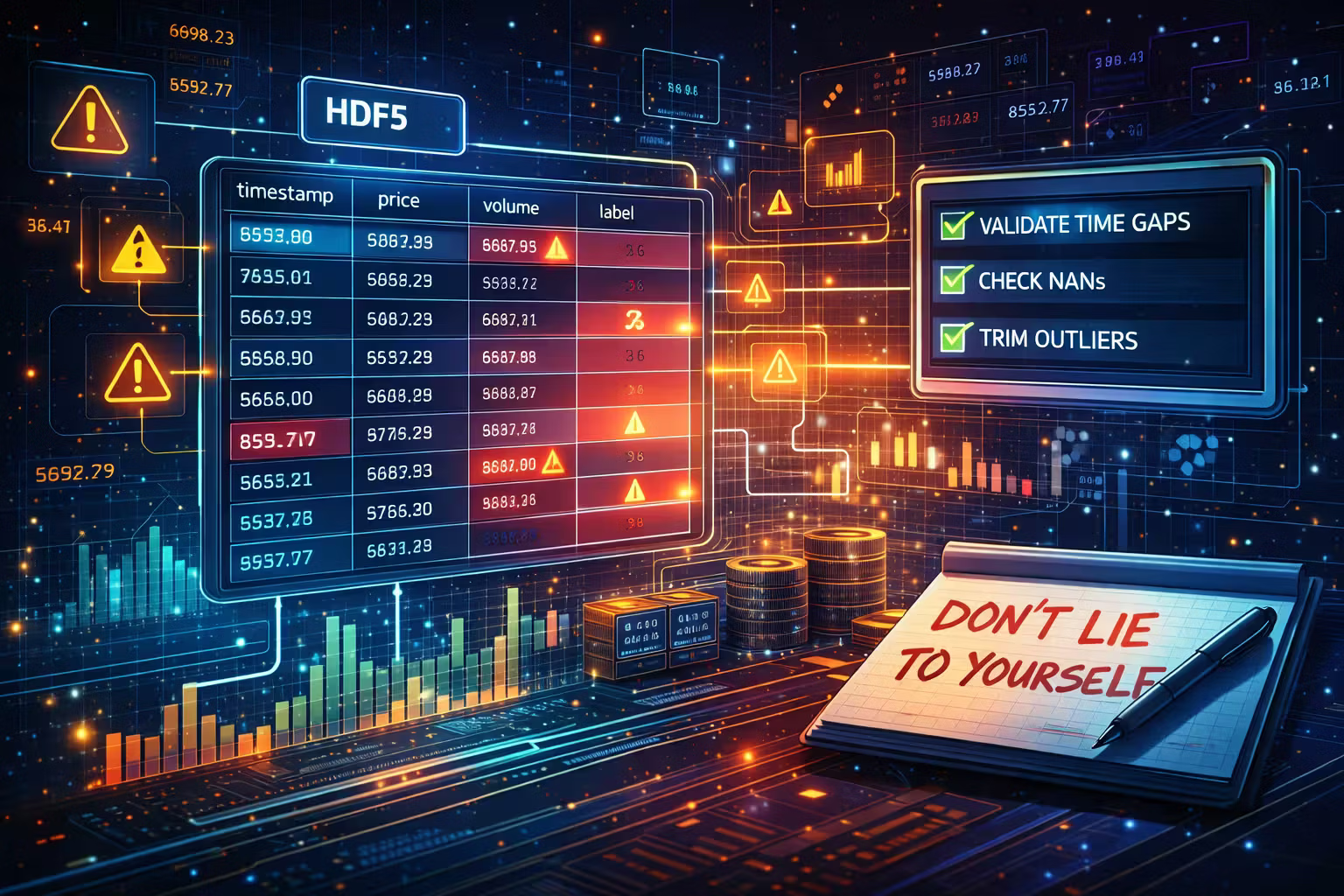

Dataset Reality — HDF5 Schema, Missing Data, and “Don’t Lie to Yourself” Rules

In April 2019 I learned that the hardest part of trading ML isn’t the model — it’s the dataset contract. This month is about HDF5, integrity checks, and building rules that stop “good backtests” from lying.

Axel Domingues

Last month I finally had the collector running.

Websocket stream connected. Snapshots flowing. Logs printing something that looked like “market data”.

And then I did the most dangerous thing you can do next:

I opened the dataset.

It’s a humbling moment because your code can be “correct” and your data can still be wrong in a thousand tiny ways:

- gaps that look like flat markets

- duplicates that look like stability

- time drift that looks like prediction power

- partial snapshots that look like “strong signals”

This month is the transition from “I can collect data” to “I can trust the data enough to train on it.”

What you’ll get

A practical mental model for the dataset as a contract between the market and my models.

The HDF5 shape

How my collector writes daily HDF5 snapshot files (and why I keep the schema boring on purpose).

Missing-data playbook

Concrete failure modes (gaps, duplicates, partial books) and the first checks I added to catch them.

“Don’t lie” rules

The checklist I follow so I don’t turn dirty data into fake alpha.

The dataset is not “storage” — it’s the contract

In 2018 RL, I learned something that carries over perfectly:

If your environment is wrong, the agent learns the wrong game.

In trading, the dataset is the environment. If the dataset lies, your backtest becomes a story generator.

So I started treating my dataset as a contract:

- What time means (exchange time vs local time)

- What a snapshot means (full book? partial? L2 vs L3?)

- What “no event” means (stable market vs missing packets)

- What labels mean (future information leakage is a silent killer)

This is why I’m writing this post before doing alpha labels and models. If I don’t get this right, everything after becomes theatre.

Why HDF5 (and what I’m storing per day)

I chose HDF5 because I wanted:

- one file per day, per instrument

- fast read/write from pandas (because I’m going to rerun audits constantly)

- a structured container (not “CSV soup”)

- something I could version and migrate as the schema changes

In the repo, the daily output pipeline lives in:

BitmexPythonDataCollector/SnapshotManager.py

The write path in my early version looks like this (directly grounded in the code):

file_name = self.contract_symbol + self.last_processed_ss_ts.strftime("-data-%d-%m-%Y.h5")

self.snapshots_to_save.to_hdf(file_name, key="df", mode="w")

So a real file name is:

XBTUSD-data-30-05-2019.h5

And the dataset inside uses a single key:

key="df"

That decision (one daily file + one key) pays off later because it makes every downstream script predictable.

This month isn’t “fix everything month”. This month is make the risks explicit and add integrity checks that detect damage.That means a crash can lose an in-memory buffer.

Snapshot schema: think in “feature families”, not a long column list

At first, I wanted all the columns.

That was a mistake.

What I actually needed was structure: groups of features that come from the same microstructure idea.

You can see this perspective show up later in the code when I group features into families (for “deep silos” style models). But the idea starts here: I want the dataset to have a shape that matches how I reason about the book.

These are representative column groups produced by the snapshot pipeline (see BitmexPythonDataCollector/SnapshotManager.py).

- Meta / time

timestamp(local snapshot timestamp)seconds_last_move(time since last best bid/ask movement)

- Top-of-book / price

best_bid,best_askmid_price,spreadacc_price_change(running price change from a base reference)

- Traded volume (by side)

buy_traded_volume,sell_traded_volumebuy_traded_volume_15,sell_traded_volume_15

- Liquidity created / removed

bid_liquidity_creation,ask_liquidity_creationbid_liquidity_creation_15,ask_liquidity_creation_15- per-window / per-level variants for “where the pressure is happening”

- Order book structure (depth window)

bid_sizes_0..N,ask_sizes_0..N(size by quote level)bid_steps_0..N,ask_steps_0..N(distance from best quotes)

- Label-like field (used later)

moved_up(-1 down, 0 no move, 1 up)

The exact set evolves, but the families stay stable.

The win of thinking this way:

- I can debug each family independently

- I can normalize each family independently

- I can build model architectures that respect the structure (instead of a giant flat vector)

That becomes critical later.

Missing data is not one problem — it’s a zoo

Once I had a few daily files, the problems showed up quickly.

1) Gaps: “flat market” vs “silent failure”

A gap in timestamps can mean:

- the market was quiet

- the websocket stalled

- my loop was blocked by something I didn’t notice

- my machine clock drifted

- BitMEX throttled me and I didn’t handle it cleanly

If you don’t distinguish these, your model will happily treat missing data as stability.

2) Duplicates: fake certainty

Duplicates happen when reconnect logic replays state, or when I append without realizing I already saw this snapshot.

Duplicates make learning curves look smoother than they should. That’s how you get “great training loss” and “dead reality”.

3) Partial snapshots: the book that never existed

The nastiest bug class is when the book is internally inconsistent:

- bids/asks arrays mismatched lengths

best_bid >= best_ask(crossed book)- missing depth levels

- negative or zero sizes (parsing or merge bugs)

A model trained on that learns a book that never existed.

But in trading, dataset errors often correlate with high-volatility periods — which means you can accidentally learn “collector failure modes” as if they were alpha.They show the model. They don’t show the dataset audit.

The “Don’t Lie To Yourself” rules

These are the rules I wrote for myself before doing any labeling or modeling.

They’re not theoretical. They’re how I prevent myself from writing impressive posts about fake performance.

Rule 1: Timestamp sanity is mandatory

Checks I run on every daily file:

- timestamps are monotonic increasing

- no “teleport” gaps beyond a threshold (I log a histogram of gap sizes)

- no negative deltas (out-of-order inserts)

Rule 2: The book must be internally consistent

At minimum, per snapshot:

best_bid < best_ask- depth arrays match expected lengths

- sizes are non-negative

- spreads are within plausible ranges

Rule 3: Missing data is a first-class label

I add explicit flags or drop windows:

- reconnect windows

- stalls

- known bad time ranges

If I can’t explain a region, I don’t train on it.

Rule 4: I never trust “good backtests” without data audits

Before any model:

- print basic stats per feature family

- verify distributions don’t shift wildly due to bugs

- run small visual spot checks on random windows

Rule 5: Dataset versions are real versions

If I change schema or fix logic:

- I write a migration script

- I bump the dataset version

- I don’t mix versions in training

Instrumentation is the difference between research and fiction.

A tiny integrity script I keep rerunning

I didn’t want a huge pipeline yet. I wanted a small script that tells me: is this day safe to use?

Because the files are HDF5 with key="df", the skeleton looks like this:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_hdf("XBTUSD-data-30-05-2019.h5", key="df")

# 1) time sanity

s = pd.to_datetime(df["timestamp"], errors="coerce")

deltas = s.diff().dt.total_seconds()

print("max gap seconds:", deltas.max())

print("negative gaps:", int((deltas < 0).sum()))

print("null timestamps:", int(s.isna().sum()))

# 2) book sanity

bad_spread = int((df["best_bid"] >= df["best_ask"]).sum())

print("bad spreads:", bad_spread)

# 3) duplicates

if "timestamp" in df.columns:

dupes = int(df.duplicated(subset=["timestamp"]).sum())

print("timestamp duplicates:", dupes)

It’s not glamorous, but it catches the worst lies fast.

What changed in my thinking (April takeaway)

In 2017–2018 I learned that training stability is engineering.

In April 2019 I learned a sharper version:

Data stability is engineering — and it comes before the model.

I used to treat “dataset creation” as plumbing.

Now I treat it as part of the research method.

Resources (the stuff I’m actually using)

FAQ

CSV is too easy to corrupt and too slow for repeated reads. Parquet is great, but my priority was: “works with pandas, simple daily files, easy versioning.” HDF5 gave me that fast.

Yes — because models treat missingness as a pattern. If missingness correlates with volatility (and it often does), you can accidentally learn “collector bugs” instead of market structure.

Monotonic timestamps + gap histogram. It’s the fastest way to spot stalls, reconnect damage, and replay behavior.

What’s next

Now that I can at least detect lies, I can start asking a better question:

What features actually encode microstructure behavior?

Next month I’m focusing on liquidity created vs removed — the push/pull of the order book — and why those features feel closer to how real participants move the market.

Feature Engineering, But Make It Microstructure: Liquidity Created/Removed

If the order book is the battlefield, features are the sensors. This month I stop hand-waving and teach my pipeline to measure liquidity being added and removed - in a way I can deploy live.

The Collector - Websockets, Clock Drift, and the First Clean Snapshot

In March 2019 I stop “talking about microstructure” and start collecting it. Websockets drop messages, clocks drift, and the only thing that matters is producing a snapshot I can trust.