Continuous Control - DDPG and the Seduction of Off-Policy

This month I left “toy” discrete actions and stepped into continuous control. DDPG looked like the perfect deal—until I learned what off-policy really costs.

Axel Domingues

In deep learning, instability usually feels like a bug you can corner: gradients explode, activations saturate, initialization is off.

In reinforcement learning, instability is often the default state of the system.

This month I crossed a threshold: continuous control.

No more “left / right.” Now the agent outputs real-valued actions—torques, forces, steering angles—things that feel closer to robotics than videogames.

And that’s where I met the seduction:

Off-policy learning looks like free efficiency.

You can reuse old experience. You can learn from a replay buffer. You can pretend data is “just data.”

DDPG promises exactly that.

In plain English: an actor-critic method for continuous actions, where the actor outputs a real-valued action directly (deterministic), and a critic learns to judge it.

And then it reminds you: in RL, your data is you.

The moment RL started to feel… physical

With discrete environments, I could sometimes forgive myself for hand-waving:

- the action space is tiny

- exploration is obvious

- “random actions” still kind of make sense

With continuous actions, exploration becomes an engineering question:

- How do you explore without instantly crashing?

- How do you keep the policy from saturating to nonsense outputs?

- How do you know whether failure is “bad algorithm” or “bad action scaling”?

This is where RL stops feeling like a chapter of ML and starts feeling like control systems wearing a neural network mask.

What I’m trying to learn this month

I’m not chasing “solves MuJoCo” this early.

I’m trying to build a working mental model for why continuous control is different, and why off-policy is both powerful and fragile.

My learning goals

Continuous actions

What changes when actions are real-valued (and exploration can crash you).

Deterministic actor-critic

Actor outputs actions. Critic judges them.

How the two co-evolve (and mislead each other).

Off-policy costs

Replay buffers feel like “free efficiency” until distribution mismatch shows up.

Debugging truth

Diagnostics that reveal drift: action stats, Q-scale, buffer health, silent failure.

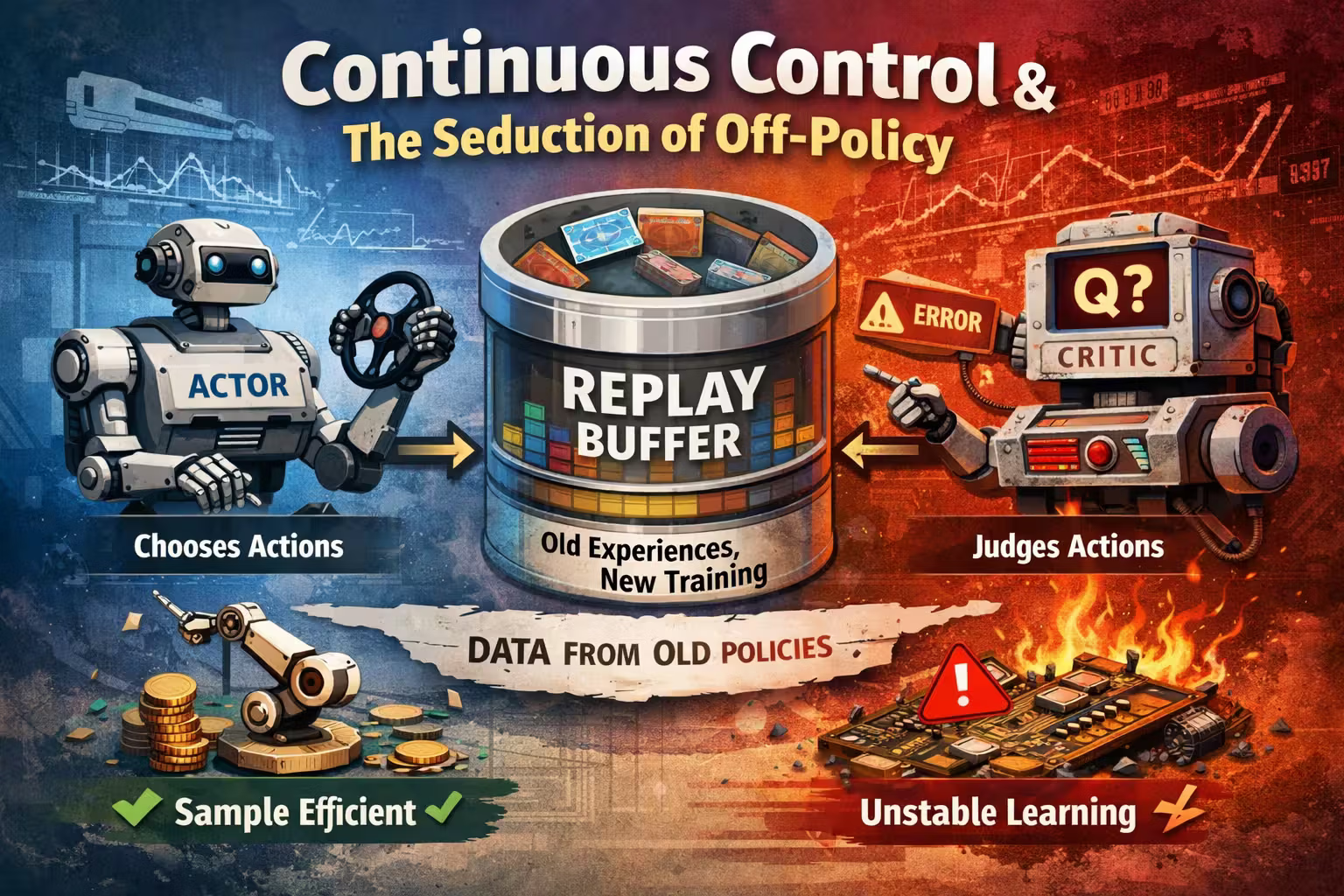

The cast of characters (plain English)

Actor

Outputs the action directly (continuous control).

Critic

Scores how good an action is in a state (and can hallucinate).

Replay buffer

Stores old transitions so you can train many times.

Target networks

Slow-moving copies that reduce the “moving target” problem.

Here’s the mental picture that finally made DDPG click:

- The actor is a function that outputs an action.

- The critic is a function that judges how good an action is in a state.

- The actor improves by trying to choose actions the critic says are good.

- The critic improves by learning from transitions and “bootstrapping” future value.

And the replay buffer is the “memory” that feeds training.

Which sounds stable… until you remember:

- the actor is changing

- the critic is changing

- the data distribution is changing

- and your target is partly computed from your own predictions

This month felt like building a machine that’s assembled out of parts that are still melting.

Why DDPG feels so attractive (and why it’s dangerous)

Off-policy has a very tempting story:

- “Collect experience once.”

- “Train many times.”

- “Be sample efficient.”

But off-policy isn’t a free lunch. It’s a loan.

Your replay buffer contains experience from older policies.

So the critic is trained on data that doesn’t match the actor’s current behavior. If the mismatch grows, the critic can become confident about situations the current actor never actually visits.

You borrow stability now… and repay it later with complexity:

- distribution mismatch

- replay buffer bias

- target networks

- exploration noise tuning

- sensitivity to scale

- critic overestimation

- training collapse that looks random

The engineering questions I keep running into

1) What does exploration even mean here?

In continuous control, random actions can be catastrophically bad. So exploration becomes noise design:

- how much noise?

- how long?

- applied to actions or parameters?

- does noise destroy stability?

And the annoying part: “more exploration” can make training look worse for a long time.

2) Is the critic learning reality or hallucinating it?

The critic is supposed to estimate “how good an action is.”

But since it bootstraps its own predictions, it can start believing a fantasy world where:

- some actions are amazing

- the actor chases them

- and the real environment disagrees violently

3) Am I learning a policy… or learning a scaling bug?

Continuous actions introduce a subtle new class of error:

- action bounds

- normalization

- reward scale

- observation scale

A bad scale doesn’t look like a crash.

It looks like “training is unstable.”

What I’m watching (my debugging dashboard)

This month I started treating RL runs like production systems with a monitoring suite.

Here’s what I care about.

Reward curve (but with suspicion)

I watch average episode return, but I don’t trust it alone. Spikes can be luck; plateaus can hide improvement.

Critic loss + Q magnitude

If the critic loss explodes or Q-values drift to absurd magnitudes, the agent is learning a story, not a policy.

Action stats

Mean, std, clipping rate. If actions saturate at bounds early, the actor is stuck in “panic mode.”

Replay buffer sanity

What’s the distribution of rewards in the buffer? Is it dominated by failure? Is it too stale?

And because I’m coming from deep learning, I also keep an eye on:

- gradient norms when things “suddenly die”

- advantage-like signals (even though DDPG doesn’t use advantage directly)

- whether updates are dominated by a tiny subset of transitions

- Reward up is not proof.

- Q-values sane is a prerequisite.

- Actions saturating is usually a dead run.

- Buffer dominated by failure means the agent is learning to fail efficiently.

The common failure modes (what I expect to break)

This month had fewer “clean lessons” and more recognizable failure shapes.

Here are the ones that stood out:

What it looks like: Q-values drift upward until nothing is grounded.

Likely cause: critic bootstrapping + distribution mismatch.

First check: Q min/mean/max + critic loss spikes.

What it looks like: nearly constant actions, saturating at bounds.

Likely cause: critic gives misleading gradients or action scaling is off.

First check: action mean/std + clipping rate + bounds.

What it looks like: reward climbs, then collapses and never recovers.

Likely cause: one destabilizing update or critic drift.

First check: value scale shift + action saturation + buffer staleness.

What it looks like: training becomes “learning to fail consistently.”

Likely cause: early experience dominates; not enough recovery data.

First check: reward distribution in buffer + age of samples.

What it looks like: too slow → stalls; too fast → instability.

Likely cause: target updates not tuned to environment dynamics.

First check: correlate performance changes with target update settings.

What it looks like: small scaling change flips “works” ↔ “dead.”

Likely cause: gradients become too large/small; critic becomes brittle.

First check: normalize observations; verify action ranges; sanity-check reward scale.

What it looks like: reward improves but behavior isn’t real control.

Likely cause: reward design exploit.

First check: short rollouts; verify the agent is doing the intended behavior.

It’s “it learns something… but not the thing you think.”

Field notes (what surprised me)

Off-policy isn’t “more efficient,” it’s “more conditional”

I expected replay buffers to make training smoother.

Instead, they made training more sensitive:

- to the quality of early experience

- to how exploration noise behaves

- to whether the critic is grounded

Off-policy feels like: “I can train more.”

In practice it feels like: “I can train more, and also be wrong more.”

Continuous control punishes sloppy interfaces

This ties back to January’s theme: learning is an interface problem.

In continuous control, the interface is everywhere:

- observation scaling

- action bounds

- reward scale

- termination conditions

- timestep size

Small interface mistakes don’t throw exceptions.

They produce policies that “kind of move” and never improve.

The critic is the fragile heart

DDPG’s critic is powerful, but it’s also the component most likely to drift into fiction.

When DDPG breaks, it often breaks there first.

September takeaway

Off-policy is not “more efficient.”

It’s more conditional — it works only when your data and your policy stay aligned.

The fragile heart

When DDPG breaks, it usually breaks in the critic first.

So I treat critic sanity as my earliest warning light.

What’s next

Next month I want to tackle a different kind of instability.

DDPG showed me how fragile learning becomes when:

- you bootstrap

- you approximate

- and you reuse off-policy experience

Now I want to study the opposite design philosophy:

What if we keep updates “trustworthy” by limiting how far the policy can move?

That’s where TRPO enters as the idea, and PPO/PPO2 enter as the engineering version I can actually run.

If September was “continuous control is seductive,”

October will be: “stability is a feature you have to design.”

Stability is a Feature You Have to Design

After DDPG, I stopped thinking of RL instability as a surprise and started treating it like a design constraint. This month I learned why TRPO exists — and why PPO/PPO2 became the practical answer.

Why RL Training Is Unstable (A Catalog of Breakage)

After actor-critic finally felt “trainable,” I hit the next wall - RL doesn’t just fail—it fails in loops. This month is my map of the most common ways it breaks.