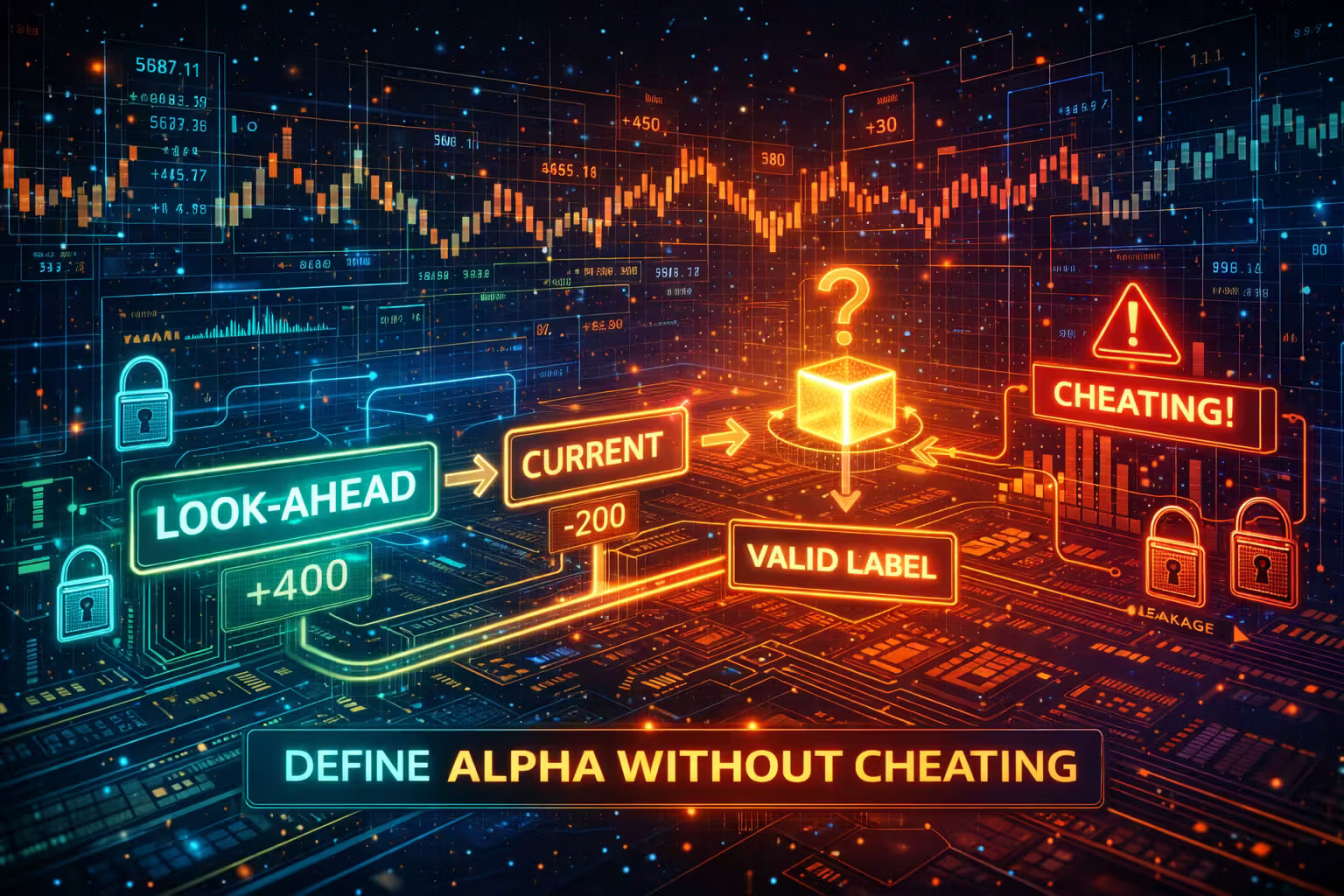

Defining Alpha Without Cheating - Look-Ahead Labels and Leakage Traps

Before I train anything, I need a label that doesn’t smuggle the future into my dataset.

Axel Domingues

In 2018 I learned a painful RL lesson: you don’t get what you want — you get what you reward.

This month I’m realizing supervised learning has the same trap, just wearing a nicer shirt:

- In RL, you accidentally reward the wrong behavior.

- In supervised learning, you accidentally label the future into the present.

Either way, the model looks amazing… until you ask it to do the thing in the real world.

So July is about one boring-sounding decision that will decide whether this entire BitMEX research repo is science or fan fiction:

What does “alpha” mean for my system, and how do I label it without cheating?

What “alpha” means here (and what it doesn’t)

In trading, “alpha” gets used like it’s a magical ingredient. For this project I’m forcing a stricter definition:

Alpha is a predictable edge in the next short window, measurable from information available now.

That definition has two important consequences:

- Alpha is not profit. Profit depends on execution, fees, slippage, and whether BitMEX decides to return 503 in the exact moment you need it.

- Alpha is not a signal you can trade directly. It’s an intermediate target that lets me test whether the order book features I’ve been building actually contain information about near-future price movement.

So the label I want is not “did I make money.”

The label I want is closer to:

“Given the current snapshot, how much did the market move (up or down) in the next X seconds?”

If I can’t predict that reliably, everything downstream (position management RL, maker behavior, sizing) is built on sand.

The contract: snapshot in, movement potential out

Up to now, the repo has been about collecting and cleaning snapshots. Starting this month, the dataset gains a new column that becomes the target for supervised models.

Repo focus:

alpha_detection/produce_alpha_outcome_ahead.pyalpha_detection/utils.py

The key idea in produce_alpha_outcome_ahead.py is a look-ahead label computed from the future best bid/ask.

At each timestamp t, the script looks ahead look_ahead_seconds and asks:

- What was the highest best bid in that future window?

- What was the lowest best ask in that future window?

- Relative to the current best bid/ask, how large was the best up move and best down move?

Then it converts those moves into returns and stores an absolute max alpha label.

That label is not “direction” yet.

It’s “how loud the next minute gets.”

How the look-ahead label is implemented (in this repo)

The script reads a snapshot dataset (HDF5) and writes out a new dataset with alpha columns. In my repo it currently points at Windows-style paths under a train folder and writes a new file prefixed with withAlpha-.

The mechanics matter because they define the exact “no cheating” boundary.

Here’s the heart of the labeling loop (paraphrased to keep it readable):

look_ahead_seconds = 60

for i in range(n_snapshots):

# Base prices at time t

base_bid = best_bid[i]

base_ask = best_ask[i]

# Future window [t, t + look_ahead]

future_bids = best_bid[i:i+look_ahead_seconds]

future_asks = best_ask[i:i+look_ahead_seconds]

# Extreme future prices

max_future_bid = future_bids.max()

min_future_ask = future_asks.min()

# Returns (relative movement potential)

max_return = (max_future_bid - base_ask) / base_ask

min_return = (min_future_ask - base_bid) / base_bid

# Alpha is the larger magnitude move

abs_alpha = max(abs(max_return), abs(min_return))

# Store + mark validity

A few “engineering” notes about what’s actually happening:

- The up move uses

base_askas the reference. That’s deliberate: if you want to buy now, you pay the ask. So “how far can price run up from what I’d pay?” anchors on the ask. - The down move uses

base_bidas the reference. Similarly: if you sell now, you hit the bid. - Using the extremes in the future window makes this a “best case move” measure. It’s not saying we actually captured it.

This is why I call it a movement potential label.

The valid flag (aka: don’t teach the model with broken examples)

There’s a second column the script writes that I treat as non-negotiable: a validity mask.

The end of the dataset can’t be labeled properly because it doesn’t have a full look-ahead window.

Instead of faking it, the script sets valid[i] = 0 when i + look_ahead_seconds runs past the end, and only produces alpha values for examples that have the full future horizon.

Why “look-ahead labels” are a leakage minefield

Defining a label based on the future is normal.

Using future information in the features is the cheat.

The problem is that dataset pipelines make it very easy to leak without noticing. Here are the leakage traps I’m explicitly guarding against before I run a single supervised baseline.

Leakage trap 1: random train/test splits

If you shuffle examples randomly, you leak by proximity.

A look-ahead label means adjacent timestamps share future windows. If you split randomly, your train set and test set will share overlapping windows of the same market move.

Fix: split by time (contiguous blocks). Hold out entire days/weeks/months.

Leakage trap 2: centered rolling features

If you compute rolling features with a centered window (or any symmetric smoothing), the feature at time t includes information from t+1, t+2, etc.

Fix: rolling windows must be causal (only past). If it’s not strictly “using history up to now,” it’s suspect.

Leakage trap 3: normalization computed on the full dataset

I just wrote a whole post about this in June.

If you compute mean/sigma across the full dataset (including the future), you leak future distribution information into every feature.

Fix: compute normalization parameters on the training slice only; persist them; reuse for validation/test/inference.

Leakage trap 4: “future information by timestamp mismatch”

If your snapshot timestamps drift or you merge data sources incorrectly, you can end up using a trade that happened after the snapshot as if it happened before.

That’s leakage disguised as a join bug.

Fix: treat timestamps as first-class data. Validate monotonicity. Track drift. Refuse to merge if clocks disagree.

Leakage trap 5: label definition that assumes fills

The label uses best bid/ask extremes, not actual fills.

That’s okay as a movement label, but it becomes a cheat if I later interpret it as “profit opportunity captured.”

Fix: keep the label honest: it’s “movement potential,” not “PnL.”

The “don’t lie to yourself” checklist for alpha labels

Before I trust this label, I run checks that are deliberately boring.

If any check fails, I don’t tune a model. I fix the pipeline.

Check 1: validity coverage

- What percent of rows are

valid == 1? - Is the invalid region only the tail (exactly the look-ahead horizon length)?

If invalid shows up in the middle, I have missing time or collector gaps.

Check 2: alpha distribution sanity

- Is alpha mostly near zero (as expected for quiet periods)?

- Are there fat tails (as expected for crypto)?

- Are there impossible values (negative alpha, NaNs, infinities)?

Check 3: alpha vs spread

- In very wide spreads, does alpha look inflated?

If so, I might be measuring spread noise instead of movement.

Check 4: time split leakage test

Train a dumb baseline (even a linear model) on one time block, evaluate on a future block.

If performance collapses to random, either:

- the signal is genuinely weak (possible), or

- I accidentally built a label/feature mismatch (very possible).

Check 5: “shift test”

Shift features forward by one step and re-train.

If accuracy stays the same, I’m almost certainly leaking the future.

Where this fits in the repo (and why alpha_detection/utils.py exists)

The alpha labeling script is intentionally simple: read snapshots, compute labels, write a new HDF5 file.

The alpha_detection/utils.py module looks like it’s “out of place” at first glance because it contains TensorFlow helpers (sampling, entropy, orthogonal init, conv/fc layers, an LSTM implementation).

What it signals is where I’m going next:

- I’m not planning to stop at linear baselines.

- I’m going to build deep models for representation learning, and I want a small utility layer that matches the rest of my 2019-era TensorFlow tooling.

So July is the bridge:

the dataset now has a target, and the codebase has the primitives to start learning it.

Resources I’m using this month

What changed in my thinking

I used to treat labels as “boring plumbing.”

Now I see them as the real objective function of the whole project. If the label is wrong (or leaky), the model is not learning microstructure. It’s learning my mistakes.

FAQ

It’s a starting point that’s long enough to contain real microstructure events (liquidity pulls, bursts) but short enough that the order book still matters. I expect to sweep this later and see how stability changes with horizon.

Direction is the next problem (and it’s harder). This label is asking a simpler question: “will the next window be quiet or loud?” If I can’t predict loudness, I don’t trust any directional model built on these features.

A label is allowed to use the future — that’s literally what we’re predicting. Cheating happens when the input features also contain future information (via smoothing, normalization, joins, or splitting mistakes).

I avoid random splits and I evaluate on future blocks (walk-forward style). With overlapping horizons, time splits are not “nice to have,” they’re required.

What’s next

Now that the dataset has a target, I can finally do the thing everyone wants to do first: train a model.

Next month is intentionally humbling.

I’ll start with simple models, time-based validation, and the first plots that tell me whether these microstructure features actually contain signal… or whether I’ve been building an expensive noise machine.

Supervised Baselines - First Alpha Models, First Humbling Curves

I train my first alpha predictor on BitMEX order-book features, and learn why ‘it trains’ is not the same as ‘it works’.

Normalization Is a Deployment Problem - Mean/Sigma and Index Diff

In June 2019 I stop treating feature scaling as “preprocessing” and start treating it as part of the production contract - same transforms, same stats, same order — or the live system lies.