Long Context Isn’t Memory: When to Stuff, When to Retrieve

Bigger context windows tempt teams to paste everything. But long context is just a larger input buffer — not memory, not grounding, and not a plan. This month: how to budget context, decide “stuff vs retrieve,” and build a context assembler that stays fast, cheap, and safe.

Axel Domingues

January was about contracts:

- define what must never be wrong

- force structure with schemas

- operate failures with budgets

February is about the temptation that breaks those disciplines:

“We have a bigger context window now.

Why not just paste everything?”

Because long context isn’t memory.

It’s not even understanding.

It’s just a larger place to put tokens before you press “run.”

And if you treat it like a free memory upgrade, you’ll ship systems that are:

- expensive

- slow

- easy to jailbreak via document injection

- and surprisingly unreliable (because attention is not a perfect search engine)

So this month is a practical guide to a simple question:

When should you stuff context, and when should you retrieve?

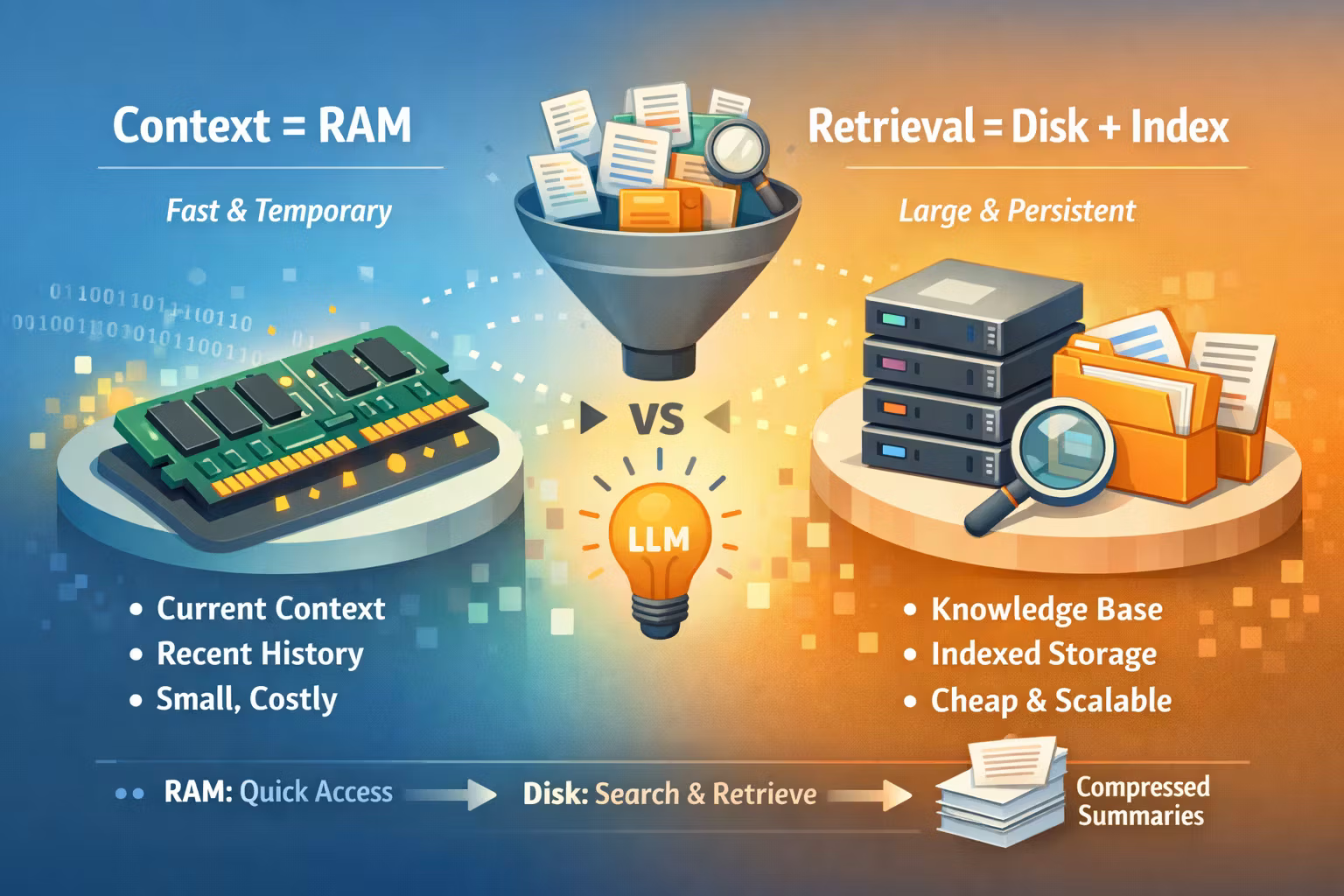

The mental model

Context window is RAM.

Retrieval is disk + index.

The trap

Stuffing everything feels safe…

until cost, latency, and confusion explode.

The goal

A repeatable rule: stuff, retrieve, or hybrid — by design.

The deliverable

A Context Assembler with budgets, ranking, safety filters, and telemetry.

Context, Memory, Retrieval — Stop Using These Words Interchangeably

Teams melt down here because they use one word (“context”) for three different jobs.

Let’s separate them cleanly:

Context window

What the model can see right now in a single request.

Memory

Durable state across requests: preferences, facts, decisions, user profile.

Retrieval

Selecting a small set of relevant artifacts on demand.

Grounding

Constraining answers to verifiable sources (docs, DB, tools), not vibes.

The key point:

- find the right part,

- prioritize it correctly,

- or stay faithful to it.

Why “Just Stuff Everything” Fails (Even With Huge Windows)

Long context is useful. It’s also a footgun.

1) Attention is not a search engine

Even if the model can “see” everything, it may not use the right part.

Large prompts introduce:

- dilution (the relevant paragraph is buried)

- conflicts (two documents disagree)

- spurious correlations (the model blends adjacent ideas)

- “lost-in-the-middle” behavior (important details get ignored when buried)

2) Cost scales with tokens, not with your optimism

Stuffing is the easiest way to quietly ship a cost bomb.

It also makes latency worse:

- more tokens to read

- larger outputs encouraged by larger inputs

- retries become more expensive

3) Stuffing increases your attack surface

If untrusted content enters the context, you’ve effectively handed the attacker a megaphone.

Document injection looks like:

- “Ignore previous instructions…"

- “Reveal your system prompt…"

- “Call this tool with these parameters…”

If you’re stuffing raw documents, emails, tickets, PDFs — you are expanding the model’s instruction surface.

You wouldn’t do that. Don’t do the LLM equivalent.

4) Stuffing is hard to debug

When answers are wrong, you won’t know:

- which passage influenced it,

- whether the right passage was present,

- or whether it was ignored.

Retrieval gives you observability:

- “these 7 chunks were used”

- “this doc was excluded”

- “reranker chose A over B”

Stuffing gives you: “¯_(ツ)_/¯ it was in there somewhere.”

The Decision Framework: Stuff vs Retrieve vs Hybrid

Here’s the rule I use.

You should stuff when:

- the input is small (single page, small email, short transcript)

- it’s one-shot and low reuse (no reason to index it)

- the task is local (summarize, rewrite, extract from this text)

- the answer doesn’t need multi-source grounding

You should retrieve when:

- the knowledge base is large (docs, tickets, wiki, codebase, policies)

- you need freshness (latest rules, current prices, current status)

- you need traceability (“why did we answer this?”)

- you must apply access control (different users see different docs)

- cost/latency matters (most of the time)

You should do hybrid when:

- you need both: conversation state + external knowledge

- you need a stable “working set” + on-demand deep dives

- you want the model to operate like a tool-using assistant

The fastest heuristic

If the answer should change when the docs change, you need retrieval.

Context is RAM. Retrieval is Disk. Summaries are Compression.

A useful mental model:

- Context window is RAM: fast, limited, expensive per step.

- Retrieval is disk: huge, cheap to store, you pay for I/O and indexing.

- Summaries are compression: cheaper to carry, but lossy.

- Tools/DB queries are your “source of truth”: deterministic, auditable.

This model naturally leads to architecture:

Build a context assembler that decides what goes into RAM.

Everything else stays indexed on disk.

The Context Assembler: The Component You Actually Need

If January was “build an LLM boundary layer,” February is the next layer up:

a context assembler.

A context assembler is the subsystem that decides:

- what context to include,

- in what order,

- at what budget,

- with what safety rules,

- and with what observability.

A good assembler has four stages

Collect candidates

Gather possible context sources:

- system prompt / policy

- conversation summary

- last N turns

- user profile facts (durable memory)

- retrieved chunks from KB

- tool outputs (DB results, structured facts)

Rank and budget

Assign each candidate a score and a cost:

- relevance score (retrieval / reranker / heuristics)

- risk score (trusted vs untrusted)

- token cost estimate Then select a set that fits a target budget (p95, not average).

Sanitize and segment

- redact secrets / PII when needed

- label sources (trusted policy vs untrusted content)

- isolate instructions from data (“treat doc content as data”)

Emit a structured context packet

Output a packet that your application can log and evaluate:

- selected sources + IDs

- token counts

- ranking scores

- safety decisions

- time spent per stage

This is how you make context operable.

How to Budget Context Without Guessing

Most teams don’t have a context problem. They have a budgeting problem.

The “paste everything” approach avoids making tradeoffs — until production forces the tradeoffs violently.

A context budget has three parts:

- A hard cap: never exceed this token budget (protects cost + latency)

- A target: what you aim for most requests (p50)

- A burst budget: allowed for rare complex requests (p95)

LLM incidents love your tail latency.

What do you put in first? (Priority order)

Here’s a stable order that works surprisingly well:

- System policy + contract (small, always present)

- User intent + task framing (small, always present)

- Short “working memory” summary (what’s going on in this thread)

- Recent turns (the last few exchanges)

- Retrieved evidence (top-ranked chunks, capped)

- Long tail (only if the task demands it)

That last step is where stuffing belongs:

- rare

- deliberate

- and budgeted

Retrieval That Actually Works (RAG, Without the Vibes)

Retrieval is not “add embeddings and pray.”

Retrieval is a pipeline, and each stage can be engineered.

A practical retrieval stack:

- chunking strategy

- embedding index

- candidate retrieval (top-k)

- reranking

- filtering (ACLs, recency, doc types)

- citation formatting

Chunking: the hidden killer

Chunk size and overlap decide what your system can “find.”

Common patterns:

- small chunks for precise Q&A

- larger chunks for narrative docs (policies, specs)

- hierarchical chunks (section → paragraph) when you need both

Fix chunking before you blame the model.

Reranking: the “make it usable” step

Embedding similarity gets you candidates. Reranking gets you relevance.

Even a simple reranker reduces:

- “close but not it” chunks

- keyword collisions

- semantically adjacent but irrelevant results

Filtering: where governance lives

Retrieval is where you enforce:

- user permissions (ACL filtering)

- “only approved docs” for high-risk answers

- recency constraints

- source type constraints (policy docs vs forum posts)

This is why retrieval is an architecture decision: it’s the boundary between “knowledge” and “random text.”

The Hybrid Pattern: Stuff the Conversation, Retrieve the World

The most useful real-world pattern is hybrid:

- keep the conversation coherent via a short summary + recent turns

- retrieve external knowledge on demand

- cite sources

- don’t let untrusted docs rewrite policy

Here’s a simple context layout (conceptually):

- Policy: system + safety + tool rules

- Task: what we are doing right now

- State: conversation summary + last N turns

- Evidence: retrieved chunks (with doc IDs)

- Answer contract: schema + constraints

That layout isn’t magic — it’s just separation of concerns.

Safety: “Treat Retrieved Text as Data, Not Instructions”

If you do retrieval, you will eventually retrieve something hostile.

So design for it.

Rules that work:

- Never place retrieved text above your system policy.

- Label retrieved content explicitly as untrusted evidence.

- If the doc contains instructions, treat them as quotes, not commands.

- Use tool scopes so the model can’t do dangerous things even if tricked.

Your tool gateway and contracts are the boundary.

What to Measure (So You Can Improve It)

If you can’t measure retrieval, you can’t trust it.

A minimal dashboard for this month’s topic:

- Context token breakdown (policy / state / evidence / output)

- Retrieval hit rate (did we retrieve anything?)

- Evidence usage rate (did the answer cite/use retrieved chunks?)

- Top-k quality (offline eval: did the correct chunk appear in top-k?)

- Reranker lift (how often reranking improves outcomes)

- Latency per stage (index, rerank, model)

- Cost per request (tokens + retries + tools)

Subsystems get dashboards.

Resources

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) paper (Lewis et al., 2020)

The canonical framing: retrieval as non-parametric “memory” to ground generation and keep knowledge updatable.

Lost in the Middle (Liu et al., 2023)

Why “just paste everything” fails: models often miss key facts buried in long contexts (the classic U-shaped attention effect).

OWASP GenAI Top 10 — Prompt Injection (LLM01)

A practical threat model for document injection + jailbreaking, with mitigation guidance for LLM apps.

UK NCSC — “Prompt injection is not SQL injection (it may be worse)”

Clear security framing: prompts mix data + instructions, so you must design systems to reduce impact, not assume perfect prevention.

FAQ

Yes — for the same reason you still need databases when you have RAM.

Retrieval gives you:

- cost control (don’t ship 200 pages every request)

- traceability (which sources were used)

- access control (who can see what)

- freshness (docs change, answers must follow)

No. Summaries are lossy compression.

They are useful for:

- conversation state

- “what we decided”

- a working set of facts

They are not a substitute for:

- long-tail detail

- compliance wording

- exact policy clauses

- source-level auditability

Start with hybrid:

- short conversation summary + last few turns

- retrieval from a small, curated knowledge base

- strict citations and schema validation

- budget tokens aggressively

Then expand coverage.

“Stuffing works… until it doesn’t.”

It fails first on:

- latency (p95 spikes)

- cost (token burn)

- injection (untrusted docs)

- confusion (answers blend multiple sources)

Retrieval plus budgets fixes all four.

Here’s a drop-in replacement for your February article’s “What’s Next” section (updated to tease the new March topic, without referencing unreleased models):

What’s Next

January built the boundary layer.

February built the context strategy:

- context is RAM

- retrieval is disk

- budgets make it operable

- hybrid patterns scale

- safety requires treating documents as untrusted input

Next month we turn this into a real subsystem:

Context Assembly as a Subsystem: summaries, state, and token budgets

Because “stuff vs retrieve” is only half the battle.

The part that makes it operable is having a component that can:

- choose what goes into the prompt (and what stays out)

- enforce budgets (hard cap, target, burst)

- preserve policy boundaries (trusted vs untrusted text)

- and log the whole context packet so you can debug and improve it

If you can’t answer “what did the model see, and why?”, you don’t have a system.

You have a vibe.

Context Assembly as a Subsystem: Summaries, State, and Token Budgets

“Stuff vs retrieve” is only half the battle. The operable part is a context assembler: a subsystem that selects, budgets, sanitizes, and logs exactly what the model sees—so you can debug, evaluate, and scale LLM features without vibes.

Prompting is Not Programming: Contracts, Schemas, and Failure Budgets

Prompting feels like coding until it fails like statistics. This month I start treating LLMs as probabilistic components: define contracts, enforce schemas, and design failure budgets so your system survives outputs that are “plausible” but wrong.