From Logistic Regression to Neurons - Rebuilding Intuition from the Perceptron

After finishing Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning course, I start my deep learning journey by revisiting the perceptron and realizing neural networks begin with ideas I already understand.

Axel Domingues

I finished Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning course at the end of 2016 feeling confident about the fundamentals: linear models, logistic regression, regularization, diagnostics, and how to debug models like an engineer.

So when I decided to shift focus to Neural Networks and Deep Learning in 2017, I expected a sharp break — new math, new mental models, maybe even a bit of magic.

That didn’t happen.

Instead, the first thing I ran into was the perceptron, and my immediate reaction was:

“Wait… I already know this.”

This post is about that moment — and why it mattered more than I expected.

What you’ll learn in this post

How the perceptron connects to logistic regression, and why that makes deep learning feel like a continuation—not a reset.

Best read if you already know

Logistic regression basics, gradients, and why “smooth” functions matter for training.

Mental model to keep

A “neuron” is a building block you can stack, not a totally new kind of magic model.

Why Start With the Perceptron?

The perceptron is often presented as the “origin story” of neural networks. A historical artifact. Something primitive before the real ideas arrive.

But starting here turned out to be important — not because it’s powerful, but because it’s familiar.

The perceptron forced me to ask a very grounding question:

What is actually new about neural networks, compared to the models I already understand?

- Neuron: a small computation unit you can stack into layers.

- Activation: the function applied after the weighted sum (often chosen to be smooth so learning works).

- Bias: the constant term that shifts the decision boundary.

- Layer: a group of neurons operating at the same “depth”.

The First Realization: This Looks Like Logistic Regression

A perceptron takes inputs, multiplies them by weights, sums them up, and passes the result through an activation.

That description already sounded suspiciously close to logistic regression.

Same ingredients:

- weighted sum of features

- a bias term

- a function that turns numbers into decisions

Name the parts you already know

In logistic regression you already do:

- take inputs (features)

- apply weights

- add a bias

- pass it through a function that turns it into a decision/probability

Rename them with “neuron vocabulary”

Same pieces, different framing:

- features → inputs

- parameters → weights

- intercept → bias

- logistic function (or other) → activation

See the “one-neuron” version in plain code

weighted_sum = w1*x1 + w2*x2 + ... + b

output = activation(weighted_sum)

The math feeling isn’t new—what’s new is that this unit becomes something you can stack and compose.

The difference wasn’t what it computes — it was how it’s framed.

It introduced a new unit of composition.

Instead of thinking in terms of “a model”, I was now thinking in terms of neurons as building blocks.

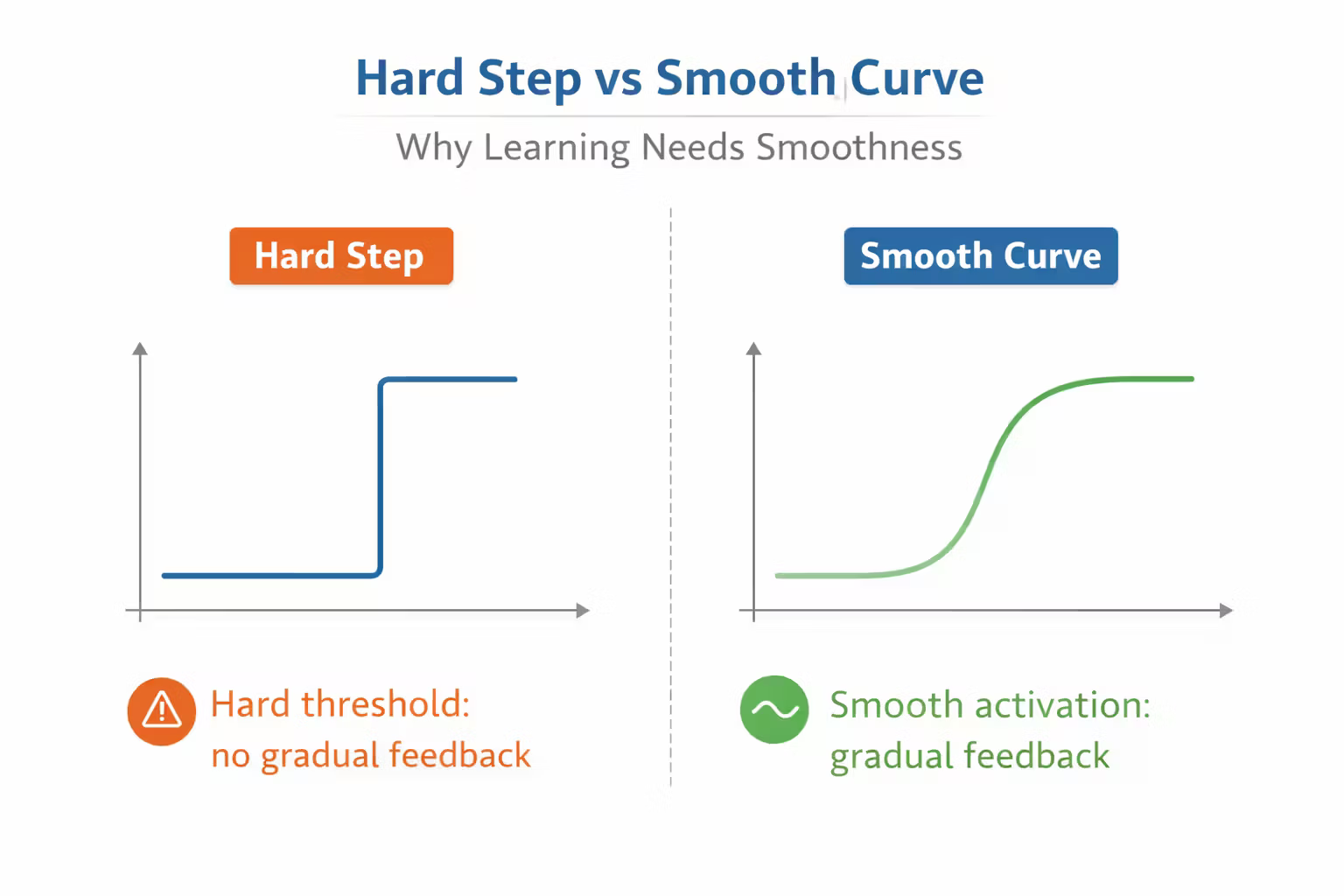

Thresholds vs Smooth Decisions

Historically, the perceptron uses a hard threshold: output 0 or 1 depending on which side of a boundary you land on.

That immediately rang alarm bells.

I already knew from 2016 ML that:

- hard thresholds break gradient-based optimization

- smooth loss surfaces matter if you want learning to work

This is where modern neural networks quietly diverge from the original perceptron idea.

They keep the structure, but replace the hard decision with smooth activations that gradients can flow through.

It was just not trainable at scale.

That distinction — conceptually correct but practically limited — would come up again and again throughout deep learning.

With a hard threshold, tiny changes to weights often produce no change in output until you cross the boundary. That makes “small corrective updates” unreliable—learning becomes unstable or stalls.

A smooth activation changes gradually, so small weight updates produce small output changes. That’s what makes iterative learning feel like steering instead of jumping off cliffs.

When you see training fail later, one of the first questions is: “Did I accidentally create a system where gradients can’t meaningfully flow?”

trainability is often more important than “historical correctness.”

What’s Actually New (And What Isn’t)

This month helped me separate continuity from novelty.

Not new (continuity)

- weighted sums + bias

- gradients and optimization

- regularization concerns

- “debug it like an engineer”

New (novelty)

- stacking units into layers

- learning representations, not just boundaries

- composition as the core superpower

The perceptron didn’t replace my ML intuition — it anchored it.

A Subtle Shift in How I Think About Models

In classical ML, I thought in terms of:

“What hypothesis class am I choosing?”

With neural networks, I started thinking:

“What representations can this architecture build?”

That’s a very different question.

It’s not about drawing a boundary directly — it’s about learning the features that make the boundary simple.

And that idea didn’t fully land yet — but the perceptron was the first crack in the door.

Engineering Notes (What I Paid Attention To)

A few habits from 2016 carried over immediately:

- I treated the perceptron like a system, not a diagram

- I asked how it would behave with noisy data

- I asked how it would fail before asking how it would succeed

I could reason about why they might.

That mindset would become essential very quickly.

What Changed in My Thinking (January Takeaway)

Before this month, I subconsciously thought of neural networks as “a different category of models”.

After revisiting the perceptron, I realized something important:

Neural networks didn’t replace classical machine learning.

They reused it, then scaled it through composition.

That insight made the rest of deep learning feel less intimidating — and more like a continuation of a story I was already part of.

They reuse it, then scale it through composition.

What’s Next

Next, I need to understand the mechanism that makes stacking neurons actually work:

Backpropagation.

I know gradient descent. I know the chain rule.

But applying them together, across layers, is where most explanations get hand-wavy.

That’s what February is for.

Backpropagation Demystified - It’s Just the Chain Rule (But Applied Ruthlessly)

Backprop stopped feeling like magic when I treated it like engineering - track shapes, follow the chain rule, and test gradients like you’d test any critical system.

Exercise 8 + Course Wrap - Anomaly Detection & Recommenders (and My Next Steps)

I wrapped Andrew Ng’s ML course by building anomaly detection and a simple movie recommender—two patterns that show up everywhere in real systems.