Microservices vs Modular Monolith: The “When” and the “How”

Microservices aren’t a flex — they’re a tax. Modular monoliths aren’t “temporary” — they’re often the best architecture. Here’s the decision framework, the failure modes, and the migration path that doesn’t create a distributed mess.

Axel Domingues

Microservices became popular for a good reason:

They solve real problems.

They also create real problems.

And a lot of teams adopt them for the wrong reason:

“We want to be modern.”

This month is about replacing ideology with engineering.

Not “microservices bad” or “monolith bad”.

Just the adult question:

When should you split a system — and how do you do it without building a distributed monolith?

- Monolith in this article means: one deployable unit.

- Modular monolith means: one deployable with hard internal boundaries (modules, ownership, dependency rules).

- Microservices means: multiple deployables, each owning a slice of the domain and usually its data.

- Distributed monolith means: microservices-shaped deployment with monolith-shaped coupling (the worst of both).

The real goal

Ship changes safely, at the speed your business needs.

The real constraint

Every architectural choice creates a tax (complexity, ops, coordination).

The usual failure

Teams pay the microservices tax before they need the microservices benefits.

The “grown-up” path

Start with boundaries. Split only when boundaries + teams demand it.

The One Question That Makes the Decision Obvious

If you only remember one line, remember this:

Microservices are a scaling strategy for teams, not a scaling strategy for CPUs.

Yes, services can scale independently. But independent scaling is rarely the first problem you have.

The first problem is usually one of these:

- releases collide (teams block each other)

- the codebase becomes un-navigable

- data consistency becomes fragile

- incident response becomes slow

- “small change” becomes “multi-week migration”

Those are organizational + architectural problems — and they can be solved (for a long time) inside a modular monolith.

First Principles: What You Pay For

What you gain with a modular monolith

- Single deployment: fewer moving parts, easier debugging.

- Strong consistency is cheap: one database transaction can be “the truth”.

- Local reasoning: you can run the whole system on your laptop.

- Change velocity early: great while you’re still learning the domain.

What you gain with microservices

- Independent deployments: teams can ship without coordinating every release.

- Blast-radius control: failures can be isolated (if you design for it).

- Focused ownership: teams can “own a slice” end-to-end.

- Technology flexibility: sometimes useful, often overplayed.

What you always pay for with microservices

- Distributed data reality: cross-service consistency is hard.

- Operational overhead: CI/CD, observability, on-call, incident workflows.

- Network failure: latency, timeouts, retries, partial failures.

- Coordination moves: from “shared code” to “shared contracts”.

- solid CI/CD

- observability you trust

- a real on-call culture

- explicit ownership boundaries

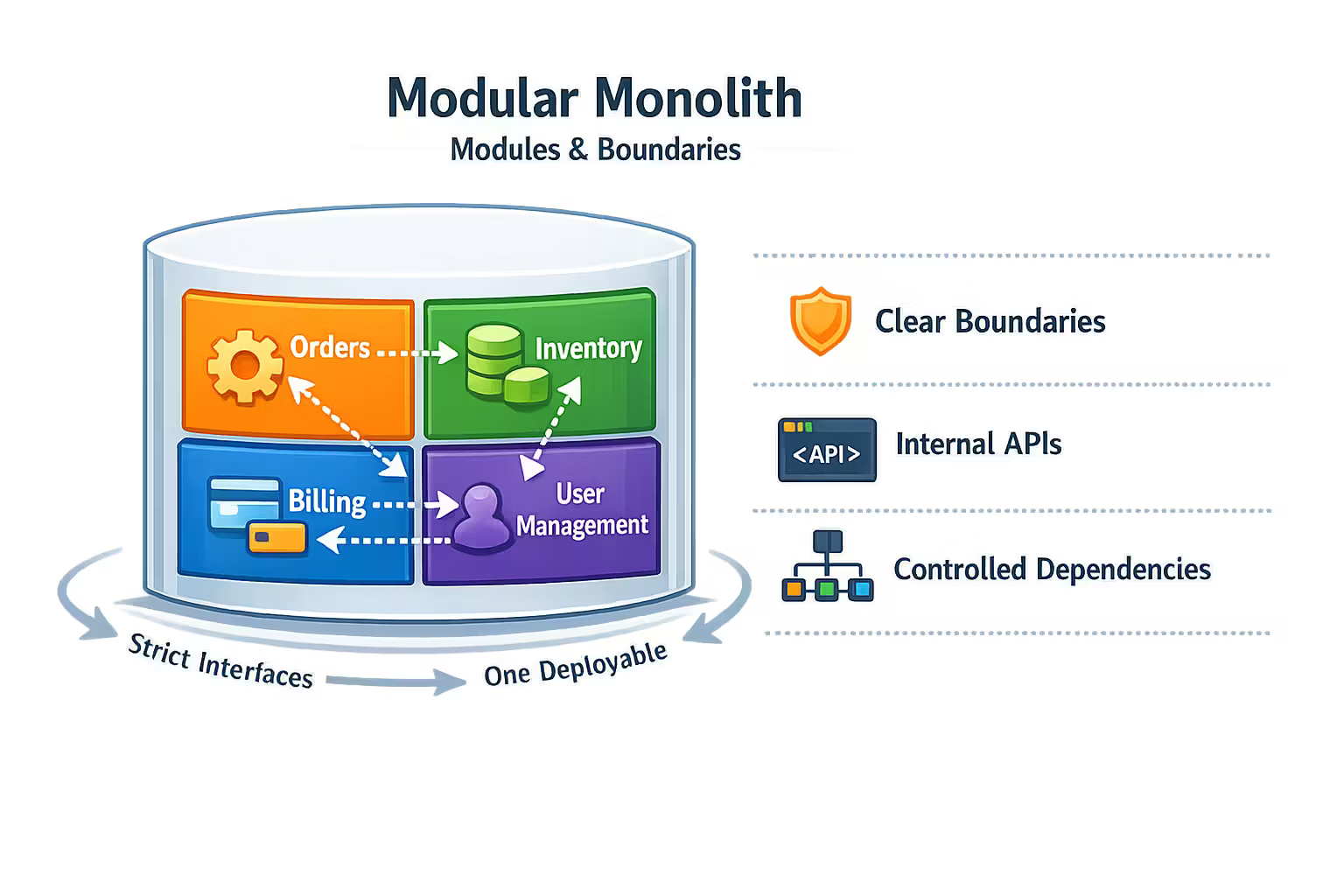

The Modular Monolith Done Right

A modular monolith is not “one big ball of mud”.

It’s a monolith that behaves like a set of internal services:

- explicit boundaries

- clear ownership

- dependency rules

- domain-driven interfaces

The pattern

- Slice by bounded context / business capability, not by technical layers.

- Own dependencies inside a module (UI + domain + persistence, behind an interface).

- Expose only what must be shared (domain services, not raw tables).

- Enforce boundaries in code review and tooling (lint rules, dependency graphs).

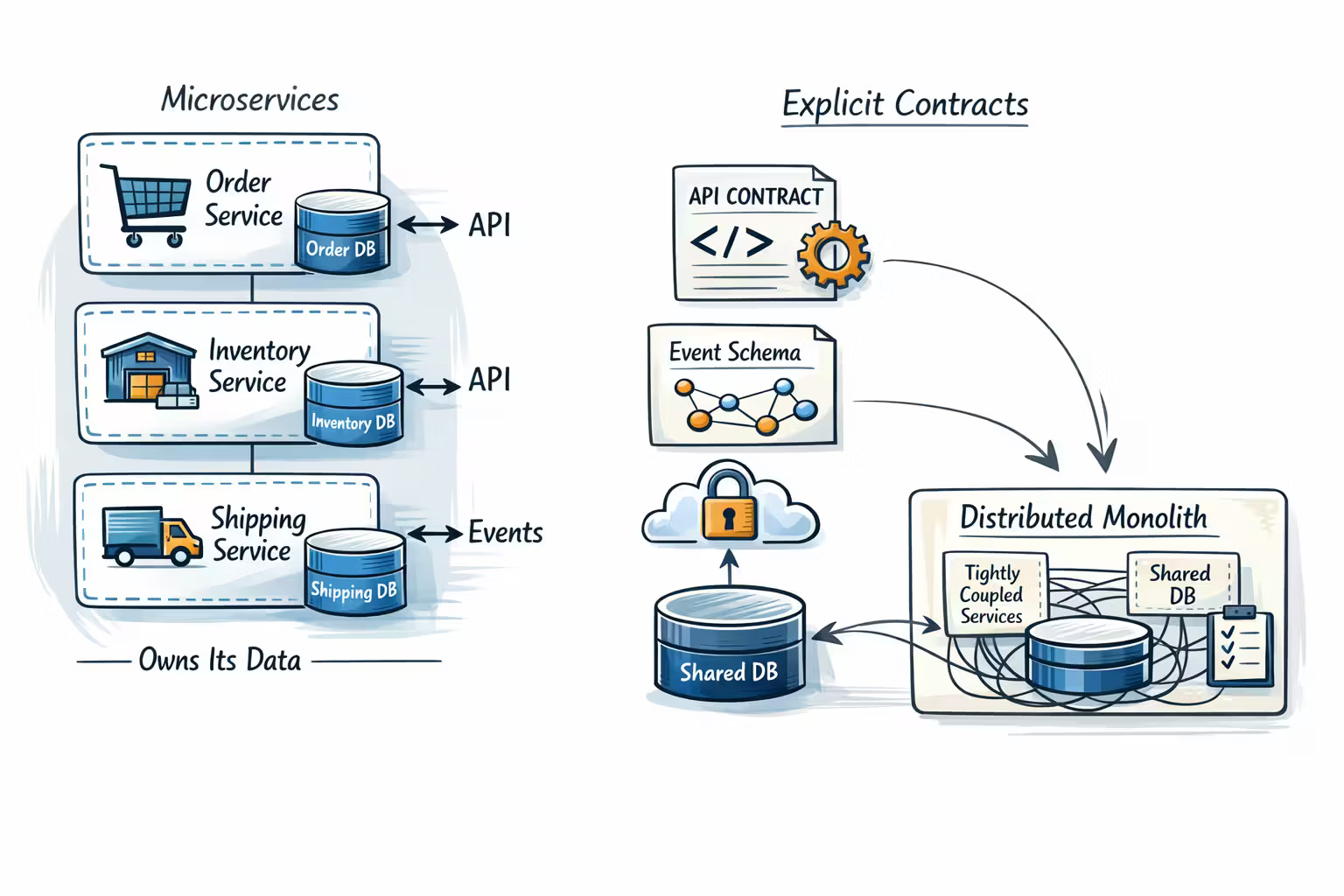

The Microservices Done Right

Microservices are not “many small apps”.

They’re a decision to accept:

- network failures

- distributed consistency

- independent operations

…and to build the discipline to survive that world.

The non-negotiables

- A service owns its data.

- No shared database tables across services.

- No synchronous call chains where Service A waits on B waits on C.

- Idempotency everywhere (because retries happen).

- Contracts as products (because you broke compile-time coupling).

When to Choose Which: A Practical Decision Framework

Let’s make the decision concrete.

Choose a modular monolith when…

- You are still discovering the domain (requirements change weekly).

- You have one team (or a few teams) shipping in the same cadence.

- Your biggest risk is product risk, not scaling risk.

- You need strong consistency across flows (money, inventory, compliance).

- You don’t yet have operational maturity to run many deployables.

Choose microservices when…

- You have multiple teams that are truly independent in business scope.

- Release coordination is now a chronic bottleneck.

- You have stable bounded contexts and clear ownership.

- You need different scaling profiles for distinct capabilities.

- You can afford the platform/ops tax (or you already pay it).

Modular monolith fits

Early product phase, domain discovery, fewer teams, strong consistency needs.

Microservices fit

Multiple teams with stable boundaries + real need for independent deploys.

The Trap: “We Need Microservices Because Our Monolith Is Bad”

Most “microservices migrations” are actually this:

We have a bad monolith, so we’ll fix it by adding distributed complexity.

That almost always makes it worse.

A bad monolith is fixed by:

- boundaries

- ownership

- modularization

- tests

- deployment discipline

Those are the same prerequisites for microservices — but cheaper to learn in one deployable.

The actual disease is a lack of boundaries and engineering discipline.

The Two Failure Modes You Must Recognize Early

You have “services”, but:

- changes require touching many services

- deployments must be coordinated

- incidents cascade across the fleet

- services share a database or schema assumptions

- synchronous call chains create “brownouts”

Diagnosis: the boundaries are wrong or the domain is still changing too fast.

Teams extract microservices, but keep everything “consistent” via shared libraries:

- shared domain models

- shared validation rules

- shared persistence utilities

Now every change becomes a multi-repo release train.

Diagnosis: coupling moved from codebase coupling to dependency coupling.

The Migration Path That Doesn’t Create Chaos

There’s a sane, repeatable path that works for most systems:

- Build boundaries inside the monolith first.

- Extract only the seams that demand independent deployment.

- Keep contracts explicit and integration testable.

Here’s how.

Step 1: Make the monolith modular (for real)

- Group by business capability (bounded context), not by layers.

- Introduce module interfaces and “internal APIs”.

- Enforce dependency direction (e.g., domain → application → adapters).

- Add an architectural test suite (dependency rules, forbidden imports).

Step 2: Introduce an edge/API boundary

- Treat your public API as a product.

- Use an API gateway or BFF if needed.

- Hide internal implementation (monolith or services) behind stable endpoints.

- Add contract tests (consumer-driven, if you can).

Step 3: Extract a service that has clean ownership

Pick a candidate that:

- owns its data naturally

- has clear SLAs

- has limited cross-domain transactions

Common first candidates:

- notifications

- search

- reporting/analytics ingestion

- media processing

- auth/identity (sometimes, with caution)

Step 4: Solve distributed data with an explicit pattern

- Avoid “two-phase commit fantasies”.

- Use outbox for reliable event publication.

- Use sagas/workflows for long-running business processes.

- Design idempotent handlers and compensations.

Step 5: Repeat — but only when the boundary proves itself

If extraction didn’t reduce coordination or improve resilience, don’t keep splitting blindly. Fix the boundary first.

It’s “extract the parts where independent change is worth the cost”.

Guardrails: How to Keep a Modular Monolith Healthy

A modular monolith rots when boundaries become social agreements instead of enforced rules.

Use these guardrails early:

Own your module

Named team ownership. Clear entry points. “Who maintains this?” must have an answer.

Enforce dependencies

Tooling + tests that fail builds when dependency rules are violated.

Stop leaking tables

Access data via module interfaces, not cross-module queries.

Ship with discipline

CI gates, fast tests, rollback strategy. Operational discipline is architecture.

Guardrails: How to Keep Microservices from Eating You

The “microservices tax” is paid in operations and coordination.

To avoid death-by-a-thousand-services:

1) Keep services coarse enough to own outcomes

If a service can’t be owned end-to-end by a team, it’s probably too small.

2) Prefer async integration for cross-domain flows

Synchronous is fine within a boundary. Across boundaries, prefer events and workflows to avoid call chains.

3) Build a platform “golden path”

Teams shouldn’t reinvent:

- logging

- metrics/tracing

- deployment

- retries/backoff

- secrets/config

- local dev story

4) Treat contracts as first-class

- version your public interfaces

- publish schemas

- add compatibility tests

- make breaking changes visible early

That’s expensive — and it burns teams out.“Everyone maintains their own mini-production.”

A Simple Heuristic That Works Surprisingly Well

If you’re undecided, use this:

- Start modular.

- Split when teams need autonomy AND boundaries are stable.

- Split with a plan for distributed data.

Or even more blunt:

If you can’t clearly name the bounded contexts, you’re not ready for microservices.

Cheat Sheet: The “Should We Split?” Checklist

- Are multiple teams blocked by release coordination?

- Do you have stable ownership boundaries?

- Is the domain model stable enough to survive contract separation?

- Do you have CI/CD + observability that supports many deployables?

- Can you afford increased on-call and incident surface area?

- Does the service own its data end-to-end?

- Can it be deployed independently without coordinated releases?

- Does it avoid synchronous call chains for core business flows?

- Are interfaces explicit (schemas/contracts) with versioning strategy?

- Are handlers idempotent and safe under retries?

Resources

Team Topologies

A clear model for team boundaries and why architecture is often a reflection of communication paths.

Domain-Driven Design

Bounded contexts are the missing vocabulary in most “microservices vs monolith” debates.

FAQ

Not necessarily.

Many high-scale companies run modular monoliths successfully for years — sometimes permanently — because the economics are great:

- one deployable

- strong consistency is cheap

- debugging is simpler

If your team topology and domain boundaries don’t demand microservices, a modular monolith can be the best long-term architecture.

You can, but you’ll reinvent the pain.

DDD isn’t an ideology — it’s vocabulary:

- bounded contexts

- ubiquitous language

- explicit boundaries

Without that, teams tend to split by technical layers, and coupling returns immediately via data and workflows.

Distributed data.

The moment a business flow spans multiple services, you need:

- sagas/workflows

- idempotency

- retries + compensations

- observability across boundaries

If you ignore that cost, the system still pays it — just as outages.

What’s Next

If microservices vs modular monolith is the “shape” question…

…the next question is:

How do you ship any shape reliably?

In January 2022, we go operational:

“Containers, Docker, and the Discipline of Reproducibility”

Because once you have multiple deployables (or even one), deployment discipline becomes architecture.

Containers, Docker, and the Discipline of Reproducibility

Containers aren’t “how you deploy apps” — they’re how you make environments stop being a variable. This is the operational discipline: immutable artifacts, repeatable builds, and runtime contracts you can actually rely on.

Queues, Retries, and Idempotency: Engineering Reality in Async Systems

Async work is where production gets honest. This month is a practical playbook for queues, retries, idempotency keys, and the patterns that keep “background jobs” from duplicating money or burning trust.