Exercise 1 - Linear Regression From Scratch

Notes from Andrew Ng’s ML course — plot the food-truck dataset, implement computeCost + gradientDescent in Octave, and build intuition with J(theta) visualizations.

Axel Domingues

Exercise 1 is where Machine Learning stopped feeling like a set of lecture slides and started feeling like a system I can debug.

The assignment story is simple: a food-truck chain wants to decide which cities to expand to. We have historical data and we want to predict profit from population.

But what you’re really learning is the core loop you’ll repeat for most ML models:

- represent data as matrices

- define a cost (how wrong you are)

- minimize it (how you learn)

- monitor convergence (how you don’t lie to yourself)

What you’ll build

A working linear regression loop in Octave: load data → build X → compute cost → run gradient descent → visualize fit & convergence.

Skills you practice

Vectorization, shape sanity-checks, training telemetry (J_history), and building intuition with the cost “bowl”.

Checkpoints (don’t skip)

- With

theta = [0; 0], expect J ≈ 32.07 J_historyshould decrease (not explode)- Learned line should match the scatter trend

What’s inside Exercise 1

The starter bundle is structured around a script that guides you step-by-step and a few functions you complete.

ex1.m— main script (single-variable linear regression)ex1data1.txt— dataset (population vs profit)warmUpExercise.m— Octave warm-upplotData.m— scatter plot helpercomputeCost.m— compute cost for linear regressiongradientDescent.m— run batch gradient descentsubmit.m— Coursera submit script

Skim the “Dataset” section once, then follow the walkthrough step-by-step. If anything breaks: jump to the “Debugging checklist” at the end.

The dataset (read this once, save hours later)

ex1data1.txt has two columns:

x: population of the city (in 10,000s)y: profit (in $10,000s)

Here,

x and y are both in 10,000s (population and dollars).Negative profit means the truck is losing money.

Before coding anything: open the .txt and sanity-check a few rows. If you misread units, you can build a “perfect” model that answers the wrong question.

Walkthrough (do it in this order)

Warm-up: “Hello, Octave”

The warm-up is intentionally tiny: return a 5×5 identity matrix.

A = eye(5);

I like this because it confirms the full edit → run → submit loop works before you touch ML logic.

Plot the data (don’t code blind)

If you only do one thing before implementing learning, do this.

In plotData.m, plot x vs y as a scatter plot.

plot(x, y, 'rx', 'MarkerSize', 10);

ylabel('Profit in $10,000s');

xlabel('Population of City in 10,000s');

What I’m looking for:

- does it look roughly linear?

- are there obvious outliers?

- are values in the expected ranges?

Exercise 1’s data looks “linear enough” that a straight line is a reasonable first model.

Build the design matrix X (the Octave mindset)

In this course, you learn to think in matrices early.

For single-variable linear regression, you construct X like this:

- first column: all ones (intercept term)

- second column: the feature values

x

m = length(y);

X = [ones(m, 1), x];

theta = zeros(2, 1);

From now on, predictions are just:

predictions = X * theta;

No loops. Cleaner code. Fewer bugs.

Implement computeCost.m (the contract)

computeCost returns a single number: how wrong your current parameters are.

In plain terms:

- predict all outputs with current

theta - compute the errors (prediction minus actual)

- square them

- average them (with the standard scaling used in the course)

A clean vectorized implementation:

function J = computeCost(X, y, theta)

m = length(y);

predictions = X * theta;

errors = predictions - y;

J = (1/(2*m)) * (errors' * errors);

end

The single most useful sanity check

With theta = [0; 0], the exercise expects the cost to be approximately:

J ≈ 32.07

If you don’t get close to that, stop and fix computeCost.m first.

Gradient descent depends on computeCost. If the cost is wrong, “learning” will look like random parameter motion.

Implement gradientDescent.m (the learning loop)

Now we update theta iteratively.

The provided script uses:

alpha = 0.01iterations = 1500

In gradientDescent.m, you:

- compute current errors

- update theta (simultaneously)

- store cost into

J_history

Vectorized implementation:

function [theta, J_history] = gradientDescent(X, y, theta, alpha, num_iters)

m = length(y);

J_history = zeros(num_iters, 1);

for iter = 1:num_iters

errors = (X * theta) - y;

theta = theta - (alpha/m) * (X' * errors);

J_history(iter) = computeCost(X, y, theta);

end

end

What “working” looks like

J_historydecreases over time- the final line fits the trend on the scatter plot

- your predictions for new

xvalues look plausible

Print cost every ~50 iterations while debugging. This is your training telemetry.

Plot the fitted line on top of the data

Once theta is learned, ex1.m plots the learned line over the scatter plot.

This is the first “wow” moment:

- a couple of functions

- some matrix operations

- and suddenly the computer learns a relationship from data

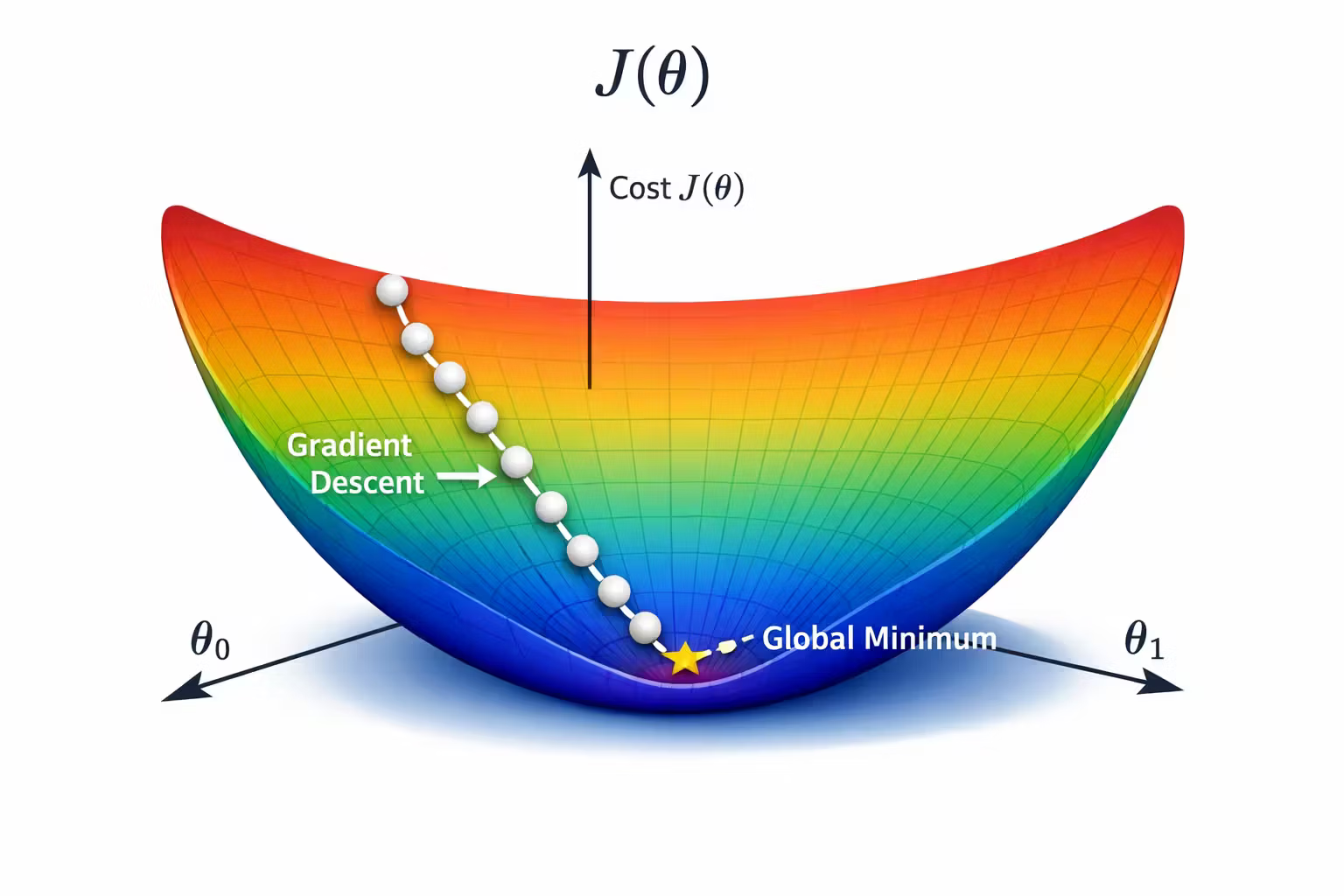

Visualize the cost surface (why gradient descent works here)

The script explores a grid of parameter values and plots:

- a 3D surface of the cost

- a contour plot

The key intuition you should walk away with:

- for this problem, the cost behaves like a smooth bowl

- there’s a clear lowest point (the best

theta) - gradient descent moves downhill toward that point

This visualization is why I like Exercise 1: it forces intuition, not just passing tests.

Debugging checklist (fast fixes)

Print sizes:

size(X)size(theta)size(y)

You want X * theta to produce an m x 1 vector.

*is matrix multiplication.*is element-wise multiplication

If your math is correct but results look crazy, this is a prime suspect.

In Octave:

theta(1)is the intercept termtheta(2)is the slope

- Too big: cost explodes →

Inf/NaN - Too small: cost decreases painfully slowly

UseJ_historyas your telemetry, not vibes.

If computeCost is wrong, gradient descent can “run” but learn nonsense.

Use the checkpoint J ≈ 32.07 early.

What I’m keeping from Exercise 1

- Plotting isn’t optional — it’s part of the model.

- The cost function is the contract. Validate it early.

- Training needs telemetry (

J_history), not hope. - Vectorization makes the code mirror the math and reduces bug surface.

- Visualizing the cost landscape makes gradient descent intuitive.

Mini-experiments (10 minutes each)

- Change

alphato0.1and watch what happens toJ_history. - Change

alphato0.001and compare how fast the cost drops. - Print

thetaevery ~200 iterations and see how it stabilizes.

What’s Next

In the next post, we level up from one input to many: Multivariate Linear Regression.

You’ll extend linear regression to multiple features, learn feature scaling + mean normalization to make gradient descent behave, and stop writing slow loops by vectorizing everything.

Linear Regression With Multiple Variables (and Why Vectorization Matters)

Notes from Andrew Ng’s ML course — extend linear regression to multiple features, learn feature scaling/mean normalization, and stop writing slow loops by vectorizing everything.

Why I’m Learning Machine Learning

In 2016, I’m documenting my journey through Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning course—building intuition, writing Octave code, and learning how to think in data.