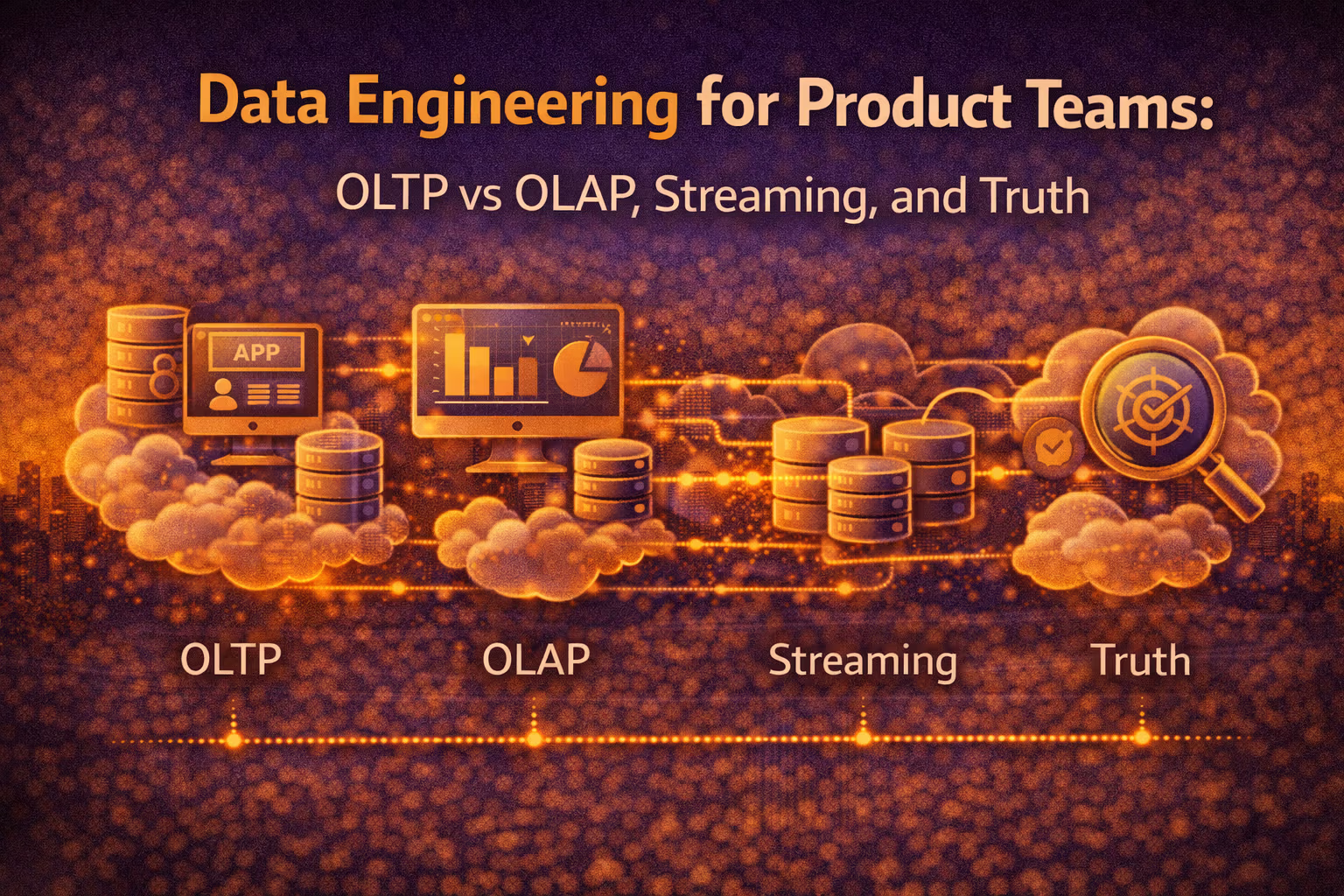

Data Engineering for Product Teams: OLTP vs OLAP, Streaming, and Truth

Most “data problems” are actually truth problems. This month is a practical mental model for product teams: where truth lives, how it moves, when to stream, when to batch, and how to keep analytics useful without corrupting production.

Axel Domingues

Most product teams don’t need “a data platform.”

They need answers that don’t lie.

And the uncomfortable reality is this:

If you can’t agree on what is true, you will never agree on what to build.

Because every dashboard, experiment, alert, and ML feature is a vote about truth:

- what happened

- when it happened

- who is authoritative

- and which version of reality you’re allowed to use

September is about a mental model that scales past “throw it in BigQuery/Snowflake and pray.”

OLTP vs OLAP is the starting point.

But the real point is: truth.

The goal this month

Give product teams a crisp model for operational vs analytical truth, and how data moves between them without breaking.

The punchline

Most teams don’t have a data problem.

They have a truth boundary problem.

The tools

OLTP, OLAP, event streams, CDC, batch, metrics layers — treated as tradeoffs, not ideology.

The deliverable

A practical playbook: decision rules, checklists, and the “don’t corrupt production truth” contract.

The 4 Kinds of Truth You Must Not Confuse

Before OLTP vs OLAP, separate truth domains. This is the root of most data pain.

Operational truth

What the product committed to users: orders, balances, access, permissions. Must be correct and auditable.

Analytical truth

What the business believes happened after processing: metrics, cohorts, revenue, retention. Must be consistent and explainable.

Observational truth

What we observed about the system: logs, traces, events, clickstreams. Noisy but invaluable for debugging and behavior.

Experimental truth

What happened under a treatment: exposure logs, assignment, attribution. Easy to poison if definitions drift.

If your analytics pipeline can change past “revenue” in a way finance can’t reconcile, you don’t have a pipeline — you have a story generator.

So the real question becomes:

How do we move operational truth into analytical truth without smearing it?

That’s where OLTP vs OLAP and streaming vs batch finally make sense.

OLTP vs OLAP: The Contract, Not the Technology

People talk about OLTP/OLAP like a database debate.

It’s not.

It’s a workload + correctness contract debate.

OLTP systems optimize for:

- fast, concurrent reads/writes

- strict correctness for business operations

- normalized data models, invariants, constraints, transactions

- point lookups (“give me this order”), small updates (“change status”), and strong consistency where needed

If OLTP lies, users feel it immediately.

OLAP systems optimize for:

- scanning lots of data

- aggregations and joins across time (“revenue by cohort by channel”)

- columnar storage, partitioning, denormalization, pre-aggregation

- stable metrics and reproducible reports

If OLAP lies, the company makes the wrong decisions — and you discover it months later.

- Running analytics queries on OLTP: you melt production, and “hot” tables become fragile.

- Running product features on OLAP: you ship latency, inconsistency, and debugging nightmares.

- Trying to keep “one database” for both: you reinvent data pipelines accidentally… usually badly.

The simplest rule:

OLTP is for decisions that affect users now.

OLAP is for decisions that affect the business later.

And then the hard part:

How does data get from one world to the other?

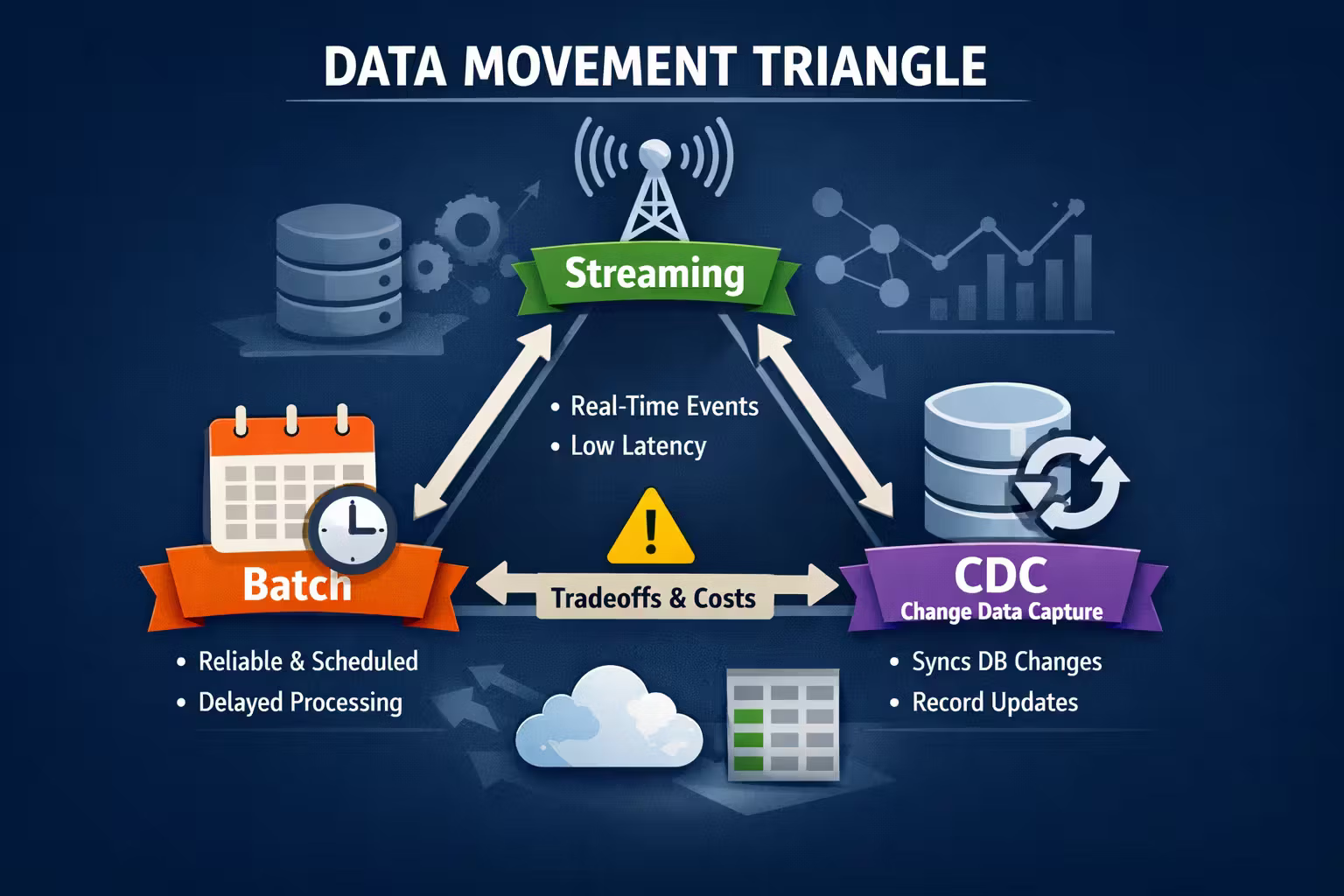

The Data Movement Triangle: Batch, Streaming, CDC

Most teams treat “streaming” like a status symbol.

In practice, you’re choosing between three movement primitives — and each has a cost.

Batch

Cheap and reliable. Great for truth and finance. Bad for “real-time” expectations.

Streaming events

Great for reactivity and pipelines. Harder correctness. Requires schema discipline and backpressure design.

CDC

Copies changes from OLTP. Powerful, but you must understand what you’re capturing: writes, not meaning.

Reality check

You often need two: streaming for immediacy, batch for reconciliation.

Batch: the boring hero

Batch wins when:

- you can tolerate minutes/hours of delay

- you need recomputation and reconciliation

- your definitions are evolving

- you value predictability over novelty

Batch is how finance stays sane.

Streaming: the “now” layer

Streaming wins when:

- you need low-latency signals (fraud, alerts, personalization)

- you want event-driven automation

- you can enforce schema compatibility and idempotency

- you can operate consumer lag, partitions, and retries

Streaming is how operations stay responsive.

CDC: “what changed” without asking developers (but with tradeoffs)

CDC wins when:

- you need to replicate OLTP state into analytical stores

- you want to avoid writing bespoke event emitters everywhere

- you accept that CDC captures database writes, not business meaning

CDC is how replication becomes practical — if you treat it like a sharp tool.

- business events for meaning (streaming)

- CDC for completeness (reconciliation / audit)

- batch for truth repair (backfills and financial close)

The Golden Rule: Don’t Corrupt Production Truth

Production systems need a single place where the truth is committed.

That place is typically your OLTP database — not because it’s cool, but because it is the only thing allowed to say:

“This order exists.”

“This payment was captured.”

“This user is authorized.”

Analytics and pipelines must observe and derive, but they must not mutate the authoritative record.

You have a second product team editing history.

So instead of “writing analytics into production,” we do the opposite:

- treat production state transitions as events

- replicate state outward

- compute metrics downstream

- and reconcile with audit logs when definitions change

That leads to the next core concept: events vs state.

Events vs State: What You Store Changes What You Can Prove

If you only store state (“current status = shipped”), you lose history unless you build history explicitly.

If you store events (“order shipped at t=...”), you can rebuild state and also answer forensic questions.

In practice, you usually need both — but you must understand which is primary in each domain.

State is for serving

Fast reads, current truth, simple queries. But weak forensic capability without history.

Events are for explaining

You can replay, rebuild, audit, and debug. But you must design ordering, idempotency, and schemas.

Publish business events when the change matters to other systems or analysis:

- order_created, order_paid, order_shipped

- subscription_started, subscription_renewed, subscription_canceled

- user_verified, permission_granted

- payout_initiated, payout_failed

Don’t publish “table_updated” — publish meaning.

- emitting events before the transaction commits (“ghost events”)

- unstable schemas (breaking consumers quietly)

- missing idempotency keys (duplicates become bugs)

- no replay strategy (you can’t rebuild downstream truth)

You rarely get global ordering. You get per-entity ordering at best.

Design around:

- a per-entity key (order_id / user_id) to route events

- monotonic version numbers per entity (or timestamps with caveats)

- consumers that tolerate out-of-order and dedupe safely

This month pairs with May’s distributed data reality:

Once data is distributed, correctness is a protocol.

Now we apply that to analytics.

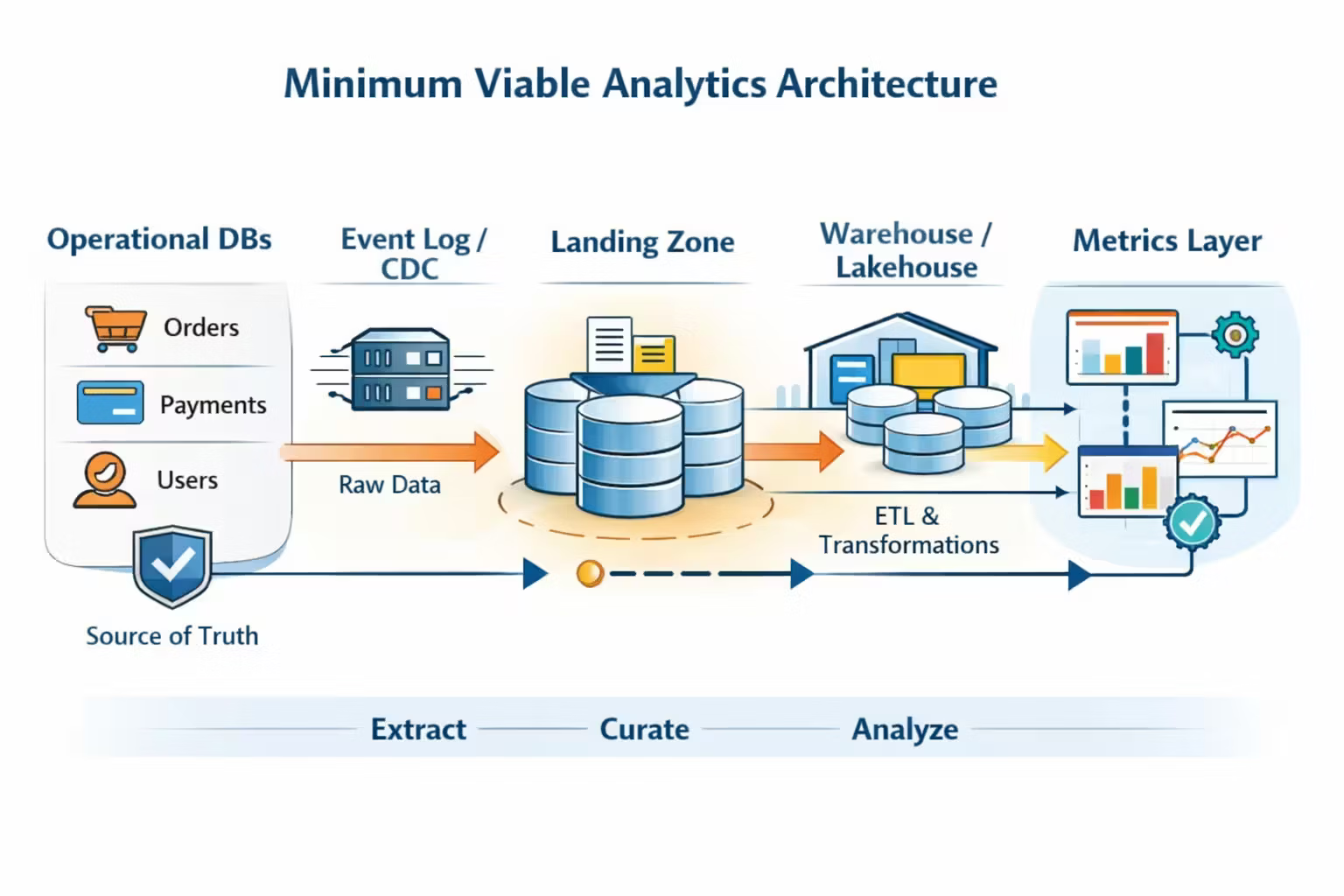

OLTP → OLAP: The Minimum Viable Analytics Architecture

Here’s the smallest architecture that doesn’t lie (and doesn’t melt production).

Establish the sources of truth

Pick the authoritative system for each business concept:

- orders: Order Service / Orders DB

- payments: Payments Provider + internal ledger

- users: Identity store

- inventory: Inventory service

Write it down. Make it boring. Make it explicit.

Extract changes without hurting production

Choose one:

- business events (preferred for meaning)

- CDC (preferred for completeness)

- batch snapshots (preferred for simplicity)

In many teams: events + CDC is the “grown-up” combination.

Land raw data as immutable facts

Create a landing zone (raw tables / raw topics):

- partitioned by time

- never overwritten (append-only when possible)

- with metadata (source, schema version, ingestion time)

Transform into curated models

Build curated tables (clean, typed, consistent):

- dimensional models or wide denormalized marts

- slowly changing dimensions if you need history

- explicit handling for late-arriving data

Add a metrics layer

Define metrics once, not 400 times:

- revenue, active users, churn, conversion

- filters and eligibility

- time windows

- attribution rules

Test and monitor data like software

Data quality checks are not optional:

- freshness

- volume anomalies

- referential integrity expectations

- schema compatibility

- reconciliation checks against ledgers

If you stop here, you already beat most companies.

Because you now have a process that preserves truth boundaries.

“Real-Time” Analytics: What You Actually Mean

Teams say “we need real-time” when they mean one of these:

Fast feedback

Dashboards within minutes. Usually satisfied by micro-batch.

Operational action

Alerts, fraud detection, automation. Needs streaming + reliability.

Product personalization

Recommendations, ranking, adaptive UX. Needs low-latency features + careful correctness.

Experiment readouts

Near-real-time experiment monitoring. Needs exposure logs + attribution discipline.

Micro-batch (every 1–5 minutes) solves “fast feedback” with far less pain than “true streaming.”

Reserve streaming for cases where the business decision actually needs it.

- consumer lag

- backpressure

- retries

- schema compatibility

- replay/backfill

The Metrics Layer: Where Truth Goes to Die (or Survive)

Every org eventually ends up with 17 definitions of “active user.”

That’s not a tooling failure — it’s a governance failure.

The metrics layer is the defense line that stops “analytics entropy.”

What a metrics definition must include

Name and intent

What question it answers. Not just a SQL snippet.

Eligibility rules

Which users/orders count — and why.

Time semantics

Event time vs ingestion time, windows, timezones, late data policy.

Ownership

Someone is accountable for changes. Metrics are products.

Revenue must reconcile with a ledger, and changes must have a paper trail.

A healthy org treats metrics like APIs:

- versioned

- reviewed

- tested

- backward compatible when possible

- with a deprecation story

Which brings us to a topic that looks “data” but is actually “distributed systems”:

schema evolution.

Schema Evolution: Contracts for Data, Not Just APIs

In June we talked about API evolution with consumer-driven contracts.

The same thing applies to data:

- events have consumers

- tables have consumers

- dashboards are consumers

- ML pipelines are consumers

So you need compatibility rules.

- adding optional fields (with sensible defaults)

- adding new event types (without changing old ones)

- adding new tables/views (don’t break existing)

- widening types safely (int → bigint, etc., depending on engine)

- renaming fields without aliases

- changing semantics (“status” meaning changes)

- changing units (cents → dollars) without a contract

- deleting fields or event types

- changing primary keys / identifiers

Adopt a policy like:

- Additive changes anytime

- Breaking changes only with versioning

- Deprecation windows (e.g. 90 days)

- Automated checks in CI (schemas, expectations, sample queries)

- event schemas

- curated tables

- metrics definitions

- semantic models

Streaming Semantics: The 6 Problems You Must Solve

Streaming is not “faster ETL.” It’s a different correctness surface area.

Ordering

You rarely get global order. Design per-entity ordering and tolerate disorder.

Duplicates

“At least once” delivery means duplicates. Idempotency isn’t optional.

Late data

Event time ≠ ingestion time. Decide how long you allow corrections.

Backfills

If you can’t replay, you can’t recover. Plan reprocessing as a feature.

Exactly-once myths

Exactly-once is expensive and contextual. Prefer “effectively once” with dedupe.

Operational load

Consumers lag, partitions skew, and backpressure happens. Streaming is a system to operate.

If that list feels heavy, that’s the point.

Streaming buys time-to-signal. It costs you operational complexity.

Use it like a scalpel.

A Concrete Example: Orders → Revenue Without Lying

Let’s make it real with a common pipeline: e-commerce.

Operational truth: payments and refunds live in a ledger-like model.

Analytical truth: finance wants revenue by day, channel, and cohort.

Observational truth: product wants conversion funnels and drop-offs.

A healthy architecture:

- Order Service writes order state (OLTP)

- Payment Service writes a ledger (OLTP, auditable)

- Publish business events (order_paid, refund_issued, etc.)

- Land events/raw tables immutably

- Curate:

- orders dimension (customer, channel, timestamps)

- payment facts (amount, currency, status)

- refund facts

- Metrics layer defines:

- gross revenue

- net revenue

- recognized revenue rules (if needed)

- Reconciliation job compares:

- metric totals vs ledger totals for each day

- When definitions change:

- backfill curated tables

- bump metric version

- document the change

But you move fast with a protocol: events → curated models → versioned metrics → reconciled truth.

A Decision Matrix You Can Actually Use

When deciding OLTP vs OLAP vs streaming vs batch, don’t start with tools.

Start with questions.

If the answer affects a user immediately, it belongs in OLTP.

Examples:

- “Is this user allowed?”

- “Is this payment captured?”

- “What is the current subscription status?”

Aggregations across time belong in OLAP.

Examples:

- “Revenue by cohort”

- “Conversion rate by channel”

- “Churn by plan over 90 days”

Streaming is justified when the business decision cannot wait for batch:

- fraud/abuse detection

- operational alerts

- near-real-time personalization signals

- low-latency automation

If it’s just dashboards, micro-batch is usually enough.

CDC is best when:

- you need completeness (all writes)

- you want replication with less app code

- you understand your schema and constraints well

But CDC sees writes, not meaning. Use business events to express intent.

Operational Checklist: Data Engineering for Product Teams

This is the “walk into a new system and stabilize it” checklist.

Write down truth boundaries

For each critical business concept:

- authoritative system

- identifier (primary key)

- time semantics (event time)

- reconciliation strategy

Create a raw landing zone

- immutable ingestion

- schema versions captured

- metadata columns (ingested_at, source, partition)

- retention policy (raw is your safety net)

Define curated models

- consistent types and naming

- explicit joins

- history strategy (SCD if needed)

- documentation: what each table means

Establish a metrics layer

- single definitions for key KPIs

- owners and change logs

- semantic naming (not query names)

- deprecation/version policy

Add automated data tests

- freshness checks

- volume anomalies

- uniqueness expectations

- referential expectations

- reconciliation checks (especially money)

Plan for backfills on day one

- replay strategy for events

- backfill jobs that can run safely

- “correctness windows” for late data

Protect production from analytics

- read replicas where needed

- strict query budgets and isolation

- never let OLAP workloads hit OLTP hot paths

If you do these seven steps, you’ve built the foundation for:

- trustworthy dashboards

- safe experimentation

- reliable ML features

- and sane incident response

Resources

The Data Warehouse Toolkit

Dimensional modeling is still one of the best mental models for building curated analytical truth that stays usable.

Change Data Capture (CDC)

A quick overview of the concept: CDC is replication of changes, which is powerful — but captures writes, not meaning.

FAQ

Most product teams should start with: warehouse + disciplined curated models + a metrics layer.

Lakehouse architecture can be great, but it doesn’t solve truth boundaries by itself. If your definitions drift, your lakehouse just stores drift faster.

No. Model meaning as events where it matters, and keep serving state where it’s useful.

A practical rule:

- OLTP serves current state

- events explain transitions

- OLAP derives analytics from a mix of both

Treat metrics like APIs:

- define them centrally (semantic layer / metrics repo)

- assign owners

- require reviews for changes

- version and deprecate

If your org can’t do that socially, no tool will save you.

Querying OLTP directly for analytics until production becomes fragile.

It works… until it doesn’t. Build an extraction path early, even if it’s simple batch snapshots.

What’s Next

This month was about truth boundaries:

- OLTP is where commitments live

- OLAP is where understanding lives

- streaming is where immediacy lives

- and your job is to move truth without corrupting it

Next month is the part architects avoid until the bill arrives:

Cost as a First-Class Constraint

Because systems that scale don’t just break on correctness and latency.

They break on invoices.

Cost as a First-Class Constraint: FinOps for Architects

Reliability is non-negotiable, but “cost” is where architecture meets physics. This month is a practical playbook: how to model cost, allocate it, and design guardrails so your system scales without surprising invoices.

Cloud Infrastructure Without the Fanaticism: IaaS, PaaS, Serverless, Kubernetes

A practical mental model for choosing cloud primitives without ideology—based on responsibility boundaries, scaling, reliability, cost, and team operating capacity.