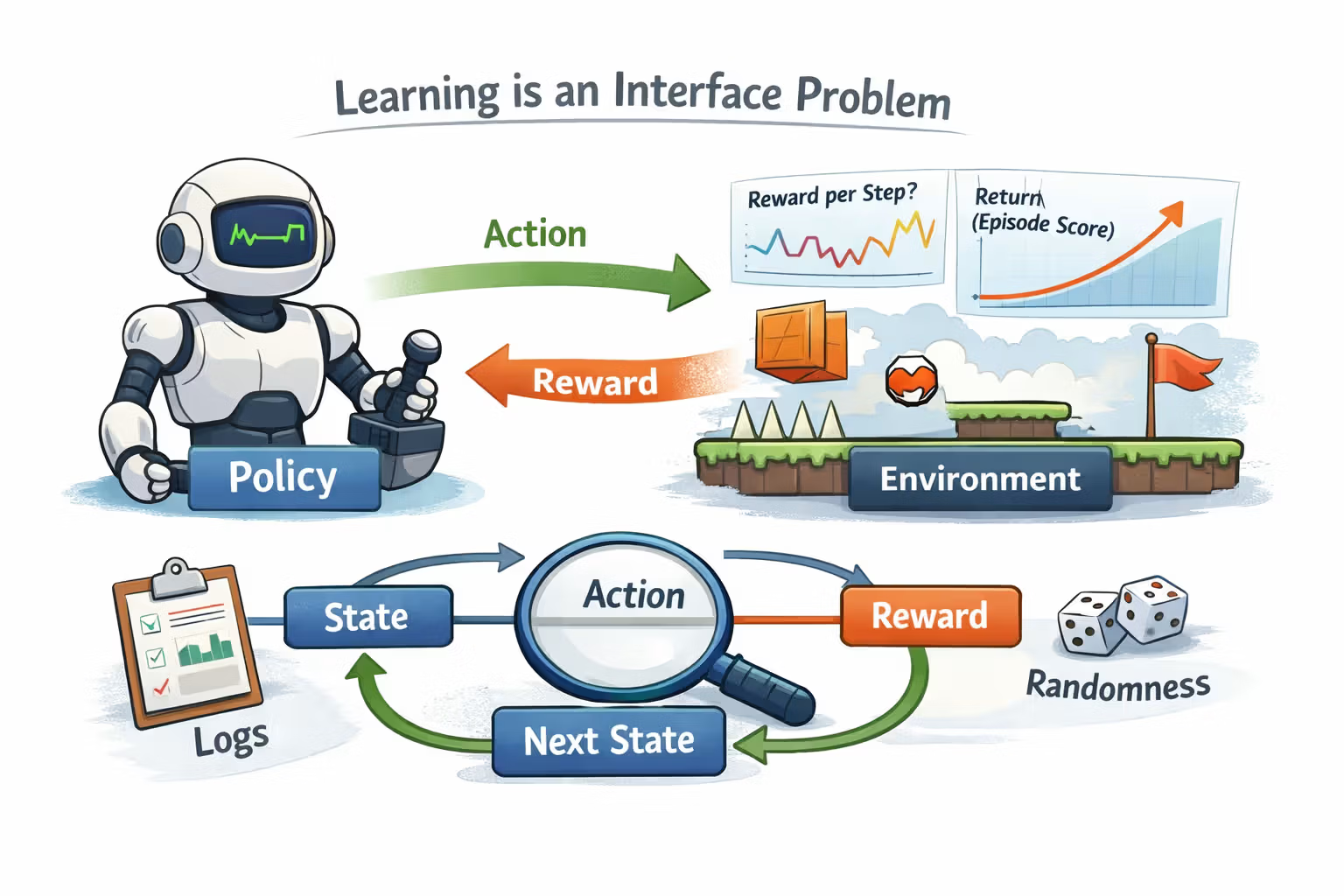

In reinforcement learning, “learning” is mostly an interface problem.

- a clear mental model of the RL loop (agent ↔ environment)

- the practical difference between reward and return

- a starter checklist for debugging RL before you “do algorithms”

- a tiny January plan you can actually execute

The Shift: From Datasets to Loops

Supervised learning mindset

- dataset is fixed

- model predicts

- you minimize a loss

- validation set stays meaningful over time

Reinforcement learning mindset

- “dataset” is generated by acting

- actions change future observations

- policy both learns and collects training data

- data distribution shifts as the policy changes

That one fact changes everything.

It means the first thing to understand is not “the algorithm.”

It’s the interface.

The RL Interface: Agent ↔ Environment

When RL is explained quickly, it sounds simple:

- the agent sees a state

- picks an action

- receives a reward

- moves to the next state

But the part that matters is the loop.

The loop is the product.

- observe something (state)

- choose an action

- environment responds with reward + next observation

- repeat until termination, then reset

Because in RL, your model is not just a function.

It is part of a feedback system.

The pieces (plain English)

- State: what the agent observes right now

- Action: what it chooses to do next

- Reward: a numeric signal the environment emits

- Episode: one run from start to termination

- Policy: the rule the agent uses to choose actions (often stochastic)

- Trajectory: the sequence of states/actions/rewards that happened

- State vs observation: many environments expose an observation that may be incomplete; “state” is often used loosely.

- Policy (stochastic): early RL often relies on randomness for exploration; deterministic policies can get stuck.

- Trajectory vs episode: a trajectory is a sequence; an episode is a trajectory that ends at a termination condition.

And the crucial detail:

The policy changes the distribution of future experience.

That’s why I’m calling it an interface problem.

Reward vs Return: Why “One Number” Isn’t One Thing

At first I kept thinking reward was like a label.

But reward is not a label. It’s a signal.

Sometimes it’s frequent (small reward each step).

Sometimes it’s sparse (nothing… nothing… then a single success signal).

Sometimes it’s noisy. Sometimes it’s exploitable.

And reward isn’t even the full target.

The target you care about is closer to:

- “How good was this whole episode?”

- “Was this sequence of decisions leading somewhere?”

- “Did early decisions set up later success?”

That’s what people mean by return: not “the reward right now,” but the accumulated consequence of behavior over time.

So if you only stare at step rewards, you’ll think nothing is happening.

Reward is what you get.

Return is what you were trying to optimize all along.

Treat “reward per step” as the goal, instead of the episode outcome (or whatever your return actually represents). That misunderstanding leads to bad logging and false conclusions.

Why “Learning Is an Interface Problem”

Here’s the core reason RL feels harder than it “should.”

In supervised learning:

- the model doesn’t influence the dataset

- if training is unstable, it’s usually a local engineering issue (learning rate, initialization, normalization, etc.)

- if the model is wrong, you can still trust the data distribution

In RL:

- the model is inside the data collection mechanism

- as the policy changes, the data changes

- exploration changes what you see

- failures can look like “randomness” unless you instrument aggressively

This is why RL has this reputation of being fragile. It’s not only that the algorithms are complex.

It’s that you’re debugging:

- a policy

- inside a feedback loop

- inside a non-stationary data pipeline

The “dataset” is alive.

If training looks “unstable”, first suspect the interface

- resets and termination boundaries

- reward aggregation (per-step vs per-episode)

- observation preprocessing (shapes, normalization)

- action sampling (stochasticity, clipping)

What “good” instrumentation looks like

- per-episode metrics + moving average

- action distribution

- seed comparisons

- sanity runs with a known dumb policy

My January Goal: Build the Loop Before I Chase Algorithms

I’m deliberately keeping January boring.

I want the smallest possible RL loop that still teaches me something real.

No clever tricks. No tuning heroics.

Just:

- run a simple environment

- run a dumb policy

- log what happens

- confirm I understand the mechanics

Run a random policy on a simple environment

Something like CartPole is perfect because the reward signal is intuitive and episodes are short.

Log the basics before anything “learns”

Episode length, episode reward, and a moving average.

Confirm termination and resets are correct

If I misunderstand episode boundaries, I’ll misinterpret everything later.

Add one tiny sanity check

Track the action distribution: if my agent always takes the same action, I want to notice immediately.

So my January rule is: trust nothing unless you can explain it with logs.You can “improve reward” accidentally with a bug (wrong resets, wrong reward aggregation, leaking state between episodes).

What I Observed (Before Any Learning)

Even with a random policy, I started noticing things that feel uniquely RL:

- Reward curves are deceptive early Randomness can produce “good-looking runs” that mean nothing.

- Episode termination is a first-class concept A bug in termination handling doesn’t just skew metrics — it changes the learning problem.

- Small design choices change the data distribution Even “how I choose actions” changes what states I visit, which changes what I learn from later.

This was the first “interface lesson” showing up in practice:

You don’t learn from the environment.

You learn from the slice of the environment your policy manages to visit.

Engineering Notes: The First Debug Checklist I’m Keeping

This is the checklist I’m keeping at the bottom of my notes for the rest of 2018.

Signals I always log

Episode reward, episode length, moving average, action distribution.

The first “are you lying?” check

Run multiple seeds. If one seed looks amazing, assume luck until proven otherwise.

The first failure mode

Bugs in episode boundaries, resets, or reward aggregation.

If I can’t trust my loop, I can’t trust my learning.

Resources I’m Using

What’s Next

January was about building the loop and respecting the interface.

February is where I want my first real “I can reason about this” win:

Bandits.

Because bandits strip away the complexity of state and time, and force me to face the core RL tension in its simplest form:

exploration vs exploitation.

I want a month where the plots are simple, the behavior is interpretable, and I can stop confusing luck with learning.

FAQ

Not in the way I’m using the words.

Reward is the immediate signal the environment gives you at a step.

Return is the accumulated consequence of decisions over time (the thing you actually care about optimizing).

Because the policy you’re training changes the data you collect.

In supervised learning the dataset is fixed.

In RL the policy is inside a feedback loop, and the “dataset” shifts as the policy changes.

Episode reward and episode length, plus a moving average.

And one that surprised me: action distribution.

If your agent is stuck choosing the same action, you want to see it early.

Because I want a practical reference implementation I can learn from while I build intuition.

I’m treating Baselines as both a toolbox and a teacher: it shows what a production-grade RL training loop needs (logging, wrappers, parallelism, stability tricks).

Bandits - The First Honest RL Problem

Bandits strip RL down to one tension—explore vs exploit—so I can stop confusing luck with learning and start building real intuition.

From Classical ML to Deep Learning - What Actually Changed (and What Didn’t) (and My Next Steps)

A year after finishing Andrew Ng’s classical ML course, I’m trying to separate enduring principles from deep learning-specific techniques—and decide where to go next.