Caching Without Folklore: Redis, CDNs, and the Two Hard Things

Caching is not “make it faster.” It’s a contract: what can be stale, for how long, for whom, and how you recover when it lies. This month is a practical architecture guide to caching layers that scale without corrupting truth.

Axel Domingues

Caching is the oldest performance trick in software.

It’s also one of the fastest ways to ship silent correctness bugs.

By October 2021 I’ve seen the same failure pattern over and over:

- “We added Redis and the latency went down.” ✅

- “Then weird things happened.” 😐

- “We spent six months chasing ghosts.” ❌

The ghosts are always the same:

- cache keys that don’t match the real variability (user, locale, permissions)

- staleness that wasn’t explicitly allowed, but happened anyway

- “invalidate on update” workflows that miss edge cases

- stampedes at peak traffic, right when you needed the cache most

This post is about replacing folklore with a mental model you can design, operate, and defend.

The promise

Lower latency and higher throughput without breaking correctness.

The risk

Stale or cross-user data leaks that look like “random bugs”.

The real skill

Choosing what can be cached and what invariants must never be cached.

The outcome

A cache design that is observable, bounded, and recoverable.

The Only Two Questions That Matter

People joke about “the two hard things”:

- naming things

- cache invalidation

- off-by-one errors

Funny because it’s true — but also misleading.

The real two hard things (architecturally) are:

- Defining truth vs performance (what is allowed to be stale?)

- Proving your cache keys match reality (who sees what, and why)

If you get those right, invalidation becomes a manageable engineering problem.

If you get those wrong, your cache becomes a bug amplifier.

If your policy is implicit, your bugs are implicit too.

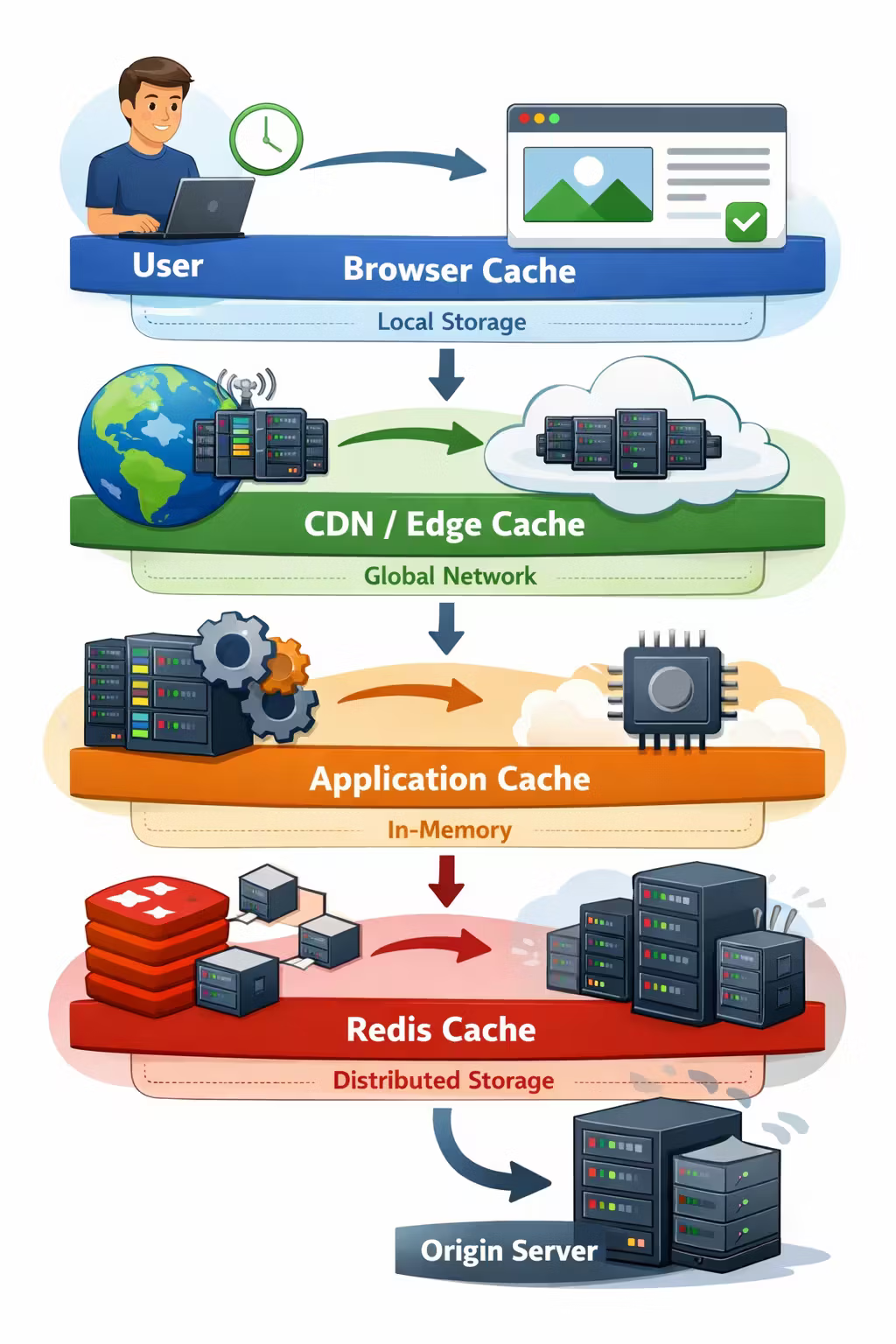

A Practical Taxonomy: The 4 Caches You Already Have

Before Redis or CDNs, you already have caching behavior:

Browser cache

Great for static assets and safe GETs. Dangerous when personalized data isn’t keyed correctly.

CDN / edge cache

Eliminates geographic latency. Requires explicit cache-control and correct variation (“Vary” is your friend).

App / server memory

Fastest cache. Least shareable. Resets on deploy. Great for small hot sets and computed config.

Distributed cache (Redis, Memcached)

Shared across instances. Powerful. Also the easiest place to accidentally store “truth” with no guardrails.

A useful architectural stance:

Treat caching as a stack of contracts, not a single technology.

A Mental Model That Scales: Caches Store Answers, Not Truth

Databases store truth (as best as we can make it).

Caches store answers we’re willing to re-derive.

That sounds obvious, but teams constantly violate it by accident.

Here’s the simple rule:

That’s why these usually are safe to cache:

- static assets (immutable by content hash)

- read-only reference data (countries, currencies)

- computed views with acceptable staleness (leaderboards, dashboards)

- “read-your-write not required” public pages (home page, marketing)

And these are usually not safe to cache without extra design:

- permission-filtered data (who can see what?)

- money state (balance, credits, inventory)

- anything that must reflect a recent write (checkout, booking, seat selection)

- anything that varies by “hidden” dimensions (A/B tests, locale, device class)

Cache Key Design: “What Varies?” Is the Real Question

Most cache incidents are not “Redis failed.”

They’re key design failures.

A good cache key includes every dimension that changes the answer.

The key dimensions checklist

Include the things that change data visibility:

- user id (or “anonymous”)

- tenant / org id

- roles or permission version (not raw roles if they’re huge)

- feature flag cohort (only if it changes the response)

Include the things that change how the response is shaped:

- locale / currency

- device class (mobile vs desktop) if the payload differs

- API version

- query params that affect filtering/sorting/paging

Include the things that change what “fresh” means:

- “as of” timestamp buckets (if you do time-window caching)

- data version / entity updated_at (for conditional caching patterns)

If you can’t prove the cached value can be shared across users, don’t share it. Prefer per-user keys until proven otherwise.

Browser + HTTP Caching: You Get a Free CDN If You Tell the Truth

If you do nothing, browsers and CDNs will still make decisions.

If you want reliability, you need to own the semantics.

The minimum viable HTTP caching posture

- Use Cache-Control intentionally (not by accident)

- Know the difference between public and private

- Use ETag or Last-Modified for conditional revalidation where appropriate

- Use Vary when the same URL can legitimately produce different representations

A safe default split

Static assets (JS/CSS/images built assets)

- immutable naming (content hash)

- long cache TTL

- “cache forever” is correct because the URL changes

HTML / API responses

- conservative TTLs

- explicit “private” where user-specific

- revalidate when uncertain

CDN Caching: The “Vary” Tax and the “Purge” Trap

CDNs are incredible when you can keep the rules simple:

- static assets are easy (immutable URLs)

- public pages are easy-ish

- personalized pages are hard

The “Vary” tax

The more dimensions your response varies on (cookies, headers, locale), the less effective shared caching becomes.

That’s not a failure — it’s reality.

Your architecture choice is:

- reduce variation (move personalization client-side or edge-side)

- or accept lower cache hit ratio and focus on backend efficiency

The “purge” trap

Teams love “just purge on update.”

It works… until it doesn’t.

Because:

- updates are not centralized

- purges fail

- purges can be too broad (thundering herds)

- purges can be too narrow (stale pockets)

Preferred pattern: use immutable URLs for assets and bounded TTLs for content, and treat purging as an optimization, not correctness.

Redis Caching Patterns: Pick the One That Matches Your Failure Modes

Redis is not one thing — it’s a toolbox.

Here are the patterns that matter for system design:

Cache-aside (lazy loading)

App checks cache → on miss fetch DB → populate cache. Simple. Miss storms are your main risk.

Read-through

Cache layer fetches on miss. Centralizes policy but can hide complexity if you’re not careful.

Write-through

Write goes to cache + DB together. Good for read-heavy keys. Adds write latency and coupling.

Write-behind (dangerous)

Writes land in cache and flush later. Great for throughput; terrifying for correctness. Use only with explicit invariants.

My bias in 2021 production systems:

- start with cache-aside

- add stampede protection

- only move to write-through for narrow, proven hotspots

The Two Failure Modes That Kill You in Production

1) Cache stampede (dogpile)

The cache expires.

A thousand requests arrive.

All of them miss.

All of them hammer the DB.

Congratulations: your cache caused your outage.

Defenses that actually work:

- single-flight / request coalescing (only one recompute per key)

- soft TTL + stale-while-revalidate (serve slightly stale, refresh in background)

- jitter TTLs (avoid synchronized expirations)

- rate-limited rewarm (especially after deploy)

2) Cache poisoning (wrong answers stored)

Not security-poisoning (though that exists too).

I mean “we cached an answer under the wrong key” — and now everyone sees it.

Root causes:

- forgot a variability dimension

- key collisions

- caching error responses

- caching partial data during downstream failures

Defenses:

- strict key naming conventions

- “do not cache” for 4xx/5xx by default

- separate namespaces per environment and per version

- include a schema/version suffix in keys

TTLs Are Not Correctness. TTLs Are Damage Control.

TTL is a bounded lie.

Sometimes that’s exactly what you want.

But TTL doesn’t answer:

- who is allowed to see stale data?

- what kind of stale data is acceptable?

- what happens when the cache is wrong?

So treat TTL as one knob, not “the strategy.”

A realistic TTL strategy

- hot, safe data: longer TTLs (minutes to hours)

- semi-dynamic data: short TTLs + revalidation

- riskful data: cache only with explicit versioning or don’t cache

Designing Cache Invalidation Without Losing Your Soul

Cache invalidation becomes manageable when you do one of these:

- Make URLs/keys immutable (versioned by content hash or entity version)

- Bound staleness (short TTL + revalidate)

- Centralize writes so invalidation can be reliably triggered

- Accept eventual consistency explicitly in UX (show “updated a moment ago”)

Three practical invalidation strategies

Key includes a version:

user:123:profile:v42product:sku123:details:updatedAt:2021-10-12T10:03Z

When the entity changes, the key changes. No purge required. Old keys die by TTL.

When a write succeeds, publish an event (or enqueue a job) that invalidates affected keys.

This is operationally harder than it sounds:

- you need retries

- you need idempotency (next month…)

- you need a mapping from entity changes → cache keys

Use TTLs that bound harm and revalidate with conditional GET / background refresh. Correctness is achieved by bounded staleness, not perfect invalidation.

The “Boring Stack” for Caching (That Actually Scales)

The goal is not the fanciest cache.

The goal is predictable behavior under load.

Here’s the stack I trust in most product systems:

Static assets

Content-hashed filenames + long-lived browser/CDN caching.

Public GET endpoints

CDN caching with conservative TTLs + “Vary” only where necessary.

Personalized data

Private caching at the browser (sometimes) and per-user caching at Redis (when safe).

Hot computed views

Redis cache-aside + stampede control + short TTLs + metrics.

This is “boring” because it avoids cleverness that’s hard to operate.

The Observability You Need (Or Your Cache Will Lie Quietly)

You cannot operate caching by vibes.

You need metrics that tell you when it’s helping and when it’s hurting.

Minimum cache dashboard

- hit ratio (overall + per key family)

- p50/p95 latency with and without cache hits

- backend request rate (DB/QPS) correlated with cache misses

- error rate by layer (CDN, app, Redis, DB)

- stampede indicators (spikes in miss rate + DB load)

Logging that pays off

- log cache key family (not full keys if sensitive)

- log cache action (HIT/MISS/STALE/REFRESH)

- log TTL chosen (so you can reason about policy drift)

A Step-by-Step Cache Design Review (Use This in PRs)

Declare what you’re caching (and why)

Write it down:

- what object/response?

- what expected hit ratio?

- what is the perf goal? (latency? DB load? tail reduction?)

Declare freshness and correctness constraints

- can it be stale?

- for how long?

- can it be shared across users/tenants?

- what happens if it’s wrong?

Prove the cache key matches variability

List dimensions:

- identity

- permissions/version

- locale/representation

- query params

- API version

Choose the caching layer intentionally

- browser?

- CDN?

- in-memory?

- Redis?

- combination?

Add stampede protection by default

- single-flight

- soft TTL / stale-while-revalidate

- jitter

Add observability before shipping

- hit/miss metrics

- latency breakdown

- alerts for miss storms

FAQ

Sometimes, but be explicit about ownership.

Caching “rows” often turns Redis into a shadow database with different consistency rules. Prefer caching responses or computed views that are safe to recompute, and use versioned keys or bounded TTLs to avoid “hidden truth” living in cache.

Yes — for public, idempotent GETs with explicit cache-control rules and correct variation (“Vary”).

For authenticated or personalized APIs, treat CDN caching as opt-in: use “private” semantics or avoid shared caching unless you can prove it’s safe.

Content-hashed static assets + a CDN.

It’s the biggest performance gain with the lowest correctness risk, and it reduces load everywhere (browser, edge, backend).

Because you’ve introduced state that is:

- time-dependent (TTL)

- load-dependent (stampedes)

- deployment-dependent (warm vs cold)

- topology-dependent (which node or edge served you)

This is why cache observability and bounded staleness are not “nice to have.” They make the system debuggable.

Resources

What’s Next

Caching is the performance layer.

Now we move into the reliability layer — where asynchrony becomes unavoidable:

- background work

- retries

- at-least-once delivery

- “did we do this twice?”

Next month:

Queues, Retries, and Idempotency: Engineering Reality in Async Systems

Because the moment you add retries, caching’s cousin shows up:

The system will do things more than once — unless you design it not to.

Queues, Retries, and Idempotency: Engineering Reality in Async Systems

Async work is where production gets honest. This month is a practical playbook for queues, retries, idempotency keys, and the patterns that keep “background jobs” from duplicating money or burning trust.

Data Stores 101 for Architects: SQL, NoSQL, and the Shape of Consistency

Stop choosing databases by brand. Choose them by invariants, access patterns, and what “correct” means when the network is on fire.