Model Selection Becomes Architecture: Routing, Budgets, and Capability Tiers

The moment you have multiple models with different strengths, “pick the best model” turns into system design. This month is a practical blueprint for routing, fallbacks, and budget-aware capability tiers—without turning your stack into an untestable mess.

Axel Domingues

January gave us the boundary layer: contracts, schemas, failure budgets.

February made context explicit: stuff vs retrieve.

March turned it into software: context assembly as a subsystem, with Context Packets you can replay.

Now the next uncomfortable truth arrives:

In production, “the model” is not a single choice.

It’s a portfolio—and a router.

The moment you have multiple models available (different costs, latencies, modalities, safety properties, and accuracy profiles), you stop asking:

“Which model is best?”

And start asking:

“What model is best for this contract, under this budget, with this risk tier… and what happens when it fails?”

This is the month where model selection becomes architecture.

The shift

You’re not choosing a model. You’re designing routing + fallbacks.

The abstraction

Every request is a contract: task, schema, risk tier, budget tier.

The control surface

Routing is driven by capability tiers + policy constraints.

The operator view

Reliability is measured in p95, cost, retries, and error modes.

Why “Pick the Best Model” Is the Wrong Question

In a lab, you can chase a single score.

In production, you’re optimizing a vector:

- correctness (for the contract, not vibes)

- latency (p95 and tail behavior)

- cost (including retries and long contexts)

- safety (tool permissions, refusal compliance, injection robustness)

- modality needs (text-only vs image/audio/video)

- availability (outages, rate limits, regional constraints)

- governance (data residency, auditability, vendor constraints)

The right question is:

What is the minimum capability that reliably satisfies this contract, inside the failure budget?

That sentence is architecture.

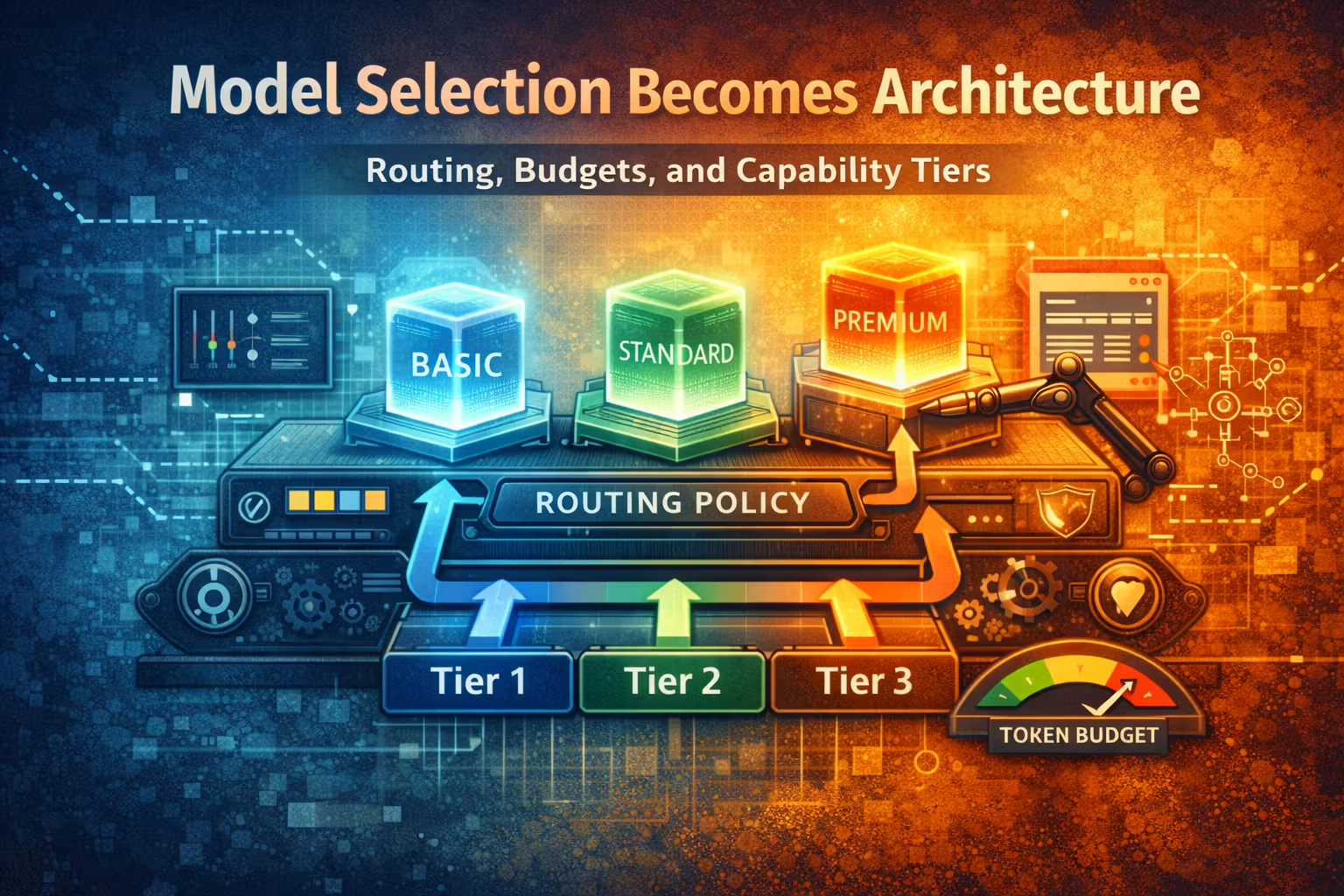

The Core Idea: Capability Tiers (Not “Small vs Big”)

Instead of thinking in brand names, think in capability tiers.

A tier is defined by measurable properties:

- supported modalities

- max input/output tokens

- tool-use reliability

- reasoning quality (for your task suite)

- safety behavior (for your policies)

- median + p95 latency

- cost per million tokens

- quota and availability profile

You can swap the underlying model later without breaking your app— as long as the tier contract holds.

A simple tiering scheme

- Tier S (fast/cheap): classification, extraction, light rewriting, routing decisions

- Tier M (balanced): most user-facing drafts, structured outputs, moderate reasoning

- Tier L (premium): hard reasoning, long context synthesis, high-stakes drafts

- Tier X (specialized): multimodal, code-heavy, domain-tuned, or policy-hardened

The exact number doesn’t matter.

What matters is that tiers are stable interfaces.

Routing Is a Policy Decision, Not a Developer Preference

Model choice should not live inside random call sites.

It belongs in the same place as:

- auth rules

- tool allowlists

- PII policies

- schema requirements

- failure budgets

In other words: policy.

So we introduce a new actor in the system:

the Model Router.

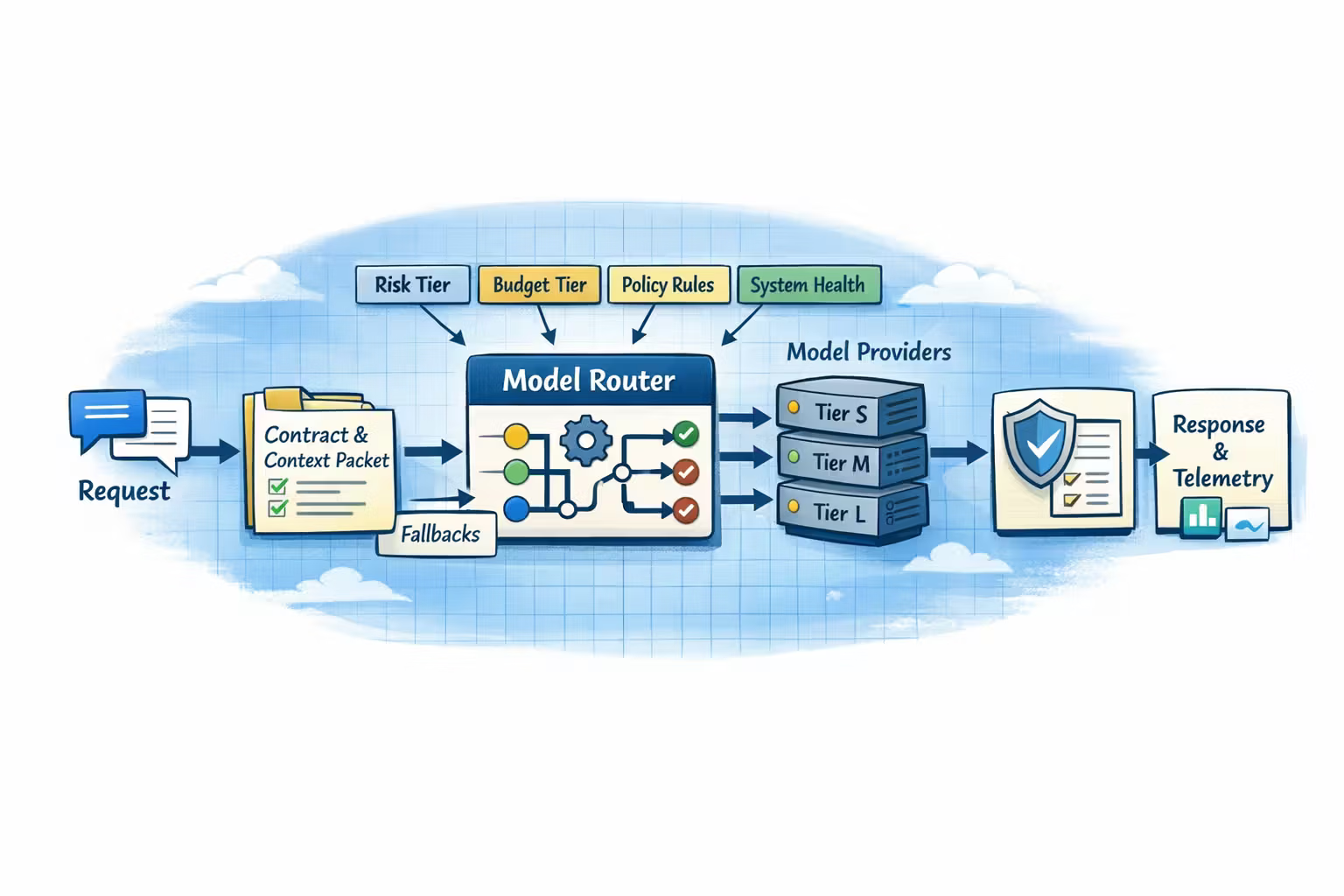

The Model Router: What It Does (and What It Must Log)

A model router is a service (or module) that decides:

- which tier to use

- which provider/model within the tier

- what fallbacks are allowed

- when to degrade gracefully vs fail fast

Router inputs

- task name (from your contract)

- risk tier (low/med/high)

- budget tier (bronze/silver/gold)

- context packet stats (tokens, evidence count, tools requested)

- policy constraints (data type, residency, “no external calls”, etc.)

- current system state (provider health, quotas, outage flags)

Router outputs

- selected model (or provider + model id)

- allowed fallback set

- timeout and retry policy

- tool permissions (tightened when needed)

- decision reason (for logs)

Every routing decision should be logged as a structured event.

The Contract Drives the Tier

In January we insisted on contracts and schemas.

Here’s the extension:

Model tier becomes part of the contract.

Not as a hard-coded choice, but as a constraint set.

Example: task contract (conceptual)

{

"task": "invoice_support_reply",

"risk_tier": "high",

"output_schema": "SupportReplyV2",

"budget_tier": "silver",

"min_capability_tier": "M",

"max_capability_tier": "L",

"allowed_tools": ["kb_search", "crm_lookup"],

"disallowed": ["send_email", "refund_payment"]

}

This pushes model selection into the same governance path as everything else.

Routing Patterns That Actually Work

Most teams end up using a small set of patterns.

Here are the ones worth building intentionally.

Use when: tasks are stable and you want predictability.

- “Support reply” always uses Tier M

- “Legal rewrite” always uses Tier L

- “Tagging” always uses Tier S

Pros: simple, debuggable, stable costs

Cons: may overpay for easy requests

Use when: you have paid plans or internal cost controls.

- bronze → Tier S/M

- silver → Tier M

- gold → Tier M/L

Pros: product-friendly, easy to explain

Cons: budget tier becomes a product dependency (manage carefully)

Use when: you can detect failure reliably.

- try Tier S

- validate output (schema + heuristics)

- if fail → Tier M

- if still fail → Tier L

Pros: saves cost while keeping quality

Cons: requires strong validators and careful latency budgets

Use when: inputs vary wildly and you need smarter selection.

A Tier S model classifies:

- complexity

- risk

- “needs retrieval” vs not

- “needs multimodal” vs not

Then routes to the right tier.

Pros: flexible, can reduce overuse of Tier L

Cons: easy to build a flaky router; must be evaluated like any other model

Use when: you’re migrating or testing providers.

- send 5% traffic to candidate

- compare correctness + latency + cost

- auto-disable on regressions

Pros: safe evolution

Cons: needs metrics and kill switches

Fallbacks: The Difference Between “Smart” and “Operable”

Fallbacks are not a “retry.”

Fallbacks are a design decision about what failure is acceptable.

Define failure modes explicitly

- provider timeout

- rate limit

- safety refusal

- schema violation

- missing citations / missing evidence usage

- tool call failure

- low confidence (if you have a confidence proxy)

Then map them to behavior:

- degrade (cheaper model, shorter context, no tools)

- upgrade (higher tier, stricter reasoning)

- fail fast (high-risk task + low trust input)

- ask a question (interactive resolution)

- hand off to human (if applicable)

If the system degrades quality, that should be visible to:

- telemetry

- and sometimes the user experience (depending on the product)

Latency and Cost: Routing Without Budgets Is Just Gambling

A model router without budgets will “work” until it meets real traffic.

The budgets that matter in routing

- p95 end-to-end latency (not just model time)

- max retries (per request and per stage)

- max upgrade hops (how many tiers can we climb)

- max input tokens (context assembly cap)

- max tool calls (tools are latency multipliers)

- max cost per request (hard ceiling)

This is where March’s Context Packet becomes essential.

Because routing needs visibility into:

- token count (actual, not guessed)

- tool needs (requested + allowed)

- evidence count (how much retrieval is happening)

A Practical Router Decision Tree (You Can Implement Tomorrow)

This is not “AI.” It’s operations.

Start from the contract

- task name

- risk tier

- output schema

- allowed tools

- budget tier

Compute a context profile

From the Context Packet:

- input tokens

- evidence tokens

- tool count requested

- “untrusted evidence” present? (usually yes)

Choose the minimum tier that fits the contract

- If high-risk: minimum Tier M (often)

- If tool-heavy: require a tier with proven tool reliability

- If long-context: require a tier with stable long-context behavior

Apply budget gating

- bronze may cap at Tier M

- gold may allow Tier L

Apply health constraints

- if provider A is degraded, route to provider B within same tier

- if both degraded, degrade tier or fail fast depending on risk

Define fallback policy

- max upgrades: 1 (usually)

- retries: 1–2 with jitter

- timeouts: tier-specific

- schema validation required

Emit and log the routing decision

Store:

- selected tier/model

- reason codes

- budgets

- fallback set

Testing: You Must Evaluate the Router, Not Just the Models

The router changes outputs as much as the model does.

So you need evaluations at three levels:

Model eval

Per-tier task accuracy, formatting reliability, refusal behavior.

Router eval

Does it choose the right tier? Does it avoid over-upgrading?

System eval

End-to-end contract satisfaction: cost, latency, safety, correctness.

Drift monitoring

Quality changes over time due to providers, prompts, and data.

Router evaluation is surprisingly concrete

You can label a dataset with:

- input complexity class

- required tier (S/M/L)

- allowed tools

- acceptable cost ceiling

Then measure:

- accuracy of routing

- upgrade frequency

- degradation frequency

- impact on success rate and p95

If you can’t evaluate it, don’t let it decide.

Governance: Separating Product Choice From Engineering Choice

Once you have tiers, product and engineering can collaborate cleanly:

- Product defines budget tiers and user entitlements

- Engineering defines capability tiers and contracts

- Security defines risk tiers and tool allowlists

- Ops defines SLOs and kill switches

Everyone gets a knob that maps to their responsibility.

That’s what good architecture does.

Common Failure Modes (Multi-Model Edition)

Likely cause: silent upgrades to higher tiers, or retries multiplying tokens.

Fix: hard cost ceiling per request + log upgrade reasons + cap upgrade hops.

Likely cause: cascades without latency budgets, or tool calls in the critical path.

Fix: per-tier timeouts + staged budgets + “no tools” degrade mode.

Likely cause: tier switching changes tone and failure patterns.

Fix: shared contracts + style constraints + deterministic render + tier-specific prompts.

Likely cause: no provider-level health routing or kill switches.

Fix: health-aware routing + circuit breakers + safe degrade mode.

Likely cause: routing to cheap tiers under pressure, or missing evidence enforcement.

Fix: risk-tier rules: minimum tier + mandatory evidence + stricter validation.

A Template You Can Copy: “Tier Rules” as Configuration

Don’t bury tier logic in code if you can avoid it.

Make it a config artifact you can review and version.

tiers:

S:

max_input_tokens: 4000

max_tools: 0

timeout_ms: 1500

retries: 1

M:

max_input_tokens: 8000

max_tools: 3

timeout_ms: 2500

retries: 1

L:

max_input_tokens: 16000

max_tools: 5

timeout_ms: 4000

retries: 2

tasks:

classify_ticket:

min_tier: S

max_tier: M

risk_tier: low

draft_support_reply:

min_tier: M

max_tier: L

risk_tier: medium

generate_refund_decision:

min_tier: L

max_tier: L

risk_tier: high

require_evidence: true

require_schema: true

Make critical behavior reviewable and testable as configuration, not folklore.

FAQ

If you have one model and a toy use case, yes.

If you have:

- multiple tasks,

- paid plans,

- tools,

- or any real reliability requirement,

you will rebuild this anyway—either intentionally or in panic.

Build the concept first:

- contracts

- tiers

- budgets

- logs

- fallback policy

The implementation can be a small module or a service.

Frameworks help, but they don’t decide your budgets or risk rules for you.

Keep constants stable:

- contract structure

- deterministic render style

- schema validation

- tone constraints

Let tiers differ mainly in capability, not personality.

What’s Next

April made model choice explicit:

- capability tiers become an interface

- routing becomes policy

- fallbacks become design

- budgets become enforceable

- the router becomes evaluable and observable

Next month we tackle the part everyone rushes into—and then regrets:

Open Weights in Production: evaluation, licensing, and guardrails

Because once you can route between models, you’ll inevitably ask:

When do I host my own—and what does “production-safe” mean when the weights are mine?

Open Weights in Production: evaluation, licensing, and guardrails

Open weights shift your risk from vendor to you. This month is the playbook: evaluate like a product, treat licensing as architecture, and ship with guardrails that survive real users.

Context Assembly as a Subsystem: Summaries, State, and Token Budgets

“Stuff vs retrieve” is only half the battle. The operable part is a context assembler: a subsystem that selects, budgets, sanitizes, and logs exactly what the model sees—so you can debug, evaluate, and scale LLM features without vibes.