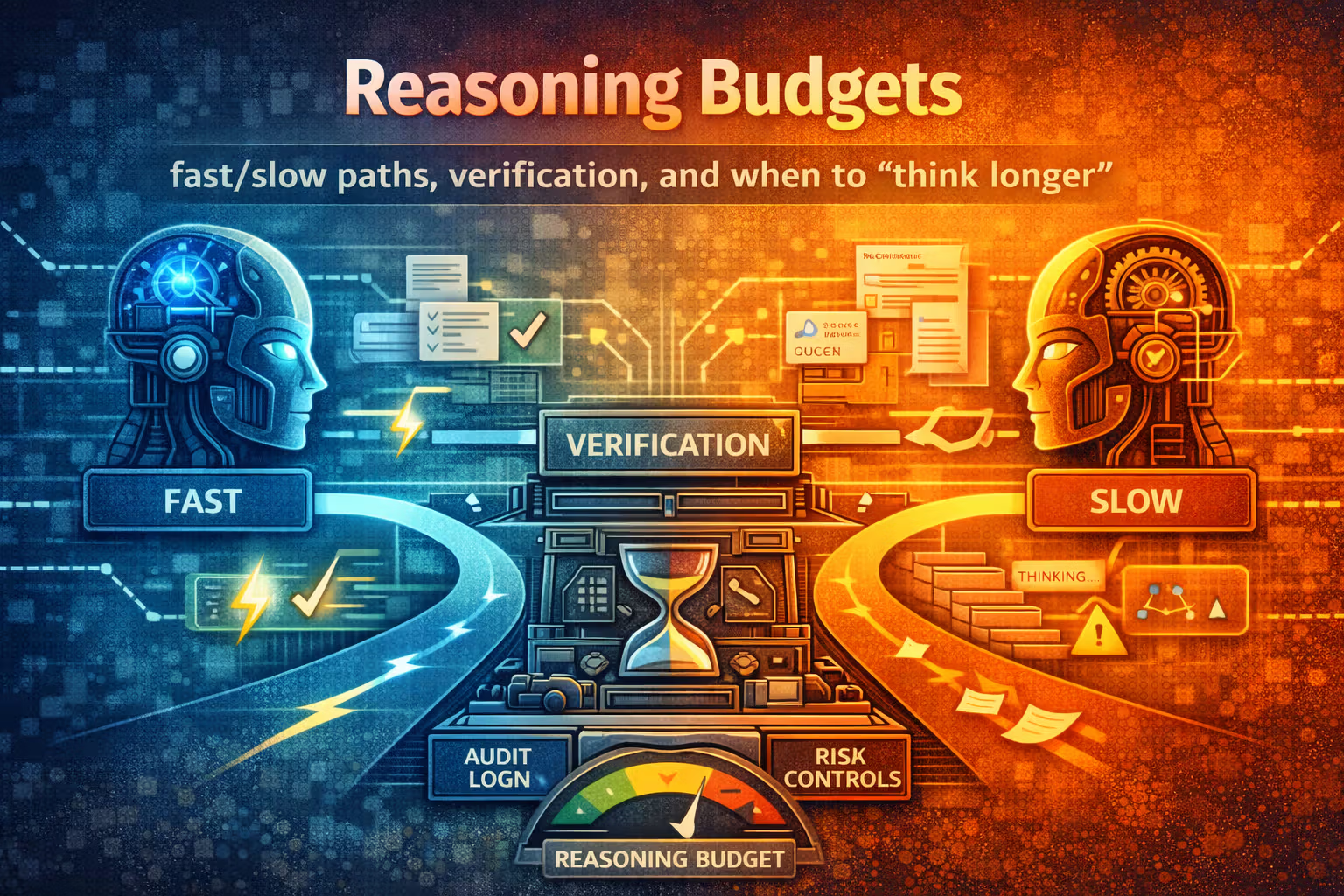

Reasoning Budgets: fast/slow paths, verification, and when to “think longer”

“Think step by step” isn’t an architecture. In production you need budgets, routing, and verifiers so the system knows when to go fast, when to slow down, and when to refuse.

Axel Domingues

“Think longer.”

It’s the most tempting fix in LLM product work — and the most expensive.

Because in production, “thinking longer” isn’t a vibe. It’s a budget decision:

- latency budgets (users leave)

- cost budgets (finance leaves)

- safety budgets (trust leaves)

- and tail budgets (SLOs leave)

October is where I stop treating “reasoning” like a prompt trick and start treating it like a runtime control plane:

route requests into fast/slow paths, verify outputs, and only spend extra compute when it buys measurable reliability.

then “think longer” just produces slower mistakes.If your system can’t:

- say “no”,

- validate tool results,

- and degrade gracefully,

The problem

LLM quality is a function of compute, and compute is a product constraint.

The solution

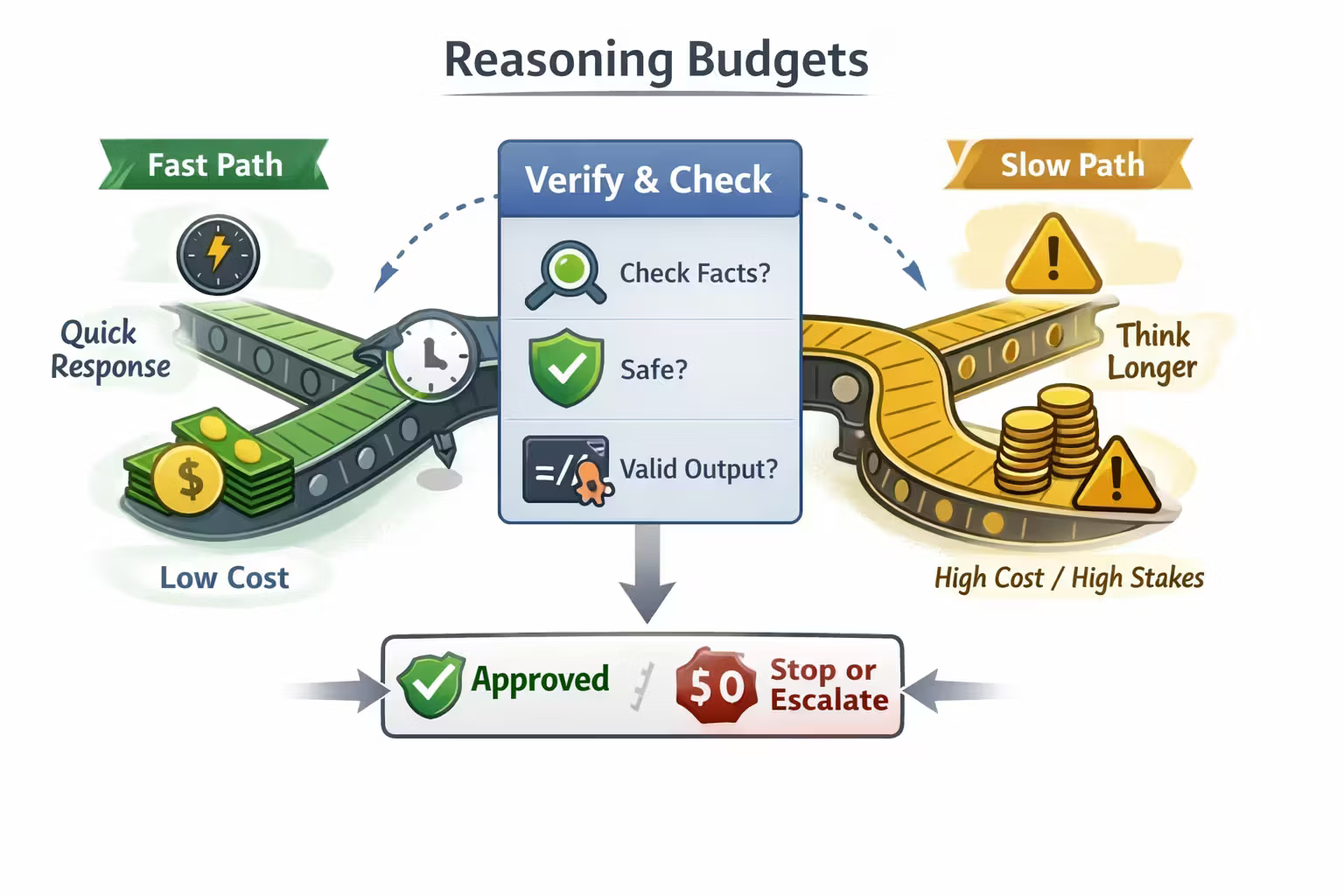

Fast path by default, slow path on demand — with verifiers in between.

The key move

Spend budget on verification, not just generation.

The outcome

Lower cost and fewer incidents by making “thinking” a controlled resource.

“Reasoning budget” is just compute with a purpose

A reasoning budget is the set of limits you impose on a request:

- time (deadline / timeout)

- tokens (max output, max intermediate work)

- tool calls (how many actions and which tools are allowed)

- retries / samples (how many “attempts” you’ll tolerate)

- verification depth (which checks you will run)

This isn’t theoretical. It’s how you turn a stochastic component into a system you can operate.

The moment you allow tools, multi-step plans, or long context, you’re running a workflow engine — and workflows need budgets.

The core pattern: Generate → Verify → Repair → Escalate

If you only have “generate”, you’re not building a product — you’re gambling.

A production-grade assistant needs a loop:

- Generate a candidate

- Verify it (cheap checks first)

- Repair if it failed verification

- Escalate to a slower/more expensive mode if it’s still failing

- Fallback / refuse if you’re out of budget or outside capability

Even simple checks (schema, citations, tool output validation) remove a shocking amount of failure.

Fast path vs slow path

A good default architecture is:

- Fast path: low-risk requests, tight budget, minimal tools, minimal retries

- Slow path: ambiguous or high-stakes requests, larger budget, stronger verification, careful tool use

This isn’t “two models”. It’s two operating modes.

Fast path (what it’s for)

- quick Q&A

- summarization and rewriting

- low-impact content generation

- UI helper interactions (autocomplete, drafts)

Slow path (what it’s for)

- anything that triggers tool use (payments, emails, database writes)

- regulatory / safety-critical domains (health, legal, compliance)

- multi-step workflows that can compound errors

- “I’m not sure” situations where the cost of being wrong is higher than the cost of waiting

It’s more constraints plus more checking.

The router: deciding when to “think longer”

The router is a policy. Make it explicit.

In practice, you score a request with a few signals:

Impact

Does an error create real harm (money, safety, reputation)?

Uncertainty

Is the model likely to be wrong without extra grounding or checks?

Complexity

Does it require multi-step reasoning, long context, or tool chaining?

Attack surface

Does it touch tools, credentials, code execution, or user data?

A simple routing rule can look like this:

- impact high → slow path

- tools involved → slow path (or sandbox-only)

- uncertainty high → run verification; escalate if it fails

- attack surface high → restrict tools, require allowlists, require human approval

A practical heuristic: “risk tiers”

I like three tiers because teams can actually operationalize them:

- Tier 0 (Safe): no tools, no sensitive data, low impact

- Tier 1 (Caution): user-visible output with reputational risk (support answers, summaries)

- Tier 2 (Critical): anything that changes state (sends email, writes DB, executes code, triggers payments)

Then you define budgets per tier.

Executives understand tiers. Engineers can map tiers to controls.Call it “Tier 2 execution policy”.

Verification is where budgets turn into reliability

Spending budget on “more tokens” is a weak strategy.

Spending budget on checks is a strong strategy.

Here are the verifiers that consistently pay off.

If the output must drive downstream automation, force it into a contract:

- JSON schema validation

- strict enums for actions

- bounded string lengths

- required fields

- “no extra properties” in critical payloads

If validation fails, you repair, not “hope”.

Tools are not truth. They are inputs.

Validate:

- tool response types and ranges

- signed/authorized identities

- freshness (timestamps)

- “did the tool actually do what we asked?”

A classic failure mode is the model “summarizing” tool output incorrectly. So: keep tool output as structured data and render from it deterministically.

If you’re using RAG:

- require citations for factual claims

- verify citations exist in retrieved chunks

- detect contradictions between top documents

- rerank and retry retrieval if results disagree

RAG is not grounding unless you verify the grounding happened.

Some correctness is not “model work”.

If a policy says:

- max discount is 15%

- shipping can’t be scheduled in the past

- PII must not appear in logs

Then enforce it with code. This is how you define truth boundaries.

A second pass can help, but treat it as expensive.

Use it when:

- the first answer fails checks,

- the user asks for high confidence,

- or the domain is Tier 2.

Design it as: critique → produce a minimal diff → re-verify.

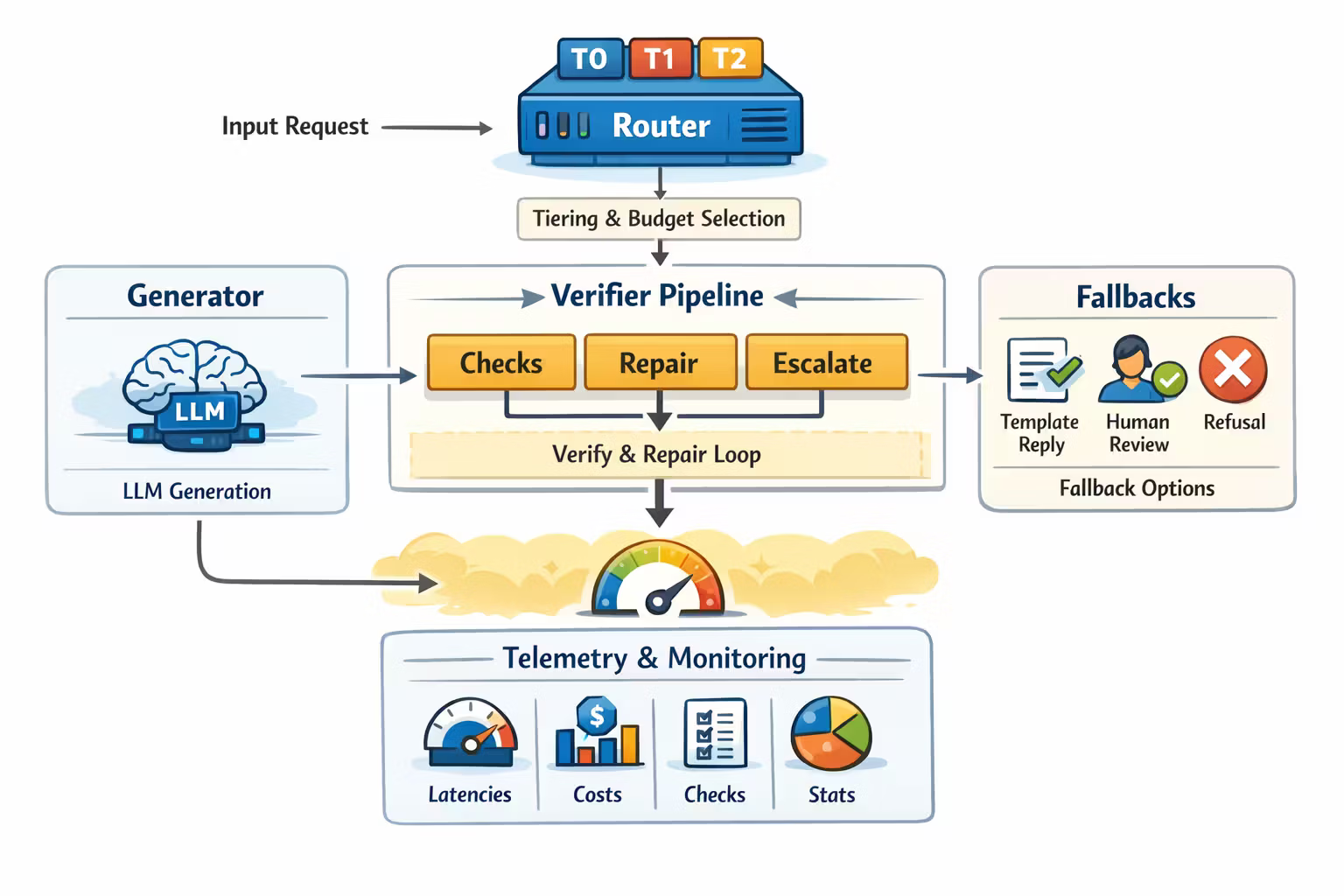

A minimal architecture that scales

This is the smallest set of components I’ve seen work repeatedly:

- Router (tiering + budget selection)

- Generator (LLM call(s))

- Verifier pipeline (cheap → expensive)

- Repair loop (structured retries)

- Fallbacks (template responses, “human required”, refusal)

- Telemetry (budgets burned, checks passed/failed)

If you can’t answer “what percent of slow-path escalations actually improved outcomes?”

then you’re spending money blindly.

Budgeting tactics that actually work

1) Put a deadline on the whole request

Every request needs a deadline. Even internal ones.

- The user might wait 2 seconds for autocomplete.

- They might wait 10–20 seconds for a complex workflow.

- They will not wait forever because your agent is “thinking deeply”.

So: define a deadline and make the system degrade gracefully when it hits it.

2) Run cheap checks first, always

Order verifiers by cost:

- schema checks (cheap)

- rule checks (cheap)

- citation existence checks (cheap-ish)

- retrieval retries (medium)

- critique / resample (expensive)

3) Use stop conditions aggressively

Stop when:

- verification passes

- budget is burned

- the model is looping (same failure twice)

- the request is out of policy

This turns an agent from “infinite wanderer” into a bounded system.

4) Cache verified results (with fingerprints)

Caching is safe when you include a fingerprint:

- prompt template version

- tool version

- model version (or capability tier)

- retrieval corpus version

- user policy/tier

Cache only when the output is:

- deterministic enough,

- verified,

- and not privacy-sensitive.

Implementation sketch (how to wire this in practice)

Below is a deliberately boring sketch. Boring is good.

It shows how to structure the runtime so budgets are enforced, not “suggested”.

type Tier = "T0" | "T1" | "T2";

type Budget = {

deadlineMs: number;

maxTokens: number;

maxToolCalls: number;

maxRepairs: number;

allowTools: string[]; // allowlist

verifierLevel: "basic" | "standard" | "strict";

};

type Candidate = {

text: string;

toolCalls?: Array<{ name: string; args: unknown }>;

citations?: Array<{ id: string; span: [number, number] }>;

};

type Verdict =

| { ok: true; normalized: unknown }

| { ok: false; reason: string; repairHint?: string };

async function handleRequest(input: { userText: string }) {

const { tier, budget } = route(input);

const start = Date.now();

let attempts = 0;

while (attempts <= budget.maxRepairs) {

const timeLeft = budget.deadlineMs - (Date.now() - start);

if (timeLeft <= 0) return fallback("timeout", tier);

const candidate: Candidate = await generate(input, { tier, budget, timeLeft });

const verdict: Verdict = await verify(candidate, { tier, budget, timeLeft });

if (verdict.ok) return render(verdict.normalized);

attempts += 1;

// If we failed for a repeatable reason, repair with guidance.

input = { ...input, userText: input.userText + "\n\nRepair: " + (verdict.repairHint ?? verdict.reason) };

// Optional escalation: only when it's worth it.

if (shouldEscalate(verdict, tier) && tier !== "T2") {

return handleRequestEscalated(input);

}

}

return fallback("verification_failed", tier);

}

The important detail isn’t the code.

It’s the discipline:

- budgets are parameters, not comments

- verification is a first-class stage

- retries are bounded

- escalation is explicit

- fallback exists

What to log so you can improve budgets (not argue about them)

If your team can’t see the system, they will debate it endlessly.

Here’s the minimum telemetry that turns this into engineering:

Budget burn

Tokens, time, tool calls, retries per request + per tier.

Verification stats

Which checks failed, how often, and whether repairs succeed.

Escalation ROI

Did slow-path escalation improve outcomes (quality, fewer incidents)?

Tail latency

p95/p99 latency per tier, with breakdown by stage.

If you can’t define what “verified” means, you can’t optimize.

Common failure modes (and how budgets prevent them)

Cause: no stop conditions, no bounded retries.

Fix:

- max repairs

- duplicate-failure detection

- hard deadline

Cause: downstream automation consumes free-form text.

Fix:

- schema-first outputs

- deterministic rendering

- strict validation

Cause: tools are too powerful and too implicit.

Fix:

- allowlisted tools per tier

- argument validation

- human approval for Tier 2 actions

- sandbox for anything executable

Cause: treating every request as high-stakes.

Fix:

- explicit tiering

- fast path by default

- verify-and-escalate only on failure

Resources

The Tail at Scale (Dean & Barroso, 2013)

The canonical read on tail latency and why p95/p99 dominates UX and SLOs — the “tail budget” intuition your fast/slow paths are built on.

Self-Consistency for Chain-of-Thought (Wang et al., 2022)

A concrete “spend budget on reliability” technique: sample multiple reasoning paths, then pick the most consistent answer (useful framing for resamples / retries).

FAQ

Better models help, but they don’t remove the architectural problem:

- you still need budgets (latency/cost)

- you still need verification (tools can still be wrong)

- you still need fallbacks (some requests are out of scope)

Upgrading the model without upgrading the runtime is how teams get surprised in production.

Start with three tiers and pick budgets that match the user’s patience:

- Tier 0: ultra-fast, minimal tools, minimal retries

- Tier 1: moderate, verification on key outputs

- Tier 2: slower allowed, strict verification, human approvals

Then iterate based on telemetry: which verifiers catch real issues, and which escalations actually improve outcomes.

Refuse when:

- the request is out of policy

- verification repeatedly fails

- the action is unsafe without human approval

- the system can’t meet the user’s deadline reliably

Refusal is not failure — it’s a safety boundary.

What’s Next

Once you have budgets and verification, you can start doing something harder:

real-time interaction.

In November, the topic is the next constraint that changes everything:

Real-Time Agents: streaming, barge-in, and session state that doesn’t collapse

Because the moment you stream responses and accept interruptions, your “reasoning budget” becomes a session budget — and the runtime has to stay stable while the user is actively steering it.

Real-Time Agents: streaming, barge-in, and session state that doesn’t collapse

Real-time agents aren’t “LLMs with voice.” They’re distributed systems with hard latency budgets. This month is about streaming UX, safe interruption (barge-in), and session state you can actually operate.

Regulation as Architecture: Turning the EU AI Act into Controls and Evidence

The EU AI Act isn’t a PDF you “comply with” — it’s a set of control objectives you design into your product: evaluation, documentation, monitoring, and provable safety boundaries.