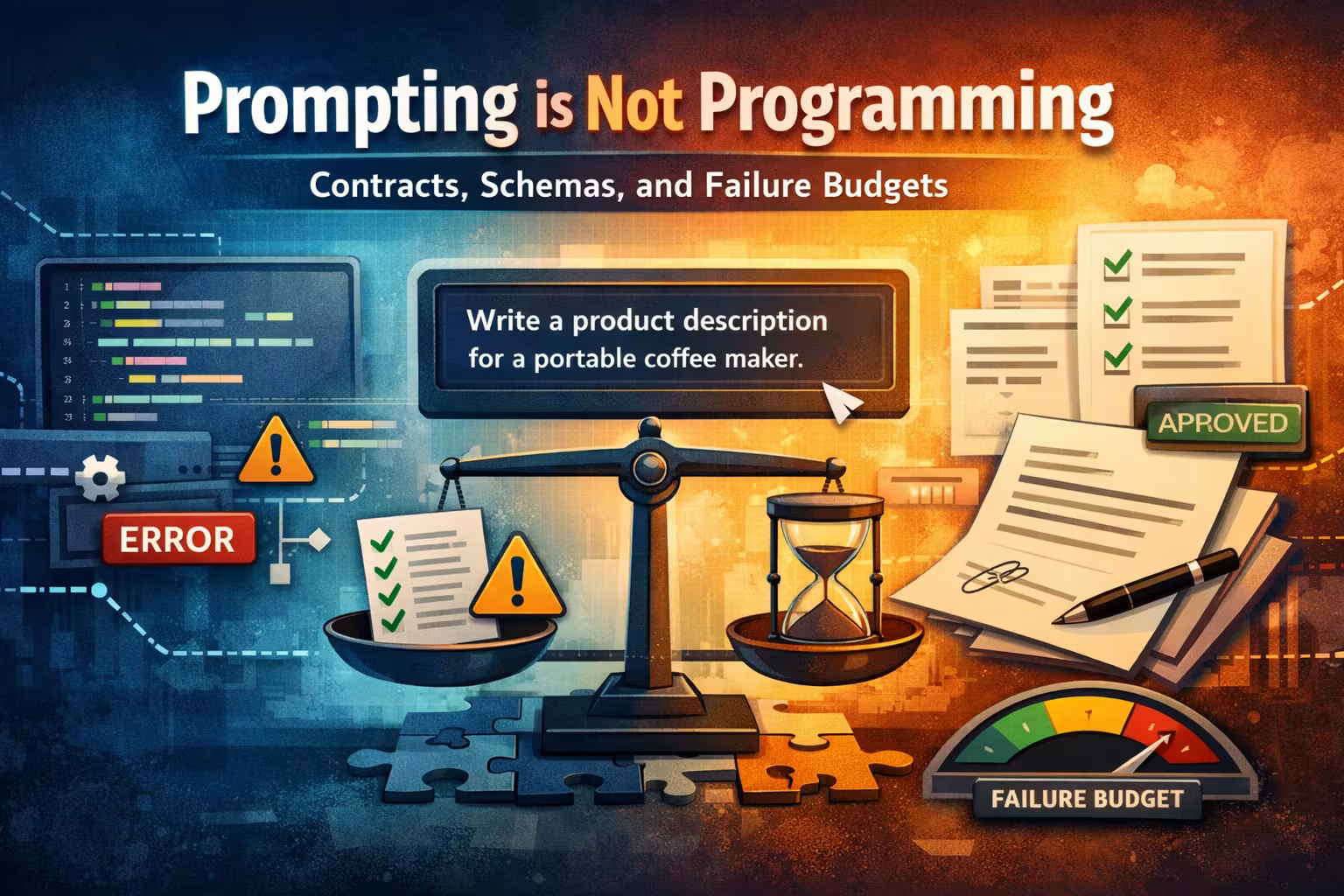

Prompting is Not Programming: Contracts, Schemas, and Failure Budgets

Prompting feels like coding until it fails like statistics. This month I start treating LLMs as probabilistic components: define contracts, enforce schemas, and design failure budgets so your system survives outputs that are “plausible” but wrong.

Axel Domingues

In 2023, we learned the hard truth:

LLMs don’t “return answers.” They return samples.

In 2024, the work changes.

More system design.

Because the moment you ship an LLM feature to real users, you discover a new category of bug:

Nothing crashed.

The output was just… wrong.

That’s not a coding bug.

That’s a contract bug.

And if you treat prompting like programming, you’ll keep trying to fix a probabilistic system with deterministic habits.

So for the first article of the 2024 series (From LLM features to agents you can operate), I’m going to establish the posture that makes LLM work shippable:

- define contracts (what is allowed, what is forbidden)

- enforce schemas (what shape is acceptable)

- design failure budgets (how wrong can it be before we change the system)

Because reliability is not a model property.

Reliability is designed.

The mental shift

Prompts are not programs.

They’re inputs to a probabilistic component.

The engineering shift

Move reliability out of the prompt and into a boundary layer.

The practical output

A reusable LLM Boundary Layer you can apply to every feature.

The success metric

The feature degrades safely under failure and improves via measurement.

The Mistake: Treating a Prompt Like Code

When you write code, you assume:

- the same input produces the same output

- if it fails, it fails predictably

- correctness is (mostly) binary

When you prompt a model, none of those assumptions are safe:

- the same input can yield multiple plausible outputs

- failures can be soft (confident but incorrect)

- “correct” often depends on context, not syntax

So the right comparison isn’t “prompting is like coding.”

Prompting is closer to:

- calling an external service you don’t control

- parsing untrusted input

- running a heuristic classifier

- integrating a human collaborator (who sometimes misunderstands you)

Which means you need what we always need for untrusted systems:

boundaries.

The prompt is not the system.

The prompt is one part of the system.

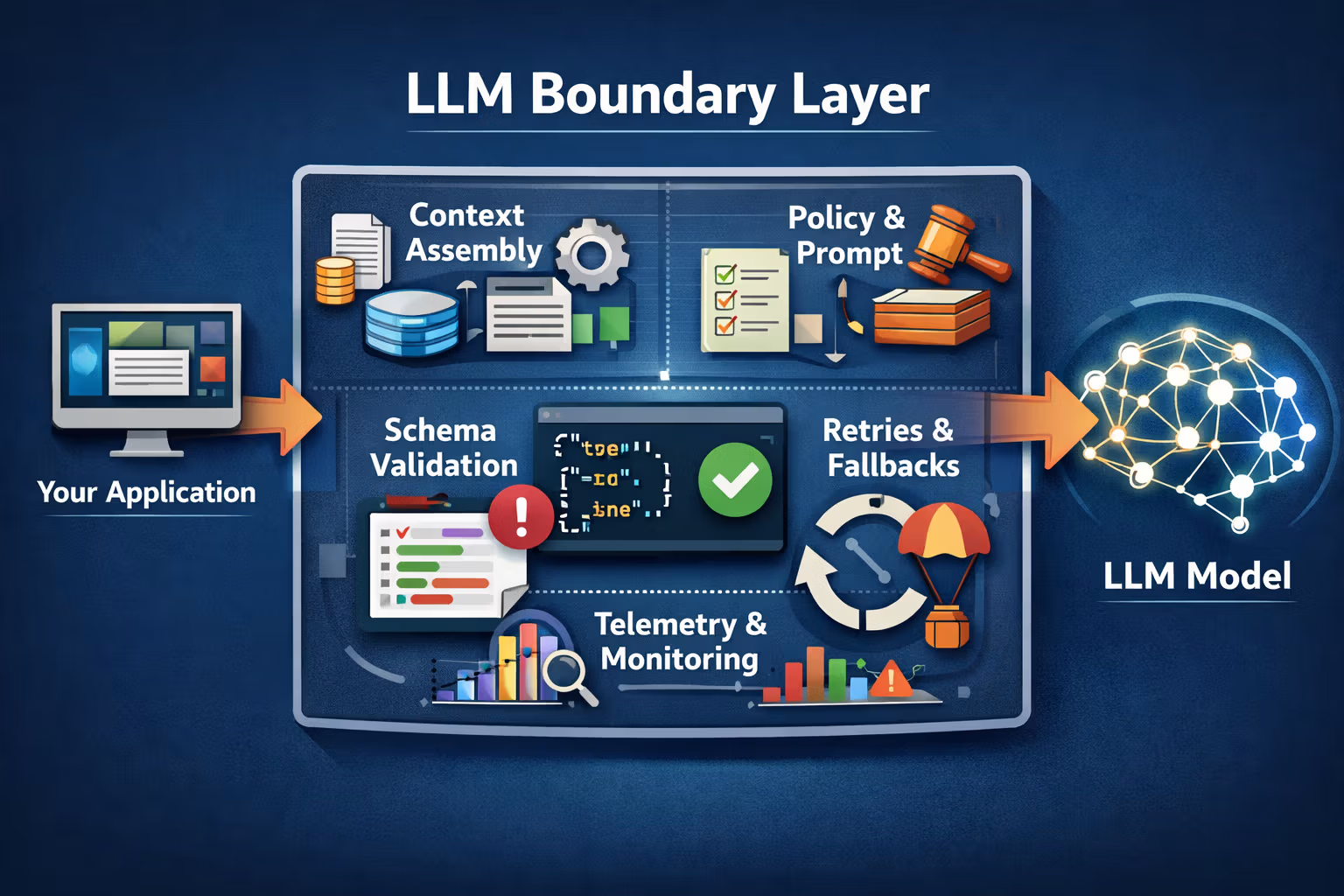

The LLM Boundary Layer

If you’re building LLM features professionally, you want a dedicated layer that sits between your product and the model.

Not because it’s fashionable.

Because you need a place where reliability actually lives.

Here’s the boundary I recommend for almost every production integration:

At minimum, the boundary layer owns:

- Input contract: what the model is allowed to see and do

- Output contract: what the system will accept

- Schema enforcement: parse + validate + repair

- Failure policy: retry strategy, fallback strategy, human-in-the-loop

- Telemetry: logs, metrics, traces, evaluation hooks

The point is simple:

Your product should talk to a stable interface.

The boundary layer should deal with model weirdness.

Part 1 — Contracts: Define “What Must Never Be Wrong”

A contract is not a prompt. A contract is an agreement between your system and the model about what is acceptable.

Think of it like any other architecture boundary:

- APIs have contracts

- DB schemas enforce invariants

- payment systems have non-negotiables

LLM features need the same adult supervision.

Start with truth boundaries (invariants)

Before you write a single prompt, answer two questions:

- What must never be wrong?

- What can be “probably right” and still be acceptable?

Examples:

- In a medical context: never fabricate dosage instructions

- In a finance context: never claim a transaction completed unless confirmed

- In a support context: never reveal private customer data

- In a compliance context: never invent policy/legal statements

That’s how hallucinations become incidents.

Write the contract as an interface

A good LLM contract is explicit, bounded, and testable.

Here’s a simple contract template I use:

- Task: what the model is being asked to do

- Inputs: what the model receives (and what it must not receive)

- Allowed actions: tools it may call (and with what scopes)

- Forbidden actions: anything unsafe / outside policy

- Output shape: required fields and their constraints

- Grounding: what sources it can cite or must use

- Escalation: what to do when uncertain

Contract question

What must never be wrong?

Contract question

Where is “probably right” acceptable?

Contract types you’ll use repeatedly

Most LLM work falls into a few contract families:

Goal: extract fields, not “answer questions.”

Reliability lever: strict schema + validation + repair.

Failure mode: missing fields, wrong types, invented values.

Goal: pick from a small controlled set.

Reliability lever: constrained outputs + confidence rules + fallback to “unknown.”

Failure mode: overconfident misroutes.

Goal: help a human write faster.

Reliability lever: make it obviously a draft + include citations/notes.

Failure mode: users treat it as authoritative.

Goal: take actions safely.

Reliability lever: tool scopes, step limits, sandboxing, audit logs.

Failure mode: doing the wrong thing “helpfully.”

The key: don’t use a drafting contract for an extraction problem. That’s how you end up parsing prose like it’s data.

Part 2 — Schemas: Make “Output Shape” a First-Class Constraint

If contracts are “what must be true,” schemas are “what must be parseable.”

Schemas are how you turn “the model said a thing” into “the system accepted a thing.”

Why schemas matter

Without a schema, you’re doing this:

- ask for something

- get prose back

- guess what it means

- hope it’s correct

- ship it

With a schema, you can do this:

- ask for a structured object

- validate it

- reject or repair it

- measure failures

That’s real engineering.

It makes the system reject nonsense early and reliably.

The minimum viable schema approach

You don’t need a giant framework to start. You need four steps:

- Constrain the output to JSON (or a typed object)

- Validate against a schema (types + required fields)

- Repair with a bounded retry loop

- Fallback if still invalid

Here’s a simple JSON Schema example for an “intent router”:

{

"type": "object",

"required": ["intent", "confidence", "needs_human"],

"properties": {

"intent": {

"type": "string",

"enum": ["billing", "technical", "account", "sales", "other"]

},

"confidence": { "type": "number", "minimum": 0, "maximum": 1 },

"needs_human": { "type": "boolean" },

"notes": { "type": "string" }

},

"additionalProperties": false

}

And here’s the logic you want around it (pseudo-code, language-agnostic):

for attempt in 1..max_attempts:

raw = llm(prompt, context)

json = try_parse_json(raw)

if not json:

prompt = repair_prompt(raw, "Output was not valid JSON.")

continue

if validate(json, schema):

if json.confidence < 0.6: return fallback("low_confidence")

if json.needs_human: return escalate(json)

return accept(json)

prompt = repair_prompt(raw, "JSON failed schema validation.")

return fallback("schema_failure")

That loop is the difference between a demo and a system.

Unbounded retries are how “LLM reliability” becomes “infinite latency and infinite cost.”

Common schema pitfalls (and fixes)

Fix: set additionalProperties: false (or the equivalent) and reject unknown fields.

Fix: explicit “required” set + repair prompt that lists missing fields.

Fix: allow null / “unknown” for specific fields, then enforce escalation rules.

Fix: strict validation + repair prompt + (optionally) a small deterministic coercion step you control.

Fix: strip fences deterministically, then validate.

The main rule:

The model can generate.

Only your boundary layer can accept.

Part 3 — Failure Budgets: Stop Arguing With the Model, Start Operating the System

Here’s where most teams get stuck:

They keep rewriting prompts to reduce failure.

That helps… until it doesn’t.

Because you can’t prompt your way out of probabilistic behavior. You can only budget it.

A failure budget is an operational idea:

- you decide how much failure is acceptable for a feature

- you measure actual failure

- when you exceed the budget, you change the system

This is the same thinking that made SRE work: availability isn’t a wish — it’s a budget.

What “failure” means for an LLM feature

LLM failures are not just “500 errors.” Most are semantic.

Define failure categories that match reality:

Invalid output

Not parseable / schema-invalid / missing required fields.

Wrong-but-plausible

Semantically incorrect while sounding confident.

Unsafe output

Policy violations, privacy leaks, jailbreak behavior.

Cost/latency blow-up

Retries, long prompts, token spikes, tool loops.

Now you can put numbers on them.

Example failure budgets (illustrative):

- invalid output: < 0.5% of requests

- unsafe output: 0 tolerated (block, escalate, hard fail)

- wrong-but-plausible: < 2% (plus a verification gate on high-risk flows)

- latency budget: p95 < 2s for interactive endpoints

- cost budget: < $X / 1k requests

The exact numbers depend on your product. The important part is: you choose them and you track them.

Failure budgets force better design choices

If wrong-but-plausible errors are too high, your options are not “try a better adjective.”

Your options are architectural:

- narrow the contract (smaller output space)

- add grounding (retrieve authoritative sources)

- add verification (two-pass check, rule-based checks, human review)

- change the UX (make uncertainty visible)

- restrict actions (tools + scopes)

- route to a stronger model for high-risk cases

- degrade gracefully (fallback to deterministic rules)

This is how the system improves over time without turning into prompt folklore.

A failure budget is an operating model.

The Practical Pattern: “Accept / Repair / Escalate / Fallback”

You want every LLM feature to have an explicit outcome policy. Here’s the one I use most often:

- Accept if schema-valid and within risk thresholds

- Repair if formatting/validation failed (bounded retries)

- Escalate if uncertainty is high or stakes are high

- Fallback if the system can’t safely proceed

That policy gives you predictability even when the model is unpredictable.

Escalation is not a defeat

Escalation is a product feature.

It’s the system saying:

“I am not confident enough to be autonomous.”

That is what “operable agents” will mean in 2024: bounded autonomy with explicit handoffs.

How to Build Your Boundary Layer in One Week

If you’re starting from scratch, don’t boil the ocean. Build the minimal boundary that makes the feature safe.

Define the contract in one page

Write:

- task, allowed actions, forbidden actions

- what must never be wrong

- output shape and escalation rules

Implement schema validation

Pick one:

- JSON schema validation

- typed validator (Pydantic / Zod / io-ts)

- function-call style structured output (if your stack supports it)

Add a bounded repair loop

- max 2–3 attempts

- log failures

- count “repair success” as a metric

Add a fallback path

- deterministic fallback for low-risk tasks

- human-in-the-loop for high-risk tasks

- clear user messaging

Add telemetry hooks

Track:

- schema failure rate

- repair rate

- escalation rate

- token usage and latency

- a small sample of red-team tests in CI

That’s enough to ship responsibly. Everything else is iteration.

What to Measure (So You Don’t Hallucinate Reliability)

In early LLM projects, teams often use “it seems fine” as the main metric.

That’s a trap.

Your boundary layer should expose a small dashboard of truth:

- Schema failure rate (how often output is invalid)

- Repair success rate (how often retries fix it)

- Escalation rate (how often you hand off)

- User-visible failure rate (how often the feature fails in UX)

- Cost per request (tokens + retries + tools)

- Latency p95 (and where time is spent)

- Top error modes (clustered: parse, missing fields, wrong intent, etc.)

It’s the same loop you used in distributed systems: observe, constrain, stabilize.

A Quick Example: Turning “Summarize This Email” Into a Safe Feature

Let’s make this concrete.

The naive prompt:

- “Summarize this email.”

The engineered version:

Contract

- output must be a structured summary

- must not include private secrets beyond what the user provided

- must include “unknown” where details are not present

- must flag if legal/financial claims are detected

Schema

summary_bullets(array, 3–7)action_items(array)tone(enum)sensitive_flags(array of enums)

Failure policy

- if schema fails: repair up to 2 times

- if

sensitive_flagscontains high-risk: escalate (user confirmation) - if still invalid: fallback to “extract first 3 sentences” deterministic approach

That’s the difference between “a cool demo” and “a feature I can operate.”

FAQ

If the output doesn’t matter, you can keep it casual.

But the moment:

- you store outputs in a DB,

- trigger downstream actions,

- or users make decisions from the output…

you need contracts, schemas, and failure budgets.

Start small — but start with a boundary.

It reduces a class of failures:

- unparseable output

- missing fields

- invented structure

It does not magically make facts correct.

For factuality, you need grounding + verification, which we’ll build throughout 2024.

Stop searching for “the perfect prompt.”

Instead:

- define the contract,

- enforce the schema,

- and operate the failure budget like an SLO.

This turns LLM work from art into engineering.

Shipping unstructured prose into downstream logic.

If code depends on model output, the output must be structured, validated, and versioned.

What’s Next

This month was the foundation:

- prompts are not programs

- reliability lives in boundaries

- schemas turn output into something the system can safely accept

- failure budgets turn “LLM weirdness” into an operable reality

Next month we hit the 2024 shift that breaks a lot of teams’ intuition:

Long context isn’t memory: when to stuff, when to retrieve

Because the moment you get bigger context windows, it becomes tempting to “just paste everything.”

And that’s when cost, latency, and retrieval strategy become architecture again.

Long Context Isn’t Memory: When to Stuff, When to Retrieve

Bigger context windows tempt teams to paste everything. But long context is just a larger input buffer — not memory, not grounding, and not a plan. This month: how to budget context, decide “stuff vs retrieve,” and build a context assembler that stays fast, cheap, and safe.

Midjourney and the Product Loop: Why Some Generators Feel Magical

Diffusion models made image generation possible. Midjourney made it feel addictive. The difference wasn’t just the model — it was the product loop: fast iteration, visible search, and UI as a steering system for probability.